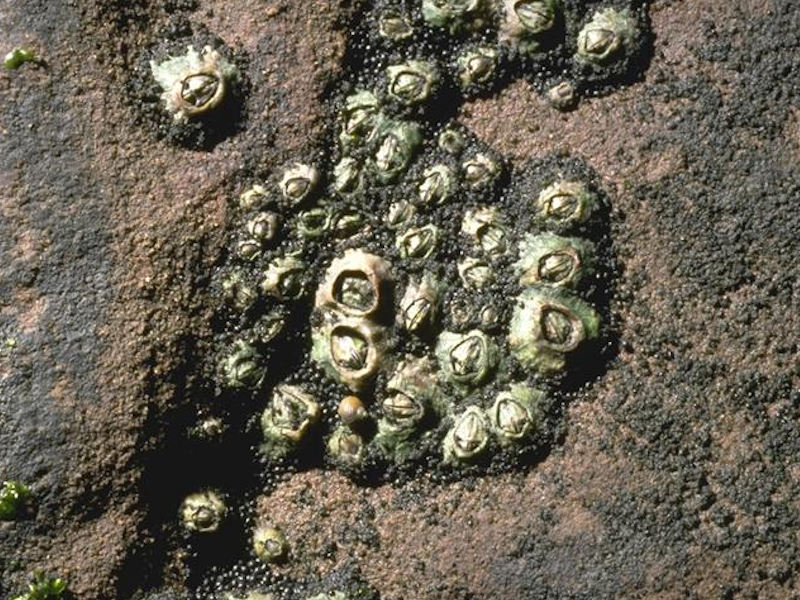

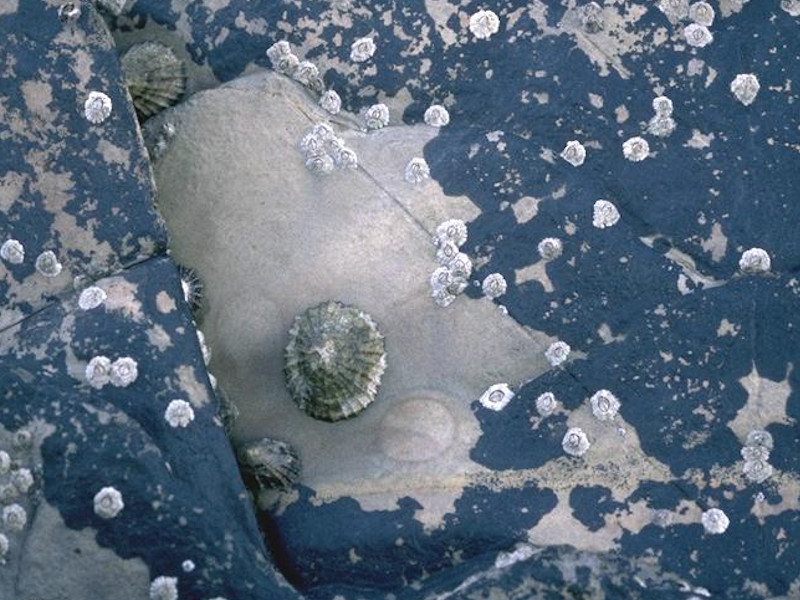

Verrucaria maura and sparse barnacles on exposed littoral fringe rock

| Researched by | Dr Harvey Tyler-Walters | Refereed by | This information is not refereed |

|---|

Summary

UK and Ireland classification

Description

This biotope (Ver.B) is usually found on more exposed coasts below the Verrucaria maura biotope Ver.Ver. It is found above the mussel Mytilus edulis and barnacles biotope (MytB) or above the barnacle and Patella spp. zone (Cht.Cht; Sem). Ver.B also occurs on vertical faces of moderately exposed shores where the Pelvetia canaliculata biotope (PelB) usually dominates on non-vertical faces. The abundance of Porphyra umbilicalis shows considerable seasonal and geographical variation. During warm weather Porphyra umbilicalis is often bleached light brown and sticks to the rock as it dries out. On southern shores it may be absent during the summer on all but the most exposed shores, as it dies back leaving the barnacle and lichen dominated community. In the cooler north the Porphyra umbilicalis covering persists throughout the year. Porphyra linearis can also be found in the among the Porphyra umbilicalis during the late winter and spring. (Information adapted from Connor et al., 2004; JNCC, 2015).

Depth range

Upper shoreAdditional information

-

Listed By

Sensitivity review

Sensitivity characteristics of the habitat and relevant characteristic species

The biotope LR.FLR.Lic.Ver and its sub-biotopes LR.FLR.Lic.Ver.Ver and LR.FLR. Lic.Ver.B are characterized by the abundance of the black lichen Verrucaria maura. A significant reduction in the abundance of Verrucaria maura, or its loss, would result in loss of the biotopes. Littorina saxatilis is also a characterizing species but it is mobile, not dependent on Verrucaria maura for habitat, and common in the upper to lower littoral fringe, the upper eulittoral and upper shore rockpools and crevices. If Littorina saxatilis was removed it would probably return quickly. Similarly, many of the macroalgae that occur are transient or opportunistic (e.g. Porphyra spp., Ulva spp.) and the gastropod fauna are mobile (e.g. Patella) or restricted to crevices (e.g. Melarhaphe neritoides). Kronberg (1988) recorded numerous species from the littoral 'black' zone in Europe but noted that the communities were generally species-poor and that most species were mobile, feeding in the 'black' zone temporally, before returning to the more marine or terrestrial regions of origin or to refuges in crevices. Therefore, Verrucaria maura is the only species required to recognize the biotopes (Ver and Ver.Ver). However, the barnacles (Semibalanus balanoides and/or Chthamalus montagui) that characterize Ver.B reach their upper shore limit in Ver.B and are probably more sensitive to change in this biotope than in barnacle dominant biotopes. If the barnacles were removed or lost then the Ver.B biotope would be replaced by Ver or Ver.Ver and the Ver.B biotope would be lost based on the habitat classification. Therefore, the sensitivity of the Ver.B biotope is based on the sensitivity of Verrucaria maura and the resident barnacles (Semibalanus balanoides and/or Chthamalus montagui).

Resilience and recovery rates of habitat

Sexual spores and asexual propagules of lichens are probably widely dispersed by the wind and mobile invertebrates while the microalgal symbionts are probably ubiquitous. Lichen growth rates are low, rarely more than 0.5-1 mm/year in crustose species while foliose species may grow up to 2-5 mm/year. For example, crustose lichens were reported to show radial increases of 0.1 mm/month while foliose species grow at 0.4-0.7 mm/month (Fletcher, 1980); Lichina pygmaea was reported to grow 3-6 cm/year at one site but only 0.5 mm/year at others (Fletcher, 1980). Dethier & Steneck (2001) recorded a maximum growth rate of 2 mm/year for Verrucaria mucosa in the laboratory. However, lichen growth rates varied widely between different locations, between different species and even between different thalli of the same species at the same site (Fletcher, 1980; Sancho et al., 2007). Cullinane et al. (1975) noted that many of the lichens lost due to an oil spill in Bantry Bay were probably 20-50 years old, based on their size, and lifespans of lichens have been estimated to be 100 years or more (Jones et al., 1974) and possibly up to 7000 years in the Antarctic (Sancho et al., 2007). However, lichen growth rates vary widely and many but not all lichens of extreme climates have slow growth rates. The highest growth rates are recorded in moist coastal-influenced regions, and lichens from temperature, tropical or sub-tropical areas may grow between a few millimetres to a few centimetres per year (Honeggar, 2008). Honeggar (2008) suggested that longevity in lichens required critical interpretation.

Fletcher (1980) suggested that newly exposed substratum needs to be modified by weathering and that initiation of the new thallus is thought to take several years. Rolan & Gallagher (1991) reported that Verrucaria spp. populations were destroyed on the upper shore, 'cleaned' by bulldozing at one site in Sullom voe after the Esso Bernica oil spill in 1978. At another site, Verrucaria maura was recorded on loose rocks in the littoral, rocks that were presumed to be displaced from the upper shore. Rolan & Gallagher (1991) also reported that lichens recovered within a year or two at four cleared sites, but did not specify the lichen species in question or whether they were littoral or supralittoral species. Crump & Moore (1997) observed that lichens had not colonized experimentally cleared substrata within 12 months. Moore (2006) reported that areas of bare rock (left after rock slices were removed by high-pressure water cleaning) showed no signs of recruitment by Verrucaria maura until 6 years after the Sea Empress oil spill, and that new colonies had grown to 2 mm in diameter 3 years later (9 years after the spill), and provided 'appreciable cover'.

The lifespan of Chthamalus spp. is 10+ years (Mieszkowska et al., 2014). Sexual maturity can be reached in the first year and a number of broods may be produced each year. Burrows et al. (1992) found that the number of eggs per brood of Chthamalus stellatus ranged between 1,274 - 3,391 in Britain, depending on body size and weight. Shore height affects a number of life history parameters. Growth is more rapid and the mortality rate is greater lower down on the shore (Southward & Crisp, 1950). Towards the northern limits of distribution annual recruitment is low (Kendall & Bedford, 1987) and they have an increased longevity (Lewis, 1964). Burrows et al. (1992) found that the fecundity generally increased with lower shore levels colonized, with estimates of 1-2 broods per year at high shore levels, 2 to over three at mid shore levels and over 2 to over 4 at low shore levels. Southward (1978) suggested that Chthamalus montagui breeds one to two months later than Chthamalus stellatus. However, Crisp et al. (1981) found little difference in SW Britain, with the main breeding peak in June and August (O'Riordan et al., 1995). Throughout the breeding season, most individuals produce several broods (Burrows et al., 1992; O'Riordan et al., 1992), with a small percentage of the population remaining reproductively active throughout the year (O'Riordan et al., 1995; Barnes, 1989).

On rocky shores, barnacles are often quick to colonize available gaps. Bennell (1981) observed that barnacles that were removed when the surface rock was scraped off in a barge accident at Amlwch, North Wales returned to pre-accident levels within 3 years. Petraitis & Dudgeon (2005) also found that Semibalanus balanoides quickly recruited (present a year after and increasing in density) to experimentally cleared areas within the Gulf of Maine, which had previously been dominated by Ascophyllum nodosum. However, barnacle densities were fairly low (on average 7.6% cover) and predation levels in smaller patches were high (Petraitis et al., 2003). Local environmental conditions, including surface roughness (Hills & Thomason, 1998), wind direction (Barnes, 1956), shore height, wave exposure (Bertness et al., 1991) and tidal currents (Leonard et al., 1998) have been identified, among other factors, as factors affecting settlement of Semibalanus balanoides. Biological factors such as larval supply, competition for space, the presence of adult barnacles (Prendergast et al., 2009) and the presence of species that facilitate or inhibit settlement (Kendall et al., 1985, Jenkins et al., 1999) also play a role in recruitment. Mortality of juveniles can be high but highly variable, with up to 90% of Semibalanus balanoides dying within ten days (Kendall et al., 1985). Presumably, these factors would also influence the transport, supply and settlement of Chthamaus spp. larvae.Resilience assessment. Mobile invertebrate fauna and opportunistic macroalgae will probably recolonize rapidly. The above evidence suggests that barnacles would recover within a few years. Their abundance in this biotope is only occasional (ca <10%) so that a single recruitment event may be enough to repopulate the habitat. Hence, the resilience of barnacles in this biotope is probably 'High' even if removed or lost (resistance is 'Low' or Very low'). Little information on recovery in Verrucaria maura was found, although if similar to Verrucaria mucosa (a maximum of 2 mm/year), growth is slow. Evidence from Moore (2006) suggests that Verrucaria maura can recolonize bare rock within 6 years and develop 'appreciable' cover within 9 years. Where the cover of Verrucaria maura is reduced or damaged regrowth is likely, but recovery is likely to take between 2 and 10 years depending on location and assuming growth rates vary. Similarly, it may colonize and reach 'appreciable cover' on bare rock within 10 years. Therefore, the resilience of the biotope as a whole would be assessed as 'Medium'. However, although the Ver.B. biotope is characterized by Verrucaria maura cover and bare rock, Ver and Ver.Ver are characterized by almost complete cover.

Hydrological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Temperature increase (local) [Show more]Temperature increase (local)Benchmark. A 5°C increase in temperature for one month, or 2°C for one year. Further detail EvidenceMarine lichens are exposed to extremes of temperature from hot, dry summers to cold, frosty winters. Fletcher (1980) noted that few studies implicated high or low temperatures as a factor affecting seashore lichens, but that changes in temperature affect water relations. Increased temperature may increase desiccation (see emergence) although, other factors are involved, such as wind and wave action, precipitation, sunlight and shading. Fletcher (1980) suggested that the effect of temperature on littoral lichens was inconclusive. For example, Verrucaria maura is abundant on both sunny and shaded shores but is considered a shade tolerant plant from North Africa to France and in Scandinavia. Reid (1969; cited in Fletcher, 1980) reported that Verrucaria mucosa had the similar temperature resistance to the algae with which it is ecologically associated but that Verrucaria maura was even less resistant. However, Fletcher (1980) also suggested that temperature was an important factor for water conservation, in combination with insolation, shade and wind, emersion and precipitation. This biotope may contain a mix of Chthamalus and Semibalanus balanoides barnacles depending on location. Increased temperatures are likely to favour chthamalid barnacles (that dominate the south and south-west examples of this biotope) rather than Semibalanus balanoides (that dominates northern and eastern examples of this biotope) (Southward et al. 1995; Connor et al., 2004). Long-term time series show that successful recruitment of Semibalanus balanoides is correlated to sea temperatures (Mieszkowska et al., 2014) and that, due to recent warming, its range has been contracting northwards. Temperatures above 10 to 12°C inhibit reproduction (Barnes, 1957, 1963, Crisp & Patel, 1969) and laboratory studies suggest that temperatures at or below 10°C for 4-6 weeks are required in winter for reproduction, although the precise threshold temperatures for reproduction are not clear (Rognstad et al., 2014). Observations of recruitment success in Semibalanus balanoides throughout the south-west of England, strongly support the hypothesis that an extended period (4-6 weeks) of sea temperatures <10°C is required to ensure a good supply of larvae (Rognstad et al., 2014, Jenkins et al., 2000). During periods of high reproductive success, linked to cooler temperatures, the range of barnacles has been observed to increase, with range extensions in the order of 25 km (Wethey et al., 2011) and 100 km (Rognstad et al., 2014). Increased temperatures are likely to favour chthamalid barnacles rather than Semibalanus balanoides (Southward et al., 1995). Chthamalus montagui and Chthamalus stellatus are warm water species, with a northern limit of distribution in Britain so are likely to be tolerant of long-term increases in temperature. The range of Chthamalus stellatus and Chthamalus montagui has been extending northwards due to increasing temperatures. Breeding of Chthamalus stellatus in France occurs in April (Barnes, 1992), and correlates with mean air and sea temperatures of 11 - 12°C, and maximum temperatures of 14 °C. Barnes (1992) found that at an upper-temperature limit of 20 - 21°C in the sea and 24 - 25°C in the air reproductive activity decreased. Chthamalus suffers a failure of fertilization at temperatures of 9°C and below (Patel & Crisp, 1960), its lower critical temperature for feeding activity is 4.6°C (Southward, 1955). Semibalanus balanoides out-competes Chthamalus species for space, but recruitment declines and failures of Semibalanus balanoides in response to warmer temperatures benefit Chthamalus species by allowing them to persist and recruit (Mieszkowska et al., 2014). Sensitivity assessment. The 'black lichen zone' (Ver) experiences the extremes of hot summers and cold frosty winters and is, therefore, adapted to extreme variation in temperature. It also occurs from North Africa to Scandinavia, so that it is unlikely to be adversely affected by changes in temperature at the benchmark level within Britain and Ireland. Similarly, chronic or acute change at the benchmark level may affect reproduction and survival or the difference barnacle species and affect the relative abundance of Semibalanus or Chthamalus. However, the biotope will remain as long as one of the characteristic barnacle species remains. Therefore, a resistance of High is suggested. Resilience is, therefore, likely to be High, and the biotope has been assessed as Not sensitive at the benchmark level. Ellis et al. (2007) modelled the effect of climate change scenarios on selected terrestrial lichens and identified potential threats to Northern montane and Boreal species, and uncertainties in the fate of species typical of the Atlantic coast margin, but no information on littoral species was found. Similarly, longer-term, broad-scale perturbations such as increased temperatures from climate change might have a greater effect on the relative abundance of the characteristic barnacles. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Temperature decrease (local) [Show more]Temperature decrease (local)Benchmark. A 5°C decrease in temperature for one month, or 2°C for one year. Further detail EvidenceMarine lichens are exposed to extremes of temperature from hot, dry summers to cold, frosty winters. Fletcher (1980) noted that few studies implicated high or low temperatures as a factor affecting seashore lichens, but that changes in temperature affect water relations. Increased temperature may increase desiccation (see emergence) although, other factors are involved, such as wind and wave action, precipitation, sunlight and shading. Fletcher (1980) suggested that the effect of temperature on littoral lichens was inconclusive. For example, Verrucaria maura is abundant on both sunny and shaded shores but is considered a shade tolerant plant from North Africa to France and in Scandinavia. Reid (1969; cited in Fletcher, 1980) reported that Verrucaria mucosa had the similar temperature resistance to the algae with which it is ecologically associated but that Verrucaria maura was even less resistant. However, Fletcher (1980) also suggested that temperature was an important factor for water conservation, in combination with insolation, shade and wind, emersion and precipitation. This biotope may contain a mix of Chthamalus and Semibalanus balanoides barnacles depending on location. Decreased temperatures are likely to favour Semibalanus balanoides (that dominates northern and eastern examples of this biotope) rather than chthamalid barnacles (that dominate the south and south-west examples of this biotope) (Southward et al. 1995; Connor et al., 2004). Long-term time series show that successful recruitment of Semibalanus balanoides is correlated to sea temperatures (Mieszkowska et al., 2014) and that, due to recent warming, its range has been contracting northwards. Temperatures above 10 to 12°C inhibit reproduction (Barnes, 1957, 1963, Crisp & Patel, 1969) and laboratory studies suggest that temperatures at or below 10°C for 4-6 weeks are required in winter for reproduction, although the precise threshold temperatures for reproduction are not clear (Rognstad et al., 2014). Observations of recruitment success in Semibalanus balanoides throughout the south-west of England, strongly support the hypothesis that an extended period (4-6 weeks) of sea temperatures <10°C is required to ensure a good supply of larvae (Rognstad et al., 2014, Jenkins et al., 2000). During periods of high reproductive success, linked to cooler temperatures, the range of barnacles has been observed to increase, with range extensions in the order of 25 km (Wethey et al., 2011), and 100 km (Rognstad et al., 2014). The barnacle Semibalanus balanoides has a greater tolerance for cooler temperatures and a decrease in temperature may enhance recruitment success and replacement of Chthamalus spp. The tolerance of Semibalanus balanoides collected in the winter (and thus acclimated to lower temperatures) to low temperatures was tested in the laboratory. The median lower lethal temperature tolerance was -14.6°C (Davenport & Davenport, 2005). Chthamalus montagui and Chthamalus stellatus are warm water species, with a northern limit of distribution in Britain so are likely to be tolerant of long-term increases in temperature. The range of Chthamalus stellatus and Chthamalus montagui has been extending northwards due to increasing temperatures. Breeding of Chthamalus stellatus in France occurs in April (Barnes, 1992), and correlates with mean air and sea temperatures of 11 - 12°C, and maximum temperatures of 14°C. Barnes (1992) found that at an upper-temperature limit of 20 - 21°C in the sea and 24 - 25°C in the air reproductive activity decreased. Chthamalus suffers a failure of fertilization at temperatures of 9°C and below (Patel & Crisp, 1960), its lower critical temperature for feeding activity is 4.6°C (Southward, 1955). The cold winter of 2009-10 in France led to recruitment failure in Chthamalus species (Wethey et al., 2011). Semibalanus balanoides out-competes Chthamalus species for space, but recruitment declines and failures of Semibalanus balanoides in response to warmer temperatures benefit Chthamalus species by allowing them to persist and recruit (Mieszkowska et al., 2014). Sensitivity assessment. The 'black lichen zone' (Ver) experiences the extremes of hot summers and cold frosty winters and is, therefore, adapted to extreme variation in temperature. It also occurs from North Africa to Scandinavia, so that it is unlikely to be adversely affected by changes in temperature at the benchmark level within Britain and Ireland. Similarly, chronic or acute change at the benchmark level may affect reproduction and survival or the difference barnacle species and affect the relative abundance of Semibalanus or Chthamalus. However, the biotope will remain as long as one of the characteristic barnacle species remains. Therefore, a resistance of High is suggested. Resilience is, therefore, likely to be High, and the biotope has been assessed as Not sensitive at the benchmark level. Ellis et al. (2007) modelled the effect of climate change scenarios on selected terrestrial lichens and identified potential threats to Northern montane and Boreal species, and uncertainties in the fate of species typical of the Atlantic coast margin, but no information on littoral species was found. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Salinity increase (local) [Show more]Salinity increase (local)Benchmark. A increase in one MNCR salinity category above the usual range of the biotope or habitat. Further detail EvidenceThe littoral fringe is likely to experience localised evaporation and a resultant increase in surface salinity during neap and low tides in hot summers and/or warm windy conditions. Fletcher (1980) noted that marine lichens in the lower littoral fringe died out in waters less than 20‰ while upper littoral fringe lichens were found in waters of 4-20‰ salinity. However, Fletcher (1980) commented that loss of littoral lichens in estuaries can also be attributed to changes in pH, silt, reduced tidal range, and reduced wave exposure. Barnes & Barnes (1974) found that larvae from six barnacle species including Chthamalus stellatus and Semibalanus (as Balanus) balanoides, completed their development to nauplii larvae at salinities between 20-40% and some embryos exposed at later development stages could survive at higher and lower salinities. Overall, littoral lichens receive regular inundation by seawater, unlike the supralittoral, and may not experience the extremes of salt spray. Nevertheless, there is not enough evidence to assess the sensitivity of the biotope to hypersaline conditions. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Salinity decrease (local) [Show more]Salinity decrease (local)Benchmark. A decrease in one MNCR salinity category above the usual range of the biotope or habitat. Further detail EvidenceThe littoral fringe is likely to experience localised evaporation and a resultant increase in surface salinity during neap and low tides in hot summers and/or warm windy conditions. Conversely, it is exposed to rainfall and freshwater runoff during low and neap tides. Fletcher (1980) noted that marine lichens in the lower littoral fringe died out in waters less than 20‰ while upper littoral fringe lichens were found in waters of 4-20‰ salinity. However, Fletcher (1980) commented that loss of littoral lichens in estuaries can also be attributed to changes in pH, silt, reduced tidal range, and reduced wave exposure. Barnes & Barnes (1974) found that larvae from six barnacle species including Chthamalus stellatus and Semibalanus (as Balanus) balanoides, completed their development to nauplii larvae at salinities between 20-40% and some embryos exposed at later development stages could survive at higher and lower salinities. Barnes & Barnes (1965) found that in high suspended solids and low salinity there was a decrease in the number of eggs per brood of Chthamalus stellatus / Chthamalus montagui. If salinities decrease below 21 psu all cirral activity of barnacles normally associated with full salinity waters, ceases (Foster, 1971b). Semibalanus balanoides are tolerant of a wide range of salinity and can survive periodic emersion in freshwater, e.g. from rainfall or freshwater run-off, by closing their opercular valves (Foster, 1971b). They can also withstand large changes in salinity over moderately long periods of time by falling into a "salt sleep" and can be found on shores (example from Sweden) with large fluctuations in salinity around a mean of 24 (Jenkins et al., 2001). Sensitivity assessment. The characteristic barnacles are probably adapted to changes in salinity. Hence, a reduction from full to reduced salinity may result in some mortality (resistance is 'Medium), although recovery is probably rapid (resilience is 'High'). However, the limited evidence suggests that littoral lichens would be adversely affected by a reduction of salinity and a resistance of 'Low' is suggested but at 'Low' confidence. Resilience is probably 'Medium', therefore, a sensitivity of 'Medium' is recorded.

| LowHelp | MediumHelp | MediumHelp |

Water flow (tidal current) changes (local) [Show more]Water flow (tidal current) changes (local)Benchmark. A change in peak mean spring bed flow velocity of between 0.1 m/s to 0.2 m/s for more than one year. Further detail EvidenceThe littoral fringe is unlikely to be affected by changes in water flow as described in the pressure benchmark. Runoff due to heavy rainfall is possible but is outside the scope of the pressure. Therefore, the pressure is Not relevant. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Emergence regime changes [Show more]Emergence regime changesBenchmark. 1) A change in the time covered or not covered by the sea for a period of ≥1 year or 2) an increase in relative sea level or decrease in high water level for ≥1 year. Further detail EvidenceThe emergence regime, that is the time covered or uncovered by the tide, is likely to change the frequency of drying and wetting of lichens, especially on sheltered shores. Fletcher (1980) noted that littoral lichens are emersed for several weeks during neap tides, during which time they are exposed to the hottest and dryest periods in summer and the coldest and most frost-prone periods in winter. The levels of moisture and relative duration of wet and dry periods are the most important factors controlling vertical zonation in marine lichens. Rates of evaporation and hence desiccation is dependent on the slope and drainage of the shore, the rock type and its porosity, temperature and hence insolation and aspect, and wind exposure. Any activity that changes the exposure of the shore to wind, wave, rain or sunlight is likely to affect littoral lichen communities.

Some regional variation occurs in the distribution of Chthamalus on the shore and its vertical zonation will be affected by wave splash and shore steepness. On shores in west Scotland, Chthamalus stellatus and Chthamalus montagui are restricted to high shores as Semibalanus balanoides, the northern species, is competitively superior at these latitudes (Connell, 1961a,b). Further south in the UK, the two genera coexist in the mid-shore (Crisp et al., 1981). Increased emergence would reduce the feeding time for attached suspension feeders within the biotope and the increased desiccation. It is likely that the distribution of Chthamalus stellatus will move further up the shore, with no noticeable difference in the range. Chthamalus stellatus / Chthamalus montagui are very tolerant of high periods of emersion, yet Patel & Crisp (1960) found that when barnacles which were brooding eggs were kept out of the water, a second batch of eggs was not produced. Decreased emergence is likely to lead to the habitat the biotope is found in becoming more suitable for the lower shore species generally found below the biotope, leading to replacement. Adults of Chthamalus stellatus can survive permanent submersion (Barnes, 1953). However, competition between Semibalanus balanoides is likely to play an important role in the changes in species distribution. Semibalanus balanoides is less tolerant of desiccation stress than Chthamalus barnacles species but is considered to out-compete Chthamalus spp. in the mid and lower shore. Sensitivity assessment. Water relations (Fletcher 1980) are vital to the zonation of marine lichens and the 'black lichen belt' exists in a distinct balance between immersion and emersion. A decrease in emersion (increased inundation) would probably allow the 'black lichen belt' to extend up the shore (where suitable substratum exists) and replace supralittoral lichens at the bottom of the supralittoral. However, the lower littoral fringe would probably be lost to competition from macroalgae or barnacles, depending on the exposure of the shore, and the abundance of the characteristic barnacles would probably increase. Conversely, an increase in emersion (reduced inundation) would probably result in loss of the upper limit of the Verrucaria maura belt and its replacement by supralittoral lichens typical of the yellow-orange belt (e.g. Caloplaca spp.). Therefore, a decrease in emersion is likely to result is a slow shift in the biotope up the shore but an increase in emergence is likely to result in a rapid loss of Verrucaria spp. at its upper limit, based on observations by Fletcher (1976; cited in Fletcher, 1980). Hence, a resistance of 'Low' is suggested. As resilience is probably 'Medium', a sensitivity of 'Medium' is recorded. | LowHelp | MediumHelp | MediumHelp |

Wave exposure changes (local) [Show more]Wave exposure changes (local)Benchmark. A change in near shore significant wave height of >3% but <5% for more than one year. Further detail EvidenceLR.FLR.Lic.Ver and Ver.Ver are recorded from very wave exposed to very wave sheltered conditions while Ver.B is only recorded from wave exposed conditions (Connor et al., 2004). The 'black lichen band' tends to be wider in more wave exposed conditions, as the influence of wave action and splash are carried further up the shore. Therefore, changes in wave exposure may either increase or decrease the width of the 'black lichen band' depending on the nature of the shore. The extent of the band (especially Ver.B.) may extend on sheltered shore exposed to increased wave action but be reduced on wave exposed shores where the wave action is reduced, which suggests a Low resistance to change. Ver.B may be particularly sensitive to reduced wave exposure as it is only recorded from wave exposed shores. However, a change in significant wave height of 3-5% (the benchmark) is probably not significant on wave exposed shores, and might only be of minor benefit in the long-term on very sheltered shores. Therefore, a resistance of High is recorded, so that, a resilience of High and sensitivity of Not sensitive are recorded at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Chemical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Transition elements & organo-metal contamination [Show more]Transition elements & organo-metal contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceLichens are known indicators of heavy metals in the environment, especially iron (Seaward, 2008). Seashore lichens often indicate environmental concentrations of heavy metals or accumulate them, frequently to very high levels (Fletcher, 1980). The accumulation of high levels of heavy metals may deter grazers (Gerson & Seaward, 1977). For example, Verrucaria maura was reported to accumulate Fe to 2.5 million times over the concentration in seawater, and Zn by a factor of 8000. Some species accumulate lead (Pb) to 100 ppm and cadmium (Cd) to 2 ppm of thallus dry weight (Fletcher, 1980). Heavy metals may be derived from rainfall, and dust as well as seawater (Fletcher, 1980). Gerson & Seaward (1977) noted that accumulated heavy metals could potentially accumulate up lichen-based food webs, e.g. the lichen to caribou to man food chain in Alaska. However, no information on bioaccumulation through littoral lichen communities was found. Overall, the ability of lichens to accumulate heavy metals to such high levels suggests a 'High' resistance to the heavy metal ions studied. Therefore, the lichen community is probably 'Not sensitive to heavy metal contamination. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Hydrocarbon & PAH contamination [Show more]Hydrocarbon & PAH contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed but evidence is presented where available. Several studies have documented the effects of oil spills on marine lichen communities, although in many cases is difficult to separate the effects of oiling from the effects of dispersants.

| Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Synthetic compound contamination [Show more]Synthetic compound contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed but evidence is presented where available. Several studies have documented the effects of oil spills on supralittoral lichen communities, although in many cases is difficult to separate the effects of oiling from the effects of dispersants. Most studies concluded that the decontamination methods, (including dispersants) were more toxic to lichens than the oil itself (see Hydrocarbon and PAH contamination above).

| Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Radionuclide contamination [Show more]Radionuclide contaminationBenchmark. An increase in 10µGy/h above background levels. Further detail EvidenceLichens have also been reported to accumulate radionuclides in a similar manner to other heavy metals (see above) (Gerson & Seaward, 1977; Fletcher, 1980). Radionuclides could potentially accumulate up food webs based on lichen species, however, no further evidence was found. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Introduction of other substances [Show more]Introduction of other substancesBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

De-oxygenation [Show more]De-oxygenationBenchmark. Exposure to dissolved oxygen concentration of less than or equal to 2 mg/l for one week (a change from WFD poor status to bad status). Further detail EvidenceThe littoral fringe is rarely inundated and is often exposed to the air. For example, Fletcher (1980) noted that Lichina confinis, a species that occurs at the top of the littoral fringe, spent a maximum of 1% of time submerged each year while Verrucaria striatula, a species that occurs in the lower littoral fringe below the Verrucaria maura, spent a maximum of 44% of time submerged each year. Therefore, the 'black lichen belt' characterized by Ver.Ver and Ver.B are exposed to the air for the majority of the time. Even if the water lapping over the littoral fringe was deoxygenated, wave action and turbulent flow over the rock surface would probably aerate the water column. Hence, the biotope is unlikely to be exposed to deoxygenated conditions and 'Not relevant' is recorded. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Nutrient enrichment [Show more]Nutrient enrichmentBenchmark. Compliance with WFD criteria for good status. Further detail EvidenceNutrient levels are a determining factor in supralittoral lichen zonation (Fletcher, 1980) but the evidence of the importance of nutrient in the in the littoral fringe is less clear. Wootton (1991) examined the effects of bird guano on rocky shore lichens in the San Juan archipelago, Washington. Verrucaria mucosa cover declined in areas affected by guano but the decline was only significant in wave exposed sites where the cover of Prasiola meridionalis increased. Connor et al. (2004) noted that Prasiola and opportunistic algae (e.g. Ulva and Porphyra) grow over the Verrucaria belt. However, no evidence on the effects on Verrucaria maura was found. Holt et al. (1995) suggested that smothering of barnacles by ephemeral green algae is a possibility under eutrophic conditions. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Organic enrichment [Show more]Organic enrichmentBenchmark. A deposit of 100 gC/m2/yr. Further detail EvidenceNutrient levels are a determining factor in supralittoral lichen zonation (Fletcher, 1980) but the evidence of the importance of nutrient in the in the littoral fringe is less clear. Wootton (1991) examined the effects of bird guano on rocky shore lichens in the San Juan archipelago, Washington. Verrucaria mucosa cover declined in areas affected by guano but was only significant in wave exposed sites where the cover of Prasiola meridionalis increased. Guano provides nitrates, phosphates, potassium and some salts (Wootton, 1991) but may introduce some organic material. In addition, organic-rich runoff, e.g. from agriculture and livestock, could introduce organic carbon to the littoral fringe. Organic-rich runoff would probably result in Prasiola growth over the 'black lichen belt', where wave exposure allowed. However, no direct evidence on the effects of organic enrichment in the littoral fringe was found and not sensitivity assessment was made. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Physical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Physical loss (to land or freshwater habitat) [Show more]Physical loss (to land or freshwater habitat)Benchmark. A permanent loss of existing saline habitat within the site. Further detail EvidenceAll marine habitats and benthic species are considered to have a resistance of ‘None’ to this pressure and to be unable to recover from a permanent loss of habitat (resilience is ‘Very low’). Sensitivity within the direct spatial footprint of this pressure is, therefore ‘High’. Although no specific evidence is described confidence in this assessment is ‘High’, due to the incontrovertible nature of this pressure. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical change (to another seabed type) [Show more]Physical change (to another seabed type)Benchmark. Permanent change from sedimentary or soft rock substrata to hard rock or artificial substrata or vice-versa. Further detail EvidenceThe lichen community typical of this biotope is only found on hard substrata and dominates rocks in the littoral fringe. A change to a sedimentary substratum, however unlikely, would result in the permanent loss of the biotope. Therefore, the biotope has a resistance of 'None', with a 'Very low' resilience (as the effect is permanent) and, therefore, a sensitivity of 'High'. Although no specific evidence is described confidence in this assessment is ‘High’, due to the incontrovertible nature of this pressure. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical change (to another sediment type) [Show more]Physical change (to another sediment type)Benchmark. Permanent change in one Folk class (based on UK SeaMap simplified classification). Further detail EvidenceNot Relevant on hard rock biotopes. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Habitat structure changes - removal of substratum (extraction) [Show more]Habitat structure changes - removal of substratum (extraction)Benchmark. The extraction of substratum to 30 cm (where substratum includes sediments and soft rock but excludes hard bedrock). Further detail EvidenceNot Relevant on hard rock biotopes. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Abrasion / disturbance of the surface of the substratum or seabed [Show more]Abrasion / disturbance of the surface of the substratum or seabedBenchmark. Damage to surface features (e.g. species and physical structures within the habitat). Further detail EvidenceFletcher (1980) reported that the species diversity of lichens decreased in areas subject to mechanical damage, such as trampling, the passage of boats or vehicles, mining or physical removal due to building works. In disturbed areas, the 'normal' lichen flora is replaced by disturbance tolerant species, typically faster-growing species. For example, the littoral zone is dominated by Arthopyrenia halodytes in disturbed areas (Fletcher, 1980). Dethier (1994) noted that Verrucaria mucosa was less susceptible to experimental brushing with 'steel brush' than other crustose species in the littoral, but that it became more susceptible to damage from a steel and a nylon brush when completely submerged. However, no information on Verrucaria maura was found. Verucaria maura was not killed by high pressure washing during the Sea Empress oil spill cleanup (Moore, 2006) but was removed by bulldozing of the shore after the Esso Bernica oil spill (Rolan & Gallagher, 1991), although it was removed because the surface of the rock itself was removed or damaged. The effects of trampling on barnacles appear to be variable with some studies not detecting significant differences between trampled and controlled areas (Tyler-Walters & Arnold, 2008). However, this variability may be related to differences in trampling intensities and abundance of populations studied. The worst case incidence was reported by Brosnan & Crumrine (1994) who reported that a trampling pressure of 250 steps in a 20x20 cm plot one day a month for a period of a year significantly reduced barnacle cover at two study sites. Barnacle cover reduced from 66% to 7% cover in 4 months at one site and from 21% to 5% within 6 months at the second site. Overall barnacles were crushed and removed by trampling. Barnacle cover remained low until recruitment the following spring. Long et al. (2011) also found that heavy trampling (70 humans km-1 shoreline h-1) led to reductions in barnacle cover. Single step experiments provide a clearer, quantitative indication of sensitivity to direct abrasion. Povey & Keough (1991) in experiments on shores in Mornington Peninsula, Victora, Australia, found that in single step experiments 10 out of 67 barnacles, (Chthamalus antennatus about 3mm long), were crushed. However, on the same shore, the authors found that limpets may be relatively more resistant to abrasion from trampling. Following step and kicking experiments, few individuals of the limpet Cellana trasomerica, (similar size to Patella vulgata) suffered damage or relocated (Povey & Keough, 1991). One kicked limpet (out of 80) was broken and 2 (out of 80) limpets that were stepped on could not be relocated the following day (Povey & Keough, 1991). Trampling may lead to indirect effects on limpet populations, Bertocci et al. (2011) found that the effects of trampling on Patella sp. increased the temporal and spatial variability of in abundance. The experimental plots were sited on a wave-sheltered shore dominated by Ascophyllum nodosum. On these types of shore, trampling in small patches, that removes macroalgae and turfs, will indirectly enhance habitat suitability for limpets by creating patches of exposed rock for grazing. Shanks & Wright (1986) found that even small pebbles (<6 cm) that were thrown by wave action in Southern California shores could create patches in Chthamalus fissus aggregations and could smash owl limpets (Lottia gigantea). Average, estimated survivorship of limpets at a wave exposed site, with many loose cobbles and pebbles allowing greater levels of abrasion was 40% lower than at a sheltered site. Severe storms were observed to lead to the almost total destruction of local populations of limpets through abrasion by large rocks and boulders. Sensitivity assessment. There is little direct evidence on the effect of surface abrasion on the 'black lichen belt'. Verucaria maura is crustose and closely adherent to the rock surface so may resist abrasion and only be removed where the abrasion destroys the rock surface. However, the observation that fast growing lichen species come to dominate areas subject to disturbance (Fletcher, 1980) suggests that the 'black lichen belt' may be sensitive. Gastropods would probably be removed by abrasion and barnacle crushed, except where they occur in crevices. Overall, a resistance of Medium is suggested to represent localised damage of the rock surface or long-term disturbance but with 'Low' confidence. As resilience is probably Medium and sensitivity assessment of Medium is recorded. | MediumHelp | MediumHelp | MediumHelp |

Penetration or disturbance of the substratum subsurface [Show more]Penetration or disturbance of the substratum subsurfaceBenchmark. Damage to sub-surface features (e.g. species and physical structures within the habitat). Further detail EvidencePenetration is unlikely to be relevant to hard rock substrata. Therefore, the pressure is Not relevant. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Changes in suspended solids (water clarity) [Show more]Changes in suspended solids (water clarity)Benchmark. A change in one rank on the WFD (Water Framework Directive) scale e.g. from clear to intermediate for one year. Further detail EvidenceThe littoral fringe is rarely submerged and is often exposed to the air. For example, Fletcher (1980) noted that Lichina confinis, a species that occurs at the top of the littoral fringe, spent a maximum of 1% of time submerged each year while Verrucaria striatula, a species that occurs in the lower littoral fringe below the Verrucaria maura, spent a maximum of 44% of time submerged each year. Therefore, the 'black lichen belt' characterized by Ver.Ver and Ver.B are exposed to the air for the majority of the time. Hence, an increase in turbidity may not adversely affect the availability of light. Nevertheless, Fletcher (1980) noted that littoral fringe lichens die back in estuarine conditions but that loss of littoral lichens in estuaries can also be attributed to changes in salinity, pH, silt, reduced tidal range, or reduced wave exposure. Therefore, an increase in turbidity due to suspended solids (at the benchmark) may be detrimental to the characteristic Verrucaria maura and a resistance of 'Medium' is suggested but at Low confidence. As resilience is probably 'Medium', sensitivity is assessed as 'Medium' at the benchmark level. | MediumHelp | MediumHelp | MediumHelp |

Smothering and siltation rate changes (light) [Show more]Smothering and siltation rate changes (light)Benchmark. ‘Light’ deposition of up to 5 cm of fine material added to the seabed in a single discrete event. Further detail EvidenceNo evidence on the effect of siltation or smothering by sediment on littoral lichens was found. The lack of littoral lichens in estuaries was attributed to siltation amongst other factors by Fletcher (1980) but not to smothering alone. The barnacles that characterize this biotope are found permanently attached to hard substrata and are suspension feeders. They have no ability to escape from silty sediments that would bury individuals and prevent feeding and respiration. However, no direct evidence for sensitivity to siltation was found. Therefore, no sensitivity assessment was made. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Smothering and siltation rate changes (heavy) [Show more]Smothering and siltation rate changes (heavy)Benchmark. ‘Heavy’ deposition of up to 30 cm of fine material added to the seabed in a single discrete event. Further detail EvidenceNo evidence on the effect of siltation or smothering by sediment on littoral lichens was found. The lack of littoral lichens in estuaries was attributed to siltation amongst other factors by Fletcher (1980) but not to smothering alone. The barnacles that characterize this biotope are found permanently attached to hard substrata and are suspension feeders. They have no ability to escape from silty sediments that would bury individuals and prevent feeding and respiration. However, no direct evidence for sensitivity to siltation was found. Therefore, no sensitivity assessment was made. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Litter [Show more]LitterBenchmark. The introduction of man-made objects able to cause physical harm (surface, water column, seafloor or strandline). Further detail EvidenceNot assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Electromagnetic changes [Show more]Electromagnetic changesBenchmark. A local electric field of 1 V/m or a local magnetic field of 10 µT. Further detail EvidenceNo evidence was found. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Underwater noise changes [Show more]Underwater noise changesBenchmark. MSFD indicator levels (SEL or peak SPL) exceeded for 20% of days in a calendar year. Further detail EvidenceNot relevant | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Introduction of light or shading [Show more]Introduction of light or shadingBenchmark. A change in incident light via anthropogenic means. Further detail EvidenceVerrucaria maura is well developed on both shaded and sunny coasts in Britain and Ireland but is considered a shade plant in North Africa, France and Scandinavia (Fletcher, 1980). Verrucaria mucosa and green forms of Verrucaria striatula increase in abundance on shaded shores and may, therefore, increase in abundance in the 'black lichen belt'. Semibalanus balanoides sheltered from the sun grew bigger than unshaded individuals (Hatton, 1938; cited in Wethey, 1984), although the effect may be due to indirect cooling effects rather than shading. Barnacles are also frequently found under algal canopies suggesting that they are tolerant of shading. Light levels have also been demonstrated to influence a number of phases of the reproductive cycle in Semibalanus balanoides. In general, light inhibits aspects of the breeding cycle. Penis development is inhibited by light (Barnes & Stone, 1972) while Tighe-Ford (1967) showed that constant light inhibited gonad maturation and fertilization. Davenport & Crisp (unpublished data from Menai Bridge, Wales, cited from Davenport et al., 2005) found that experimental exposure to either constant darkness, or 6 h light: 18 h dark photoperiods induced autumn breeding in Semibalanus. They also confirmed that very low continuous light intensities (little more than starlight) inhibited breeding. Latitudinal variations in the timing of the onset of reproductive phases (egg mass hardening) have been linked to the length of darkness (night) experienced by individuals rather than temperature (Davenport et al., 2005). Changes in light levels associated with climate change (increased cloud cover) were considered to have the potential to alter the timing of reproduction (Davenport et al., 2005) and to shift the range limits of this species southward. However, it is not clear how these findings may reflect changes in light levels from artificial sources, and whether observable changes would occur at the barnacle population as a result. The artificial increase in light or shade may not adversely affect the littoral fringe, although seasonal opportunistic algae may be excluded and complete shade (darkness) may exclude even the lichens in the long-term. Therefore, resistance is probably 'High' albeit with 'Low' confidence, so that resilience is 'High' and the biotope is probably 'Not sensitive' at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Barrier to species movement [Show more]Barrier to species movementBenchmark. A permanent or temporary barrier to species movement over ≥50% of water body width or a 10% change in tidal excursion. Further detail EvidenceNot relevant | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Death or injury by collision [Show more]Death or injury by collisionBenchmark. Injury or mortality from collisions of biota with both static or moving structures due to 0.1% of tidal volume on an average tide, passing through an artificial structure. Further detail EvidenceThe pressure definition is not directly applicable to the littoral fringe so Not relevant has been recorded. Collision via ship groundings or terrestrial vehicles is possible but the effects are probably similar to those of abrasion above. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Visual disturbance [Show more]Visual disturbanceBenchmark. The daily duration of transient visual cues exceeds 10% of the period of site occupancy by the feature. Further detail EvidenceLichens have no visual receptors, and the visual acuity of barnalces is probably limited to detecting shading by predators, so the pressure is Not relevant. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Biological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Genetic modification & translocation of indigenous species [Show more]Genetic modification & translocation of indigenous speciesBenchmark. Translocation of indigenous species or the introduction of genetically modified or genetically different populations of indigenous species that may result in changes in the genetic structure of local populations, hybridization, or change in community structure. Further detail EvidenceNo evidence on the translocation, breeding or species hybridization in lichens or the characterizing barnacle species was found. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Introduction of microbial pathogens [Show more]Introduction of microbial pathogensBenchmark. The introduction of relevant microbial pathogens or metazoan disease vectors to an area where they are currently not present (e.g. Martelia refringens and Bonamia, Avian influenza virus, viral Haemorrhagic Septicaemia virus). Further detail EvidenceNo evidence on disease or pathogens mediated mortality in lichens was found. The characterizing barnacles and the limpet Patella vulgata are considered subject to persistent, low levels of infection by pathogens and parasites. For example, Patella vulgata has been reported to be infected by the protozoan Urceolaria patellae (Brouardel, 1948) at sites sheltered from extreme wave action in Orkney. Baxter (1984) found shells to be infested with two boring organisms, the polychaete Polydora ciliata and a siliceous sponge Cliona celata. Sensitivity assessment. Based on the characterizing species and the lack of evidence for widespread, high-level mortality due to microbial pathogens the biotope is considered to have 'High' resistance to this pressure and therefore 'High' resilience (by default), the biotope is therefore considered to be 'Not sensitive'. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Removal of target species [Show more]Removal of target speciesBenchmark. Removal of species targeted by fishery, shellfishery or harvesting at a commercial or recreational scale. Further detail EvidenceNo information concerning the use of marine lichens was found. Extraction of lichens will undoubtedly reduce their abundance but probably not the extent of the supralittoral zone. However, No evidence of targeted removal was found. Similarly, barnacles are not subject to targeted removal. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Removal of non-target species [Show more]Removal of non-target speciesBenchmark. Removal of features or incidental non-targeted catch (by-catch) through targeted fishery, shellfishery or harvesting at a commercial or recreational scale. Further detail EvidenceVerrucaria spp. are crustose lichens, thin and closely attached to the surface of hard rocks. Similarly, barnacles are closely adherent to the rock surface. It is unlikely that they would be removed accidentally by any fishery activity at a commercial or recreational scale. Physical removal from rock by abrasion, or by removal of pieces of rock could occur during oil spill cleanup by high-pressure washing or bulldozing (Rolan & Gallagher, 1991; Moore, 2006) but physical abrasion is addressed under the relevant pressure above. Therefore, this pressure was considered to be Not relevant. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Introduction or spread of invasive non-indigenous species (INIS) Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Other INIS [Show more]Other INISEvidenceEssl & Lambdon (2009) reported that that only five species of lichen were thought to be alien in the UK, which is ca 0.3% of the UK's lichen flora. All five species were Parmelia spp. epiphytes and unlikely to occur in the supralittoral. Essl & Lambdon (2009) note that no threat to competing natives has yet been demonstrated. Although they note that information on the presence or spread of non-indigenous lichens is unclear due to the lack of data on lichen distribution across Europe. The Australasian barnacle Austrominius (previously Elminius) modestus was introduced to British waters on ships during the second world war. However, its overall effect on the dynamics of rocky shores has been small as Austrominius modestus has simply replaced some individuals of a group of co-occurring barnacles (Raffaelli & Hawkins, 1999). Although present, monitoring indicates it has not outnumbered native barnacles in the Isle of Cumbrae (Gallagher et al., 2015) it may dominate in estuaries where it is more tolerant of lower salinities than Semibalanus balanoides (Gomes-Filho et al., 2010). The degree of wave exposure experienced by this biotope will limit colonization by Austrominius modestus, which tends to be present in more sheltered biotopes. These results may be applicable to Chthamalus sp. Sensitivity assessment. Overall, there is little evidence of this biotope being adversely affected by non-native barnacle species and limited evidence on the effect of non-native lichens. Therefore, there is currently not enough evidence on which to base an assessment. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Bibliography

Barnes, H. & Barnes, M., 1974. The responses during development of the embryos of some common cirripedes to wide changes in salinity. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 15 (2), 197-202.

Barnes, H. & Barnes, M., 1965. Egg size, nauplius size, and their variation with local, geographical and specific factors in some common cirripedes. Journal of Animal Ecology, 34, 391-402.

Barnes, H. & Stone, R., 1972. Suppression of penis development in Balanus balanoides (L.). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 9 (3), 303-309.

Barnes, H., 1953. The effect of lowered salinity on some barnacle nauplii. Journal of Animal Ecology, 22, 328-330.

Barnes, H., 1957. Processes of restoration and synchronization in marine ecology. The spring diatom increase and the 'spawning' of the common barnacle Balanus balanoides (L.). Année Biologique. Paris, 33, 68-85.

Barnes, H., 1963. Light, temperature and the breeding of Balanus balanoides. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 43 (03), 717-727.

Barnes, M., 1992. The reproductive periods and condition of the penis in several species of common cirripedes. Oceanography and Marine Biology: an Annual Review, 30, 483-525.

Baxter, J.M., 1984. The incidence of Polydora ciliata and Cliona celata boring the shell of Patella vulgata in Orkney. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 64, 728-729.

Bertocci, I., Araujo, R., Vaselli, S. & Sousa-Pinto, I., 2011. Marginal populations under pressure: spatial and temporal heterogeneity of Ascophyllum nodosum and associated assemblages affected by human trampling in Portugal. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 439, 73-82.

Brosnan, D.M. & Crumrine, L.L., 1994. Effects of human trampling on marine rocky shore communities. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 177, 79-97.

Brouardel, J., 1948. Etude du mode d'infestation des Patelles par Urceolaria patellae (Cuenot): influence de l'espece de Patelle. Bulletin du Laboratoire maritime de Dinard, 30, 1-6.

Connell, J.H., 1961b. The influence of interspecific competition and other factors on the distribution of the barnacle Chthamalus stellatus. Ecology, 42 (4), 710-723.

Connell, J.H., 1961. Effects of competition, predation by Thais lapillus, and other factors on natural populations of the barnacle Balanus balanoides. Ecological Monographs, 31, 61-104.

Connor, D.W., Allen, J.H., Golding, N., Howell, K.L., Lieberknecht, L.M., Northen, K.O. & Reker, J.B., 2004. The Marine Habitat Classification for Britain and Ireland. Version 04.05. ISBN 1 861 07561 8. In JNCC (2015), The Marine Habitat Classification for Britain and Ireland Version 15.03. [2019-07-24]. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough. Available from https://mhc.jncc.gov.uk/

Crisp, D. & Patel, B., 1969. Environmental control of the breeding of three boreo-arctic cirripedes. Marine Biology, 2 (3), 283-295.

Crisp, D.J., Southward, A.J. & Southward, E.C., 1981. On the distribution of the intertidal barnacles Chthamalus stellatus, Chthamalus montagui and Euraphia depressa. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 61, 359-380.

Cullinane, J.P., McCarthy, P. & Fletcher, A., 1975. The effect of oil pollution in Bantry Bay. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 6, 173-176.

Davenport, J. & Davenport, J.L., 2005. Effects of shore height, wave exposure and geographical distance on thermal niche width of intertidal fauna. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 292, 41-50.

Davenport, J., Berggren, M.S., Brattegard, T., Brattenborg, N., Burrows, M., Jenkins, S., McGrath, D., MacNamara, R., Sneli, J.-A. & Walker, G., 2005. Doses of darkness control latitudinal differences in breeding date in the barnacle Semibalanus balanoides. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 85 (01), 59-63.

Dethier, M.N., 1994. The ecology of intertidal algal crusts: variation within a functional group. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 177 (1), 37-71.

Dethier, M.N. & Steneck, R.S., 2001. Growth and persistence of diverse intertidal crusts: survival of the slow in a fast-paced world. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 223, 89-100.

Dobson, F.S., 2000. Lichens: an illustrated guide to the British and Irish species. Slough: The Richmond Publishing Co. Ltd.

Ellis, C.J., Coppins, B.J., Dawson, T.P. & Seaward, M.R.D., 2007. Response of British lichens to climate change scenarios: Trends and uncertainties in the projected impact for contrasting biogeographic groups. Biological Conservation, 140 (3–4), 217-235.

Essl, F. & Lambdon, P.W., 2009. Alien Bryophytes and Lichens of Europe. In Handbook of Alien Species in Europe, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 29-41.

Fletcher, A., 1980. Marine and maritime lichens of rocky shores: their ecology, physiology, and biological interactions. In The Shore Environment, vol. 2: Ecosystems (ed. J.H. Price, D.E.G. Irvine & W.F. Farnham), pp. 789-842. London: Academic Press. [Systematics Association Special Volume no. 17(b)].

Foster, B.A., 1971b. On the determinants of the upper limit of intertidal distribution of barnacles. Journal of Animal Ecology, 40, 33-48.

Gallagher, M.C., Davenport, J., Gregory, S., McAllen, R. & O'Riordan, R., 2015. The invasive barnacle species, Austrominius modestus: Its status and competition with indigenous barnacles on the Isle of Cumbrae, Scotland. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 152, 134-141.

Gerson, U & Seaward, M.R.D., 1977. Lichen - invertebrate associations. In Lichen ecology (ed. M.R.D. Seaward), pp. 69-119. London: Academic Press.

Gomes-Filho, J., Hawkins, S., Aquino-Souza, R. & Thompson, R., 2010. Distribution of barnacles and dominance of the introduced species Elminius modestus along two estuaries in South-West England. Marine Biodiversity Records, 3, e58.

Holt, T.J., Hartnoll, R.G. & Hawkins, S.J., 1997. The sensitivity and vulnerability to man-induced change of selected communities: intertidal brown algal shrubs, Zostera beds and Sabellaria spinulosa reefs. English Nature, Peterborough, English Nature Research Report No. 234.

Honeggar, R., 2008. Morphogenesis. In Lichen Biology 2edn. (Nash III, T.H. ed.), pp 69-93. Cambridge, Cambrdige University Press

Jenkins, S., Åberg, P., Cervin, G., Coleman, R., Delany, J., Della Santina, P., Hawkins, S., LaCroix, E., Myers, A. & Lindegarth, M., 2000. Spatial and temporal variation in settlement and recruitment of the intertidal barnacle Semibalanus balanoides (L.)(Crustacea: Cirripedia) over a European scale. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 243 (2), 209-225.

Jenkins, S.R., Beukers-Stewart, B.D. & Brand, A.R., 2001. Impact of scallop dredging on benthic megafauna: a comparison of damage levels in captured and non-captured organisms. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 215, 297-301. DOI https://doi.org/10.3354/meps215297

JNCC (Joint Nature Conservation Committee), 2022. The Marine Habitat Classification for Britain and Ireland Version 22.04. [Date accessed]. Available from: https://mhc.jncc.gov.uk/

JNCC (Joint Nature Conservation Committee), 2022. The Marine Habitat Classification for Britain and Ireland Version 22.04. [Date accessed]. Available from: https://mhc.jncc.gov.uk/

Jones, W.E., Fletcher, A., Hiscock, K. & Hainsworth, S., 1974. First report of the Coastal Surveillance Unit. Feb.-July 1974. Coastal Surveillance Unit, University College of North Wales, Bangor, 1974.

Kronberg, I., 1988. Structure and adaptation of the fauna in the black zone (littoral fringe) along rocky shores in northern Europe. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 49 (1-2), 95-106.

Long, J.D., Cochrane, E. & Dolecal, R., 2011. Previous disturbance enhances the negative effects of trampling on barnacles. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 437, 165-173.

Mieszkowska, N., Burrows, M.T., Pannacciulli, F.G. & Hawkins, S.J., 2014. Multidecadal signals within co-occurring intertidal barnacles Semibalanus balanoides and Chthamalus spp. linked to the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Journal of Marine Systems, 133, 70-76.

Moore, J.J., 2006. State of the marine environment in SW Wales, 10 years after the Sea Empress oil spill. A report to the Countryside Council for Wales from Coastal Assessment, Liaison & Monitoring, Cosheston, Pembrokeshire. CCW Marine Monitoring Report No: 21. 30pp.

Nash III, T.H., 2008. Lichen Biology 2 edn. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Patel, B. & Crisp, D. J., 1960. The influence of temperature on the breeding and the moulting activities of some warm-water species of operculate barnacles. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 36, 667-680.

Povey, A. & Keough, M.J., 1991. Effects of trampling on plant and animal populations on rocky shores. Oikos, 61: 355-368.

Raffaelli, D.G. & Hawkins, S.J., 1996. Intertidal Ecology London: Chapman and Hall.

Ranwell, D.S., 1968. Lichen mortality due to 'Torrey Canyon' oil and decontamination measures. Lichenologist, 4, 55-56.

Rognstad, R.L., Wethey, D.S. & Hilbish, T.J., 2014. Connectivity and population repatriation: limitations of climate and input into the larval pool. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 495, 175-183.

Rolan, R.G. & Gallagher, R., 1991. Recovery of Intertidal Biotic Communities at Sullom Voe Following the Esso Bernicia Oil Spill of 1978. International Oil Spill Conference Proceedings: March 1991, Vol. 1991, No. 1, pp. 461-465. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7901/2169-3358-1991-1-461

Sancho, L.G., Allan Green, T.G. & Pintado, A., 2007. Slowest to fastest: Extreme range in lichen growth rates supports their use as an indicator of climate change in Antarctica. Flora - Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 202 (8), 667-673.

Seaward, M.R.D., 2008. The environmental role of lichens. In Lichen Biology (ed. Nash III, T.H.) pp. 274-298. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Shanks, A.L. & Wright, W.G., 1986. Adding teeth to wave action- the destructive effects of wave-bourne rocks on intertidal organisms. Oecologia, 69 (3), 420-428.

Southward, A.J., 1955. On the behaviour of barnacles. I. The relation of cirral and other activities to temperature. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 34, 403-432.

Southward, A.J., Hawkins, S.J. & Burrows, M.T., 1995. Seventy years observations of changes in distribution and abundance of zooplankton and intertidal organisms in the western English Channel in relation to rising sea temperature. Journal of Thermal Biology, 20, 127-155.

Tighe-Ford, D., 1967. Possible mechanism for the endocrine control of breeding in a cirripede. Nature, 216, 920-921.

Tyler-Walters, H. & Arnold, C., 2008. Sensitivity of Intertidal Benthic Habitats to Impacts Caused by Access to Fishing Grounds. Report to Cyngor Cefn Gwlad Cymru / Countryside Council for Wales from the Marine Life Information Network (MarLIN) [Contract no. FC 73-03-327], Marine Biological Association of the UK, Plymouth, 48 pp. Available from: www.marlin.ac.uk/publications

Wethey, D.S., 1984. Sun and shade mediate competition in the barnacles Chthamalus and Semibalanus: a field experiment. The Biological Bulletin, 167 (1), 176-185.

Wethey, D.S., Woodin, S.A., Hilbish, T.J., Jones, S.J., Lima, F.P. & Brannock, P.M., 2011. Response of intertidal populations to climate: effects of extreme events versus long term change. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 400 (1), 132-144.

Citation

This review can be cited as:

Last Updated: 30/08/2018