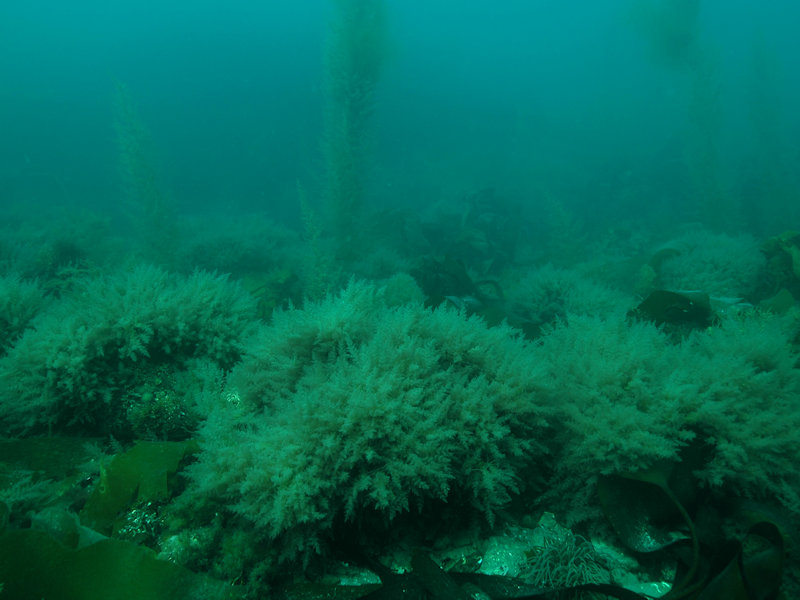

Sargassum muticum on shallow slightly tide-swept infralittoral mixed substrata

| Researched by | Frances Perry, Dr Heidi Tillin, Dr Samantha Garrard & Amy Watson | Refereed by | This information is not refereed |

|---|

Summary

UK and Ireland classification

Description

Mixed substrata from the sublittoral fringe to 5m below chart datum dominated by the brown seaweed Sargassum muticum. This invasive non-native brown seaweed can form a dense canopy on areas of mixed substratum (typically 0-10 % bedrock on 90-100 % sandy sediment). The substrate on which this Sargassum muticum dominated community is able to develop is highly variable, but particularly prevalent on broken rock and pebbles anchored in sandy sediment. The pebbles, cobbles and broken bedrock provide a substrate for alga such as the kelp Saccharina latissima. During the spring, Sargassum muticum has large quantities of epiphytic ectocarpales and may also support some epifauna e.g. the hydroid Obelia geniculata commonly found on kelp. The brown seaweed Chorda filum, which thrives well on these mixed substrata, is also commonly found with Sargassum muticum during the summer months. In Strangford Lough, where this biotope occurs, the amphipod Dexamine spinosa has been recorded to dominate the epiphytic fauna (this is known to be commonly found in Zostera spp. beds). Sargassum muticum is also found on hard, bedrock substrates within Saccharina latissima canopies. Sargassum muticum plants on hard substrate area, under a dense Saccharina latissima canopy, are typically smaller and at a much lower density, especially where a lush, under-storey exists with red seaweeds such as Ceramium nodolosum, Gracilaria gracilis, Chylocladia verticillata, Pterosiphonia plumula and Polysiphonia elongata and the green seaweeds Cladophora sp., Ulva lactuca and Bryopsis plumosa. The anthozoan Anemonia viridis and the crab Necora puber can be present. Information taken from Connor et al. (2004) however more information is necessary to validate this description.

Depth range

0-5 mAdditional information

-

Listed By

Sensitivity review

Sensitivity characteristics of the habitat and relevant characteristic species

The description of this biotope and information on the characterizing species is taken from Connor et al., (2004). This biotope, IR.LIR.K.Sar, describes mixed substrata from the sublittoral fringe to 5m below chart datum (BCD). The invasive non-native species, Sargassum muticum, is the dominant macrophyte within this biotope, and is considered the main characterizing species. Sargassum muticum is able to dominate this shallow sublittoral habitat where the substrata is mixed. When bedrock and boulders contribute to 15 – 100% of the substrata, then Saccharina latissima (syn. Laminaria saccharina) dominates. Within examples of this biotope Saccharina latissima can be found frequently growing on more stable sediment fractions, but is not found in greater abundance than Sargassum muticum. In addition to these phaeophyceae, the Rhodophyta Gracilaria gracilis and Ceramium virgatum (syn. Ceramium nodulosum) are characterizing species of this biotope. This biotope is found in fully marine (30 – 40 psu), wave sheltered conditions, with moderately strong (1 – 3 knots) tidal currents.

Both Sargassum muticum and Saccharina latissima are considered to be ecosystem engineers as they alter the canopy that their fronds create modify habitat conditions. Although other species are important to this biotope, if this species were missing the biotope would still exist. The canopy provides shade for the various underlying seaweeds in addition to providing a substratum for epifauna and being the primary food resource for grazers. This can facilitate the existence and survival of other species and therefore strongly influencing the structure and functioning of the ecosystem. Therefore, the sensitivity assessment is based on the key structuring species, although the sensitivity of other species is addressed where relevant.

Resilience and recovery rates of habitat

Sargassum muticum possesses life history characteristics which make it an effective colonizer and competitor and it is an invasive species across much of its range. The base/holdfast is perennial (Davison, 1999) and is more tolerant of high air temperatures and desiccation (Norton, 1977) allowing the plant to survive and retain space during periods where conditions are less favourable. The high growth rate (10 cm per day), allows this species to rapidly dominate and shade other algae. The species can reproduce sexually and self-fertilize or asexually and reaches reproductive maturity annually from the first year. Detached fronds are able to continue to grow into new plants and to produce germlings which is an effective mechanism for widespread dispersal supporting colonization or recolonization over a wide area. In comparison, like other brown and red algae, dispersal via propagules is limited. According to Lüning (1990), the eggs of most large perennial algae are adapted for rapid sinking. In Sargassum muticum, eggs have a dispersal range of as little as 3 m in the intertidal region (Critchley, 1981; Kendrick & Walker, 1995). Though this distance can increase significantly with water movement (Norton & Fetter, 1981; Deysher & Norton, 1982). Sargassum muticum exploits gaps within native algal cover (Davison, 1999) and then rapidly grows and outshades native algae. Space pre-emption by crustose and turf forming algae inhibits Sargassum muticum recruitment (Britton-Simmons, 2006; Deysher and Norton, 1982) and light pre-emption, by canopy and understorey algae reduces Sargassum muticum survivorship (Britton-Simmons, 2006). Sargassum muticum was first found attached in the British Isles in Bembridge on the Isle of Wight in 1971 (Farnham et al., 1973). Since then it has spread rapidly along the English south coast at about 30 km/year (Farnham et al. 1981). In north-west American the speed of invasion is about 60 km/year, mostly by drifting, fertile adults (Farnham et al. 1981).

Saccharina latissima (formerly Laminaria saccharina) is an opportunistic seaweed which has a relatively fast growth rate. Saccharina lattisma is a perennial kelp which can reach maturity in 15-20 months (Sjøtun, 1993) and has a life expectancy of 2-4 years (Parke, 1948). Saccharina lattisma is widely distributed in the north Atlantic from Svalbard to Portugal (Birket et al., 1998a; Conor et al., 2004; Bekby & Moy 2011; Moy & Christie, 2012). Saccharina lattisima has a heteromorphic life strategy (Edwards, 1998). Mature sporophytes broadcast spawn zoospores from reproductive structures known as sori (South & Burrows, 1967; Birket et al., 1998a). Zoospores settle onto rock and develop into gametophytes, which following fertilization, germinate into juvenile sporophytes. Laminarian zoospores are expected to have a large dispersal range. However, zoospore density and the rate of successful fertilization decreases exponentially with distance from the parental source (Fredriksen et al., 1995). Hence, recruitment can be influenced by the proximity of mature kelp beds producing viable zoospores (Kain, 1979; Fredriksen et al., 1995). Saccharina lattisma recruits appear in late winter early spring beyond which is a period of rapid growth, during which sporophytes can reach a total length of 3 m (Werner & Kraan, 2004). In late summer and autumn growth rates slow and spores are released from autumn to winter (Parke, 1948; Lüning, 1979; Birket et al., 1998a). The overall length of the sporophyte may not change during the growing season due to marginal erosion but growth of the blade has been measured at 1.1 cm/day, with a total length addition of ≥2.25 m per year (Birkett et al., 1998a). Saccharina lattisma is a rapid colonizing species and appear early in algal succession. Leinaas & Christie (1996) removed Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis from “Urchin Barrens” and observed a succession effect. Initially the substrate was colonized by filamentous algae, after a couple of weeks these were out-competed and the habitat dominated by Saccharina latissimi. However, this was subsequently out-competed by Laminaria hyperborea. In the Isle of Man, Kain (1975) cleared sublittoral blocks of Laminaria hyperborea at different times of the year for several years. The first colonizers and succession community differed between blocks and at what time of year the blocks were cleared. Saccharina lattisima was an early colonizer. However, within 2 years of clearance the blocks were dominated by Laminaria hyperborea. In 2002, a 50.7-83% decline of Saccharina latissima was discovered in the Skaggerak region, South Norway (Moy et al., 2006; Moy & Christie, 2012). Survey results indicated a sustained shift from Saccharina latissima communities to those of ephemeral filamentous algal communities. The reason for the community shift was unknown, but low water movement in wave and tidally sheltered areas combined with the impacts of dense human populations, e.g. increased land run-off, was suggested to be responsible for the dominance of ephemeral turf macro-algae. Multiple stressors such as eutrophication, increasing regional temperature, increased siltation and overfishing may also be acting synergistically to cause the observed habitat shift.

Gracilaria gracilis is widely distributed however in the North Atlantic is found from south west Norway (Rueness, 1977) and extends to South Africa (Anderson et al., 1999). Gracilaria gracilis is widely distributed, in the North Atlantic specifically is found from south west Norway (Rueness, 2005) and extends to South Africa (Anderson et al., 1999). Gracilaria gracilis is a perennial red seaweed, individuals are composed of an annual erect thalli which grow from a perennial holdfast (Martín et al., 2011). Gracilaria gracilis has a complex life history; reproducing sexually through haploid and diploid spores (Martín et al., 2011) and through vegetative fragmentation (Rueness et al., 1987). Mature individuals consist of erect annual thalli growing from a perennial holdfast (Martín et al., 2011). Vegetative growth is limited to approximately 6 months each year (Kain & Destcombe, 1995) during which thalli can reach 60cm (Bunker et al., 2012). Thalli become reproductively active within 2 and half months from March-September (Engel & Destombe, 2002). Gracilaria gracilis is recorded throughout the British Isles (AlgaeBase, 2015; NBN, 2015). However, IR.LIR.K.Sar is restricted to the south and south-west of England.

Ceramium spp. may regenerate from very small fragments of thalli attached to the substratum or the development of germlings from settled spores (Dixon, 1960). Ceramium virgatum (syn. Ceramium nodulosum) has been shown to recruit rapidly to cleared surfaces. For instance, experimental panels were colonized by Ceramium virgatum within a month of being placed in both Langstone Harbour (Brown et al., 2001) and in the outer harbour of the Isle of Helgoland (Wollgast et al., 2008).

Resilience sensitivity. Resilience of the species within this biotope have the ability to recover rapidly following disturbance.Sargassum muticum is a highly successful invasive non-native species and has extremely fast growth rates. Saccharina latissima has been shown to be an early colonizer within algal succession, appearing within 2 weeks of clearance, and can reach sexual maturity within 15-20 months. Gracilaria gracilis and Ceramium virgatum have rapid growth rates. Gracilaria gracilis is also capable of reaching sexual maturity within one year. Resilience has therefore been assessed as ‘High’.

The resilience and the ability to recover from human induced pressures is a combination of the environmental conditions of the site, the frequency (repeated disturbances versus a one-off event) and the intensity of the disturbance. Recovery of impacted populations will always be mediated by stochastic events and processes acting over different scales including, but not limited to, local habitat conditions, further impacts and processes such as larval-supply and recruitment between populations. Full recovery is defined as the return to the state of the habitat that existed prior to impact. This does not necessarily mean that every component species has returned to its prior condition, abundance or extent but that the relevant functional components are present and the habitat is structurally and functionally recognisable as the initial habitat of interest. It should be noted that the recovery rates are only indicative of the recovery potential.

Hydrological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Temperature increase (local) [Show more]Temperature increase (local)Benchmark. A 5°C increase in temperature for one month, or 2°C for one year. Further detail EvidenceAverage Sea Surface Temperatures (SST) in the British Isles range from 8-16 °C in summer and 6-13 °C in winter (Beszczynska-Möller & Dye, 2013). This natural variability of temperatures in the British Isles means that there will be different impacts of the pressure at this benchmark depending where in the country the biotope is found. Water temperatures in other parts of Sargassum muticum’s range exceed those which are experienced within the British Isles. Sargassum muticum can grow in water temperatures between 3 °C and 30 °C (Norton, 1977; Hales & Fletcher, 1989). In its native Japan, Sargassum muticum experiences an annual temperature range of between 5 °C and 28 °C. In southern California, it survives in shallow lagoons and tidal pools that reach temperatures of 30 °C and rarely fall below 14 °C (Norton, 1977). In Alaska, Sargassum muticum occurs where temperatures range between 3 °C and 10 °C (Hales & Fletcher, 1989). Strong (2003) found that stands of Sargassum muticum in Strangford Lough caused strong temperature stratification, including significant cooling of the water just above the sediment, while a thin layer at the surface canopy experienced elevated temperatures 11 °C above ambient due to heat absorption of the canopy. Strong (2003) proposed that warmer water temperatures could increase gamete production and extend the reproductive period. The temperature isotherm of 19-20 °C has been reported as limiting Saccharina latissima geographic distribution (Müller et al., 2009). Gametophytes can develop in ≤23 °C (Lüning, 1990) but the optimal temperature range for sporophyte growth is 10-15 °C (Bolton & Lüning, 1982). Bolton & Lüning (1982) experimentally observed that sporophyte growth was inhibited by 50-70 % at 20 °C and following 7 days at 23 °C all specimens completely disintegrated. In the field, Saccharina latissima has shown significant regional variation in its acclimation to temperature changes. Gerard & Dubois (1988) observed sporophytes of Saccharina latissima which were regularly exposed to ≥20 °C could tolerate these temperatures, whereas sporophytes from other populations which rarely experience ≥17 °C showed 100% mortality after 3 weeks of exposure to 20 °C. Therefore the response of Saccharina latissima to a change in temperatures is likely to be locally variable. The optimal temperature for Gracilaria gracilis growth was found to be 18 °C, but high growth was recorded up to 25.5 °C (Rebello et al., 1996). Gracilaria gracilis northern range edge is south western Norway where it exclusively occurs in shallow bays in which summer temperatures exceed 20 °C (Rueness, 1977). Lüning (1990) reported that Ceramium virgatum survived temperatures from 0 to 25 °C with optimal growth occurring at 15 °C. The species is therefore likely to be tolerant of higher temperatures than it experiences in the seas around Britain and Ireland. Sensitivity assessment. A change in this pressure at the benchmark will remove species from their optimal conditions. Sargassum muticum, Gracilaria gracilis and Ceramium virgatum are not likely to be negatively afftected. However, ecotypes of Saccharina lattisima have been shown to have different temperature optimums (Gerard & Dubois, 1988). For acute 5 °C increases in temperature for a period of 1 month combined with high summer temperatures could cause large scale mortality of Saccharina lattisma. A 2 °C increase in temperature for a year, combined with high summer temperatures, could similarly result in large scale mortality of Saccharina lattisima ecotypes. Resistance has been assessed as ‘None’, and resilience as ‘High’, giving the biotope a sensitivity of ‘Medium’. | NoneHelp | HighHelp | MediumHelp |

Temperature decrease (local) [Show more]Temperature decrease (local)Benchmark. A 5°C decrease in temperature for one month, or 2°C for one year. Further detail EvidenceAverage Sea Surface Temperatures (SST) in the British Isles range from 8-16 °C in summer and 6-13 °C in winter (Beszczynska-Möller & Dye, 2013). This natural variability of temperatures in the British Isles means that there will be different impacts of the pressure at this benchmark depending where in the country the biotope is found. The temperature range in which Sargassum muticum may grow is between 3 °C and 30 °C (Norton, 1977; Hales and Fletcher, 1989). Early life stages are more sensitive and reductions in temperature from 17 °C to 7 °C decrease germling growth (Steen, 2003). Sargassum muticum experiences colder waters than the UK over parts of its geographic range and it has successfully invaded the cold waters of southern Alaska (Hales & Fletcher, 1989) and Scandinavia (Karlsson & Loo, 1999). It can survive short periods of freezing temperatures (Norton, 1977), although a single hour exposed to temperatures of -9°C was lethal to the entire plant (Norton, 1977). The branches can survive at –1 ˚C (Norton, 1977) and the holdfast and stipe can survive lower temperatures (Critchley et al., 1987; Karlsson, 1988). In Sweden, early colonists observed in 1987 were noted to survive the winter, despite formation of ice on the nearby sea surface (Karlsson & Loo, 1999). Saccharina lattissima is widespread throughout the arctic. Saccharina lattissima has a lower temperature threshold for sporophyte growth at 0 °C (Lüning, 1990). Subtidal red algae can survive at -2 °C (Lüning, 1990; Kain & Norton, 1990). The distribution and temperature tolerances of these species suggests they likely be unaffected by temperature decreases assessed within this pressure. Gracilaria gracilis is widespread throughout the UK (Bunker et al., 2012). However, the northern range edge of Gracilaria gracilis is within south west Norway, where it is restricted to shallow bays in which summer temperatures exceed 20 °C. Lüning (1990) reported that Ceramium virgatum survived temperatures from 0 to 25 °C with optimal growth at about 15 °C. This species is therefore likely to be tolerant of lower temperatures than it experiences in the seas around Britain and Ireland. Sensitivity assessment. The temperature tolerances of the characterizing species within this biotope suggest that this pressure, at the benchmark, would have limited effect. The range of this biotope is also limited to the south coast of England, where water temperatures are warmer than those further north. Consequently, resistance and resilience are assessed as ‘High’ and the biotope is considered ‘Not Sensitive’. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Salinity increase (local) [Show more]Salinity increase (local)Benchmark. A increase in one MNCR salinity category above the usual range of the biotope or habitat. Further detail EvidenceLocal populations may be acclimated to the prevailing salinity regime and may therefore exhibit different tolerances to other populations subject to different salinity conditions. Therefore caution should be used when inferring tolerances from populations in different regions. This biotope is found in full (30-40 ppt) salinity (Connor et al., 2004). Hales & Fletcher (1989) conducted salinity tolerance experiments on Sargassum muticum germlings collected from Bembridge, Isle of Wight. Germlings were tolerant of salinities 6.8 % – 34 % for the entire four week laboratory experiment (Hales & Fletcher, 1989). Optimal growth occurred at a temperature of 25oC and a salinity of 34 ‰ (Hales & Fletcher, 1989). No evidence was found for tolerance of salinities above 34 ‰. Karsten (2007) tested the photosynthetic ability of Saccharina latissima under acute 2 and 5 day exposure to salinity treatments ranging from 5-60 psu. A control experiment was also carried at 34 psu. Saccharina latissima showed high photosynthetic ability at >80 % of the control levels between 25-55 psu (Karsten, 2007). Optimal salinities for Gracilaria gracilis growth have been recorded at 30 ‰ (Rebello et al., 1996). However, Gracilaria gracilis can be found in rock pools (South & Burrows, 1967; Engel & Destombe, 2002). Therefore, is likely to be able to tolerate higher salinities. Ceramium virgatum can be found in rock pools on the mid shore. The ability of this species to tolerate rock pools where short-term hypersalinity is common, suggests that it has some tolerance to increased salinities. However, the effects of long-term exposure to hypersaline conditions are unknown. Sensitivity assessment. There is little empirical evidence to support this assessment. The information available suggests that the characterizing species within this biotope survive best in fully saline conditions. The ability of these species to tolerate rock pool environments suggests that they can survive in hypersaline conditions for short periods of time. The long-term tolerances for these species to hypersalinities are not known. This uncertainty has resulted in a resistance of ‘Medium’, a resilience of ‘High’. Giving a sensitivity of ‘Low’. | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Salinity decrease (local) [Show more]Salinity decrease (local)Benchmark. A decrease in one MNCR salinity category above the usual range of the biotope or habitat. Further detail EvidenceHales & Fletcher (1989) conducted salinity tolerance experiments on Sargassum muticum germlings collected from Bembridge, Isle of Wight. In experimentation germlings were tolerant of salinities 6.8 – 34 % for the entire four week laboratory experiment (Hales & Fletcher, 1989). Optimal growth occurred at a temperature of 25 oC and a salinity of 34 % (Hales & Fletcher, 1989). No evidence was found for tolerance of salinities above 34 %. Norton (1977) found that, in culture, vegetative branches of Sargassum muticum could tolerate minimum salinities down to 9 ppt but growth rates were much reduced. Transplanted mature plants (Steen, 2004) were also found to show a decrease in growth and reproductive rate at a station with salinities in the range of approximately 9.5 ppt to 17.4 ppt over a six month period. Field studies have also observed an absence of Sargassum muticum in shallow Alaskan waters (6 m) at a salinity of 8.64 ppt due to snow melt (Norton, 1977). Steen (2004) suggested that Sargassum muticums invasive capability decreased at lower salinities. In salinities below 15 ppt Sargassum muticum can no longer successfully invade a habitat. Sargassum muticum becomes less competitive with other species at salinities lower than 25 ppt. However, since brackish ecosystems are often characterized by low biodiversity, it has been hypothesised that these areas will be more vulnerable to colonization by Sargassum muticum if it is able to withstand hyposaline conditions (Elmgren & Hill, 1997). Karsten (2007) tested the photosynthetic ability of Saccharina latissima under acute two and five day exposure to salinity treatments ranging from 5-60 psu. A control experiment was also carried at 34 psu. Saccharina latissima showed high photosynthetic ability at >80 % of the control levels between 25-55 psu. Hyposaline treatment of 10-20 psu led to a gradual decline of photosynthetic ability. After 2 days at 5 psu Saccharina latissima showed a significant decline in photosynthetic ability at approximately 30 % of control. After 5 days at 5 psu Saccharina latissima specimens became bleached and showed signs of severe damage. The experiment was conducted on Saccharina latissima from the Arctic, and the authors suggest that at extremely low water temperatures (1-5°C) macroalgae acclimation to rapid salinity changes could be slower than at temperate latitudes. It is therefore possible that resident Saccharina latissima of the UK maybe be able to acclimate to salinity changes more effectively. Gracilaria gracilis can reportedly tolerate wide salinity fluctuations (Bunker et al., 2012). Furthermore Gracilaria gracilis is recorded from biotopes which occur in reduced salinity regimes (<18-40‰), such as SS.SMp.KSwSS.SlatGraVS (Connor et al., 2004) which suggests Gracilaria gracilis can tolerate low salinity environments. Ceramium virgatum occurs over a very wide range of salinities. The species penetrates almost to the innermost part of Hardanger Fjord in Norway where it experiences very low salinity values and large salinity fluctuations due to the influence of snowmelt in spring (Jorde & Klavestad, 1963). Sensitivity assessment. A change from a fully marine (30 – 40 psu) regime to a variable salinity (18 – 40 psu) for a year will lead to a loss of biodiversity within this biotope. Sargassum muticum, Gracilaria gracilis and Ceramium virgatum are all able to tolerate fluctuations in salinities. However, Saccharina latissima kept in lower salinities (e.g. 10 – 20 psu) begin to lose their ability to photosynthesise (Karsten, 2007). A change in the pressure in this benchmark is likely to see a reduction in Saccharina latissima, and all of the epifauna associated with this ecosystem engineering characteristic species. However, the three remaining species are likely to be able to persevere. Resistance has been assessed as ‘Medium’ and resilience as ‘High’. Therefore the sensitivity of this biotope to a decrease in salinity has been assessed as ‘Low’. | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Water flow (tidal current) changes (local) [Show more]Water flow (tidal current) changes (local)Benchmark. A change in peak mean spring bed flow velocity of between 0.1 m/s to 0.2 m/s for more than one year. Further detail EvidenceWater motion is a key determinant of marine macroalgal production, directly or indirectly influencing physiological rates and community structure (Hurd, 2000). Higher water flow rates increase mechanical stress on macroalgae by increasing drag. This can result in individuals being torn off the substratum. Once removed, the attachment cannot be reformed causing the death of the algae. Any sessile organism attached to the algae will also be lost. Many macroalgae are, however, highly flexible and are able to re-orientate their position in the water column to become more streamlined. This ability allows algae to reduce the relative velocity between algae and the surrounding water, thereby reducing drag and lift (Denny et al., 1998). Propagule dispersal, fertilization, settlement, and recruitment are also influenced by water movement (Pearson & Brawley, 1996). In addition, increased water flow will cause scour though greater sediment movement affecting in particular small life stages of macroalgae by removing new recruits from the substratum and hence reducing successful recruitment (Devinny & Volse, 1978) (see ‘siltation’ pressures). On the other hand, a reduction in water flow can cause a thicker boundary layer resulting in lower absorption of nutrients and CO2 by the macroalgae. Slower water movement can also cause oxygen deficiency directly impacting the fitness of algae (Olsenz, 2011). No empirical information could be found on the tolerance of either Sargassum muticum, Gracilaria gracilis or Ceramium virgatum to an increase in water flow. Peteiro & Freire (2013) measured Saccharina latissima growth from two sites, the first had maximal water velocities of 0.3 m/sec and the second had 0.1 m/sec. At the first site Saccharina latissima had significantly larger biomass than at site two (16 kg/m to 12 kg/m respectively). Peteiro & Freire (2013) suggested that faster water velocities were beneficial to Saccharina latissima growth. However, Gerard & Mann (1979) measured Saccharina latissima productivity at greater water velocities and found Saccharina latissima productivity was reduced in moderately strong tidal streams (≤1 m/sec) when compared to weak tidal streams (<0.5 m/sec). Sensitivity assessment. An increase in water movement can cause a reduction in algae cover due to an increase in the physical stress exerted on them. Reduction in reproduction and recruitment success may also occur. However, at the level of the benchmark an increase in water flow is unlikely to have a negative impact on the characterizing species within this biotope. Resistance has been recorded as ‘High’ and resilience is recorded as ‘High’ giving an overall sensitivity of ‘Not Sensitive’. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Emergence regime changes [Show more]Emergence regime changesBenchmark. 1) A change in the time covered or not covered by the sea for a period of ≥1 year or 2) an increase in relative sea level or decrease in high water level for ≥1 year. Further detail EvidenceIR.LIR.K.Sar is found from the sublittoral fringe into the shallow sublittoral. Therefore, this biotope is likely to be exposed during some extreme spring low tides. During which time the biotope would be emersed for short periods of time. Consequently the characterizing species must have some tolerance to very short periods of exposure to air. However, as this biotope is sublittoral in nature any increase in emergence will cause mortality of the characterizing species, and the loss of the biotope. Sargassum muticum is found on the lower shore and sublittoral and in rockpools. Although rockpools allow Sargassum muticum to occur further up the shore, individuals in rock pools are usually smaller and may have lower reproductive rates (plants are often small and reproduction may be impaired (Fletcher & Fletcher, 1975a). Fronds exposed to air in hot sunshine can die within an hour and three hours exposure can kill fronds in the shade (Norton, 1977). An increase in emergence may therefore expose Sargassum muticum to unfavourable conditions resulting in reduced growth or mortality. The holdfast can survive and is more resistant to desiccation, so that recovery may be rapid from short-term desiccation events. The algal mat covering the substratum, predominantly of the red seaweed Ceramium virgatum, may be more intolerant of an increase in desiccation. Ceramium virgatum occurs profusely in rockpools, on the lower shore and in the subtidal but not on the open shore away from damp places suggesting that it is intolerant of desiccation. As a consequence of an increase in emergence, the algal cover may become diminished. Sensitivity assessment. Resistance has been assessed as ‘Low’ and resilience as ‘High’. Therefore, sensitivity of this biotope to a change in emergence is considered as ‘Low’. | LowHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Wave exposure changes (local) [Show more]Wave exposure changes (local)Benchmark. A change in near shore significant wave height of >3% but <5% for more than one year. Further detail EvidenceAn increase in wave exposure generally leads to a decrease in macroalgae abundance and size (Lewis, 1961, Stephenson & Stephenson, 1972, Hawkins et al., 1992, Jonsson et al., 2006). Many macroalgae are highly flexible but not physically robust and an increase in wave exposure can cause mechanical damage, breaking fronds or even dislodging whole algae from the substratum. All of the characterizing species within this biotope are permanently attached to the substratum and would not be able to re-attach if removed. Organisms living on the fronds and holdfasts will be washed away with the algae, whereas more mobile species could find new habitat in surrounding areas. The structure of kelps enables them to survive a range of wave conditions from exposed to sheltered conditions (Connor et al., 2004, Harder et al., 2006). Physiological differences between kelps are evident between low wave exposure and medium-high wave exposure. No empirical information can be found on the effects of wave exposure on Sargassum muticum or Ceramium virgatum. Bunker et al. (2012) reports that Gracilaria gracilis is most common in wave sheltered sites. However, Gracilaria gracilis has been recorded from biotops that are recorded from moderately wave exposed conditions (e.g. SS.SMp.KSwSS.SlatGraFS) (Connor et al., 2004). Sensitivity assessment. This biotope is found from extremely sheltered to sheltered conditions. An increase in local wave height (e.g. to strong or moderately strong exposure) may increase local sediment mobility, potentially increase dislodgment or relocation of the characterizing species (South & Burrows, 1967; Birkett et al., 1998b). An increase in wave exposure, may therefore result in significant change to or loss of the biotope. However, an increase in nearshore significant wave height of 3-5% is not likely to have a significant effect on biotope structure. Resistance has been assessed as ‘High’, and resilience as ‘High’. Therefore sensitivity has been assessed as ‘Not Sensitive’ at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Chemical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Transition elements & organo-metal contamination [Show more]Transition elements & organo-metal contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed but evidence is presented where available. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Hydrocarbon & PAH contamination [Show more]Hydrocarbon & PAH contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed but evidence is presented where available. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Synthetic compound contamination [Show more]Synthetic compound contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed but evidence is presented where available. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Radionuclide contamination [Show more]Radionuclide contaminationBenchmark. An increase in 10µGy/h above background levels. Further detail EvidenceNo evidence. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Introduction of other substances [Show more]Introduction of other substancesBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

De-oxygenation [Show more]De-oxygenationBenchmark. Exposure to dissolved oxygen concentration of less than or equal to 2 mg/l for one week (a change from WFD poor status to bad status). Further detail EvidenceNo direct evidence was found to assess this pressure for any of the characterizing species. For this reason an assessment of ‘No Evidence’ has been given. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Nutrient enrichment [Show more]Nutrient enrichmentBenchmark. Compliance with WFD criteria for good status. Further detail EvidenceConolly & Drew (1985) found Saccharina latissima sporophytes had relatively higher growth rates when in close proximity to a sewage outlet in St Andrews, UK, compared to other sites along the east coast of Scotland. At St Andrews, nitrate levels were 20.22µM, which represents an approximate 25 % increase compared to other sites (approx. 15.87 µM). Handå et al. (2013) also reported that Saccharina latissima sporophytes grew approx. 1 % faster per day when in close proximity to Norwegian salmon farms, where elevated ammonium could be readily absorbed by sporophytes. Read et al. (1983) reported after the installation of a new sewage treatment works, which reduced the suspended solid content of liquid effluent by 60 % in the Firth of Forth, Saccharina latissima became abundant where previously it had been absent. Bokn et al. (2003) conducted a nutrient loading experiment on intertidal fucoids. Three years into the experiment no significant effect had been observed in the communities. However, four years into the experiment a shift occurred from perennials to ephemeral algae. Although Bokn et al. (2003) focussed on fucoids the results could indicate that long-term (>4 years) nutrient loading can result in community shift to ephemeral algae species. Disparities between the findings of the aforementioned studies are likely to be related to the level of organic enrichment. Smit (2002) suggested that dissolved inorganic nitrogen from fish factory waste in Saldanha Bay, South Africa could maintain Gracilaria gracilis growth when natural nutrient sources were low. Hily et al. (1992) found that, in conditions of high nutrients, Ceramium virgatum (as Ceramium rubrum) dominated substrata in the Bay of Brest, France. Ceramium spp. are also mentioned by Holt et al. (1995) as likely to smother other species of macroalgae in nutrient enriched waters. Fletcher (1996) quoted Ceramium virgatum (as Ceramium rubrum) to be associated with nutrient enriched waters. Therefore, algal stands of Ceramium virgatum are likely to benefit from elevated levels of nutrients. Johnston & Roberts (2009) conducted a meta-analysis, which reviewed 216 papers to assess how a variety of contaminants (including sewage and nutrient loading) affected 6 marine habitats (including subtidal reefs). A 30-50 % reduction in species diversity and richness was identified from all habitats exposed to the contaminant types. Johnston & Roberts (2009) also highlighted that macroalgal communities are relative tolerant to contamination, but that contaminated communities can have low diversity assemblages which are dominated by opportunistic and fast growing species (Johnston & Roberts, 2009 and references therein). No evidence was available on the impact of nutrient enrichment on the characterizing species Sargassum muticum. Sensitivity assessment. Although short-term exposure to nutrient enrichment may not affect seaweeds directly, indirect effects such as turbidity may significantly affect photosynthesis and result in reduced growth and reproduction and increased competition form fast growing but ephemeral species. However, the pressure benchmark is set at compliance with Water Framework Directive (WFD) criteria for good status, based on nitrogen concentration (UKTAG, 2014). Therefore, this biotope is considered to be 'Not sensitive' at the pressure benchmark. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Organic enrichment [Show more]Organic enrichmentBenchmark. A deposit of 100 gC/m2/yr. Further detail EvidenceThe organic enrichment of a marine environment at this pressure benchmark leads to organisms no longer being limited by the availability of organic carbon. The consequent changes in ecosystem functions can lead to the progression of eutrophic symptoms (Bricker et al., 2008), changes in species diversity and evenness (Johnston & Roberts, 2009) and decreases in dissolved oxygen and uncharacteristic microalgae blooms (Bricker et al., 1999, 2008). Conolly & Drew (1985) found Saccharina latissima sporophytes had relatively higher growth rates when in close proximity to a sewage outlet in St Andrews, UK, compared to other sites along the east coast of Scotland. At St Andrews, nitrate levels were 20.22µM, which represents an approx. 25% increase compared to other sites (approx. 15.87 µM). Handå et al. (2013) also reported Saccharina latissima sporophytes grew approximately 1 % faster per day when in close proximity to Norwegian salmon farms, where elevated ammonium could be readily absorbed by sporophytes. Read et al. (1983) reported after the installation of a new sewage treatment works, which reduced the suspended solid content of liquid effluent by 60% in the Firth of Forth, Saccharina latissimi became abundant where previously it had been absent. Bokn et al. (2003) conducted a nutrient loading experiment on intertidal fucoids. Three years into the experiment no significant effect had been observed in the communities. However, four years into the experiment a shift occurred from perennials to ephemeral algae. Although Bokn et al. (2003) focussed on fucoids the results could indicate that long-term (>4 years) nutrient loading can result in community shift to ephemeral algae species. Disparities between the findings of the aforementioned studies are likely to be related to the level of organic enrichment. No direct evidence can be found for Sargassum muticum, Gracilaria gracilis or Ceramium virgatum. Johnston & Roberts (2009) undertook a review and meta-analysis of the effect of contaminants on species richness and evenness in the marine environment. Of the 49 papers reviewed relating to sewage as a contaminant, over 70% found that it had a negative impact on species diversity, <5% found increased diversity, and the remaining papers finding no detectable effect. Not all of the 49 papers considered the impact of sewage on the shallow sublittoral. Yet this finding is still relevant as the meta-analysis revealed that the effect of marine pollutants on species diversity were ‘remarkably consistent’ between habitats (Johnston & Roberts, 2009). It was found that any single pollutant reduced species richness by 30-50% within any of the marine habitats considered (Johnston & Roberts, 2009). Throughout their investigation there were only a few examples where species richness was increased due to the anthropogenic introduction of a contaminant. These examples were almost entirely from the introduction of nutrients, either from aquaculture or sewage outfalls. Organic enrichment alters the selective environment by favouring fast growing, ephemeral species such as Ulva lactuca and Ulva intestinalis (Berger et al., 2004, Kraufvelin, 2007). Rohde et al. (2008) found that both free growing filamentous algae and epiphytic microalgae can increase in abundance with nutrient enrichment. This stimulation of annual ephemerals may accentuate the competition for light and space and hinder perennial species development or harm their recruitment (Berger et al., 2003; Kraufvelin et al., 2007). Nutrient enriched environments can not only increase algae abundance, but the abundance of grazing species (Kraufvelin, 2007). Sensitivity assessment. Little empirical evidence was found to support an assessment of this biotope at this benchmark. IR.LIR.K.Sar occurs in sheltered to extremely sheltered wave exposures. It does occur in moderately strong tidal streams (1 – 3 knots) (Connor et al., 2004). This water flow will disperse organic matter reducing the level of exposure quickly after the pressure event. Due to the potential negative impacts that have been reported to result from the introduction of excess organic carbon, resistance has been assessed as ‘Medium’ and resilience has been assessed as ‘High’. This gives an overall sensitivity score of ‘Low’. | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Physical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Physical loss (to land or freshwater habitat) [Show more]Physical loss (to land or freshwater habitat)Benchmark. A permanent loss of existing saline habitat within the site. Further detail EvidenceAll marine habitats and benthic species are considered to have a resistance of ‘None’ to this pressure and to be unable to recover from a permanent loss of habitat (resilience is ‘Very Low’). Sensitivity within the direct spatial footprint of this pressure is therefore ‘High’. Although no specific evidence is described confidence in this assessment is ‘High’, due to the incontrovertible nature of this pressure. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical change (to another seabed type) [Show more]Physical change (to another seabed type)Benchmark. Permanent change from sedimentary or soft rock substrata to hard rock or artificial substrata or vice-versa. Further detail EvidenceIf sediment were replaced with rock or artificial substrata, this would represent a fundamental change to the biotope. All the characterizing species within this biotope can grow in rock biotopes (Birkett et al., 1998b; Connor et al., 2004). However, IR.LIR.K.Sar, by definition is a mixed substrata biotope and a change in sediment to rock would change the biotope into a rock based habitat complex. Sensitivity assessment. Resistance to the pressure is considered ‘None’, and resilience ‘Very low’. Sensitivity has been assessed as ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical change (to another sediment type) [Show more]Physical change (to another sediment type)Benchmark. Permanent change in one Folk class (based on UK SeaMap simplified classification). Further detail EvidenceThe benchmark for this pressure refers to a change in one Folk class. The pressure benchmark originally developed by Tillin et al. (2010) used the modified Folk triangle developed by Long (2006) which simplified sediment types into four categories: mud and sandy mud, sand and muddy sand, mixed sediments and coarse sediments. The change referred to is therefore a change in sediment classification rather than a change in the finer-scale original Folk categories (Folk, 1954). The change in one Folk class is considered to relate to a change in classification to adjacent categories in the modified Folk triangle. For mixed sediments and sand and muddy sand habitats a change in one Folk class may refer to a change to any of the sediment categories. IR.LIR.K.Sar occurs on mixed substrata, therefore within this pressure a change in one folk class relates to a change to either “Coarse sediment”, “Mud and sandy Mud” and “Sand and sandy mud”. Macroalgae are likely to successfully recruit onto the larger sediment/small rock fractions within these biotopes (e.g. gravel, pebbles, cobbles). Therefore, if the proportion of stabilised large sediment/small rock fractions increased this may benefit these biotopes. Conversely if the proportion of smaller sediment fractions increased within these biotopes (as with “Mud and sandy Mud” and “Sand and sandy mud”) then macro-algal recruitment would likely be significantly reduced. Sensitivity assessment. Resistance has been assessed as ‘None’ and resilience as Very low (the pressure is a permanent change) Therefore sensitivity has been assessed as ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Habitat structure changes - removal of substratum (extraction) [Show more]Habitat structure changes - removal of substratum (extraction)Benchmark. The extraction of substratum to 30 cm (where substratum includes sediments and soft rock but excludes hard bedrock). Further detail EvidenceThe species characterizing this biotope occur on rock and would be sensitive to the removal of the habitat. However, extraction of rock substratum is considered unlikely and this pressure is considered to be ‘Not relevant’ to hard substratum habitats. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Abrasion / disturbance of the surface of the substratum or seabed [Show more]Abrasion / disturbance of the surface of the substratum or seabedBenchmark. Damage to surface features (e.g. species and physical structures within the habitat). Further detail EvidenceAbrasion of the substratum e.g. from bottom or pot fishing gear, cable laying etc. may cause localised mobility of the substrata and mortality of the resident community. The effect would be situation dependent. However, if bottom fishing gear were towed over a site it may mobilise a high proportion of the substrata and cause high mortality in the resident community. The effect of trampling on shallow algal communities was examined by a single Mediterranean study (Milazzo et al., 2002). Experimental trampling of 18 transects were carried out at 0, 10, 25, 50, 100 and 150 passes and the community examined immediately after and three months later in the shallow infralittoral (0.3-0.5 m below mean low water). Percentage cover and canopy were significantly affected by trampling, the degree of effect increasing in proportion with trampling intensity. Intermediate trampling treatments (25, 50 and 100 tramples) were similar in effect but significantly different from 0 and 10 tramples. After 150 tramples, percentage cover was significantly lower. Erect macroalgae were particularly susceptible, e.g. the canopy forming Cystoseira brachicarpa v. balearica and Dictyota mediterranea. At low to intermediate trampling intensity, Dictyota mediterranea was strongly damaged while Cystoseira brachicarpa v. balearica lost fronds. At high trampling intensities, Dictyota mediterranea was completely removed while Cystoseira brachicarpa v. balearica was reduced to holdfasts. Low to intermediate trampling intensities (10, 25, 50 tramples) resulted in a loss of algal biomass of 50 g/m2 , while 100 or 150 tramples resulted in a loss of ca 150 g/m2. Recovery was incomplete after three months and significant differences in effect were still apparent between trampling treatments. Overall, trampling reduced percentage algal cover and canopy. However, the study focused on the canopy forming species and lower turf forming species were not mentioned. In summary the above evidence suggests that shallow infralittoral algal communities are susceptible to the effects of trampling by pedestrians. Again the canopy forming, erect species seem to be the most susceptible. Trampling of sublittoral fringe communities could occur as coasteerers haul themselves out of the water at the bottom of the shore. Therefore, sublittoral fringe communities in the UK could be susceptible but there is limited evidence at present (Tyler-Walters 2005). Sensitivity assessment. Resistance has been assessed as ‘Low’, Resilience as ‘High’. Sensitivity has been assessed as ‘Low’. | LowHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Penetration or disturbance of the substratum subsurface [Show more]Penetration or disturbance of the substratum subsurfaceBenchmark. Damage to sub-surface features (e.g. species and physical structures within the habitat). Further detail EvidenceThe characterizing species of this biotope occurs on rock which is resistant to subsurface penetration. The assessment for abrasion at the surface only is therefore considered to equally represent sensitivity to this pressure. | LowHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Changes in suspended solids (water clarity) [Show more]Changes in suspended solids (water clarity)Benchmark. A change in one rank on the WFD (Water Framework Directive) scale e.g. from clear to intermediate for one year. Further detail EvidenceSuspended Particle Matter (SPM) concentration has a positive linear relationship with sub surface light attenuation (Kd) (Devlin et al., 2008). Light availability and water turbidity are principal factors in determining depth range at which macroalgae can be found (Birkett et al., 1998bb). No direct evidence was found to assess Sargassum muticum. As this species is buoyant and floats on the surface of rockpools it is considered to be relatively resistant to an increase in suspended sediments at the pressure benchmark, although some sublethal reductions in photosynthesis may occur due to decreased light penetration on lower branches and increased scour on tissues. Light penetration influences the maximum depth at which laminarians can grow and it has been reported that laminarians grow at depths at which the light levels are reduced to 1 percent of incident light at the surface. Maximal depth distribution of laminarians therefore varies from 100 m in the Mediterranean to only 6-7 m in the silt laden German Bight. In Atlantic European waters, the depth limit is typically 35 m. In very turbid waters the depth at which kelp is found may be reduced, or in some cases excluded completely (e.g. Severn Estuary), because of the alteration in light attenuation by suspended sediment (Lüning, 1990; Birkett et al. 1998a). Laminarians show a decrease of 50% photosynthetic activity when turbidity increases by 0.1/m (light attenuation coefficient =0.1-0.2/m; Staehr & Wernberg, 2009). However, IR.LIR.K.Sar does not extend below 5 m and consequently is unlikely to be negatively affected at the pressure benchmark. Red algae are known to be shade tolerant and are common components of the understorey on seaweed dominated shores. Therefore, a decrease in light intensity is unlikely to adversely affect the biotope. An increase in light intensity is unlikely to adversely affect the biotope as plants can acclimate to different light levels. Hily et al. (1992) found that, in conditions of high turbidity, the characterizing species Ceramium virgatum (as Ceramium rubrum) dominated sediments in the Bay of Brest, France. It is most likely that Ceramium virgatum thrived because other species of algae could not. Whilst the field observations in the Bay of Brest suggested that an increase in abundance of Ceramium virgatum might be expected in conditions of increased turbidity, populations where light becomes limiting will be adversely affected. However, in shallow depths and the intertidal, photosynthesis can occur during low tides (as long as sediments are not deposited) and Ceramium virgatum may benefit from increased turbidity through decreased competition. Sensitivity Assessment. A decrease in turbidity is likely to support enhanced growth (and possible habitat expansion) and is therefore not considered in this assessment. An increase in water turbidity is likely to primarily affect photosynthesis therefore growth and density of the canopy forming seaweeds. Resistance is therefore assessed as ‘High’ and resilience as ‘High’ so that the biotope is considered to be ‘Not sensitive’. An increase in suspended solids above the pressure benchmark may result in a change in species composition with an increase in species seen in very turbid, silty environments. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Smothering and siltation rate changes (light) [Show more]Smothering and siltation rate changes (light)Benchmark. ‘Light’ deposition of up to 5 cm of fine material added to the seabed in a single discrete event. Further detail EvidenceSmothering by 5 cm of sediment material during a discrete event, is unlikely to damage mature examples of Saccharina latissima or Sargassum muticum. However, it may provide a physical barrier to zoospore settlement and therefore could negatively impact on recruitment processes (Moy & Christie, 2012). Laboratory studies showed that kelp and gametophytes can survive in darkness for between 6-16 months at 8 °C. Saccharina latissima would probably survive smothering by a discrete event and once returned to normal conditions gametophytes resumed growth or maturation within one month (Dieck, 1993). There is no information on the effect of smothering on the other characterizing species, Gracilaria gracilis and Ceramium virgatum. Gracilaria gracilis and Ceramium virgatum reach a maximum of 60 cm and 51 cm respectively. Mature organisms are unlikely to be negatively affected by 5 cm of sediment deposits. However, juveniles are more likely to die due to sediment deposition. IR.LIR.K.Sar is recorded in moderately strong tidal streams (≤1.5 m/sec) (Connor et al., 2004). In tidally exposed biotopes deposited sediment is unlikely to remain for more than a few tidal cycles (due to water flow or wave action). In sheltered biotopes deposited sediment could remain but are unlikely to remain for longer than a year. Sensitivity assessment. Deposition of 5 cm of fine material in a single incident is unlikely to result in significant mortality before sediments are removed by current and wave action. Burial will lower survival and germination rates of algal spores and may lead to some mortality of spores and early stages of foliose red algae. Adults are likely to be more resistant to this pressure at the benchmark. However, there is very little evidence to support the assessment. Although there may be some mortality of some species in the biotope the characterizing species are unlikely to experience mortality due to this pressure at the benchmark. Resistance is assessed as ‘High’ based on the likely rapid removal of the majority of smothering sediments within a couple of tidal cycles, resistance will be lower where sediment remains in place for longer. Resilience is assessed also assessed as ‘High’. Overall the biotope is considered to be ‘Not Sensitive’ at the level of the benchmark. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Smothering and siltation rate changes (heavy) [Show more]Smothering and siltation rate changes (heavy)Benchmark. ‘Heavy’ deposition of up to 30 cm of fine material added to the seabed in a single discrete event. Further detail EvidenceNo evidence was found to assess this pressure at the benchmark. A deposit at the pressure benchmark would cover all species with a thick layer of fine materials. Species associated with this biotope such as limpets and littorinids would not be able to escape and would likely suffer mortality (see evidence for light siltation). Sensitivity to this pressure will be mediated by site-specific hydrodynamic conditions and the footprint of the impact. Where a large area is covered sediments may be shifted by water currents rather than removed. Mortality will depend on the duration of smothering; where wave action rapidly mobilises and removes fine sediments, survival of the characterizing and associated species may be much greater. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Litter [Show more]LitterBenchmark. The introduction of man-made objects able to cause physical harm (surface, water column, seafloor or strandline). Further detail EvidenceNot assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Electromagnetic changes [Show more]Electromagnetic changesBenchmark. A local electric field of 1 V/m or a local magnetic field of 10 µT. Further detail EvidenceNo evidence. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Underwater noise changes [Show more]Underwater noise changesBenchmark. MSFD indicator levels (SEL or peak SPL) exceeded for 20% of days in a calendar year. Further detail EvidenceSpecies characterizing this habitat do not have hearing perception but vibrations may cause an impact, however no studies exist to support an assessment. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Introduction of light or shading [Show more]Introduction of light or shadingBenchmark. A change in incident light via anthropogenic means. Further detail EvidenceShading of this biotope (e.g. by the construction of pontoons or jetties) would limit the availability of light, and have similar effects to that of increased turbidity (see above) in the affected area. Sargassum muticum and kelp species are likely to be excluded, while shade tolerant red algae may increase in abundance, or be reduced to encrusting corallines or faunal turfs depending on the degree of shading. Sensitivity assessment. There is so little evidence upon which to base this assessment. The sensitivity assessment has been given as ‘No evidence’. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Barrier to species movement [Show more]Barrier to species movementBenchmark. A permanent or temporary barrier to species movement over ≥50% of water body width or a 10% change in tidal excursion. Further detail EvidenceNot relevant – This pressure is considered applicable to mobile species, e.g. fish and marine mammals rather than seabed habitats. Physical and hydrographic barriers may limit propagule dispersal. But propagule dispersal is not considered under the pressure definition and benchmark. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Death or injury by collision [Show more]Death or injury by collisionBenchmark. Injury or mortality from collisions of biota with both static or moving structures due to 0.1% of tidal volume on an average tide, passing through an artificial structure. Further detail EvidenceNot relevant to seabed habitats. NB. Collision by grounding vessels is addressed under ‘surface abrasion’. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Visual disturbance [Show more]Visual disturbanceBenchmark. The daily duration of transient visual cues exceeds 10% of the period of site occupancy by the feature. Further detail EvidenceNot relevant. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Biological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Genetic modification & translocation of indigenous species [Show more]Genetic modification & translocation of indigenous speciesBenchmark. Translocation of indigenous species or the introduction of genetically modified or genetically different populations of indigenous species that may result in changes in the genetic structure of local populations, hybridization, or change in community structure. Further detail EvidenceKey characterizing species within this biotope are not cultivated or translocated. This pressure is therefore considered not relevant to this biotope. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Introduction or spread of invasive non-indigenous species [Show more]Introduction or spread of invasive non-indigenous speciesBenchmark. The introduction of one or more invasive non-indigenous species (INIS). Further detail EvidenceUndaria pinnatifida has received a large amount of research attention as a major INIS which could out-compete native UK kelp habitats (Farrell & Fletcher, 2006; Thompson & Schiel, 2012; Brodie et al., 2014; Heiser et al., 2014). Undaria pinnatifida was first recorded in the UK, Hamble Estuary, in June 1994 (Fletcher & Manfredi, 1995) and has since spread to a number of British ports. Undaria pinnatifida is an annual species, sporophytes appear in Autumn and grow rapidly throughout winter and spring during which they can reach a length of 1.65 m (Birkett et al., 1998bb). Farrell & Fletcher (2006) suggested that native short-lived species that occupy similar ecological niches to Undaria pinnatifida, such as Saccharina latissima or Chorda filum, are likely to be worst affected and out-competed by Undaria pinnatifida. Where present, an abundance of Undaria pinnatifida has corresponded to a decline in Saccharina lattisima (Farrel & Fletcher, 2006) and Laminaria hyperborea (Hieser et al., 2014). In New Zealand, Thompson & Schiel (2012) observed that native fucoids could out-compete Undaria pinnatifida and re-dominate the substratum. However, Thompson & Schiel (2012) suggested the fucoid recovery was partially due to an annual Undaria pinnatifida die back, which as noted by Heiser et al., (2014) does not occur in Plymouth sound, UK. Undaria pinnatifida was successfully eradicated on a sunken ship in Clatham Islands, New Zealand, by applying a heat treatment of 70 °C (Wotton et al., 2004). However, numerous other eradication attempts have failed, and as noted by Fletcher & Farrell, (1999) once established Undaria pinnatifida resists most attempts of long-term removal. The biotope is unlikely to fully recover until Undaria pinnatifida is fully removed from the habitat, which as stated above is unlikely to occur. The carpet sea squirt Didemnum vexillum (syn. Didemnum vestitum; Didemnum vestum) is a colonial ascidian with rapidly expanding populations that have invaded most temperate coastal regions around the world (Kleeman, 2009; Stefaniak et al., 2012; Tillin et al., 2020). It is an ‘ecosystem engineer’ that can change or modify invaded habitats and alter biodiversity (Griffith et al., 2009; Mercer et al., 2009). Didemnum vexillum has colonized and established populations in the northeast Pacific, Canadian and USA coast; New Zealand; France, Spain, and the Wadden Sea, Netherlands; the Mediterranean Sea and Adriatic Sea (Bullard et al., 2007; Coutts & Forrest, 2007; Dijkstra et al., 2007; Valentine et al., 2007a; Valentine et al., 2007b; Lambert, 2009; Hitchin, 2012; Tagliapietra et al., 2012; Gittenberger et al., 2015; Vercaemer et al., 2015; Mckenzie et al., 2017; Cinar & Ozgul, 2023; Holt, 2024). In the UK, Didemnum vexillum has colonized Holyhead marina and Milford Haven, Wales; the west coast of Scotland (marinas around Largs, Clyde, Loch Creran and Loch Fyne), South Devon (Plymouth, Yealm, and Dartmouth estuaries), the Solent, northern Kent, Essex, and Suffolk coasts (Griffith et al., 2009; Lambert, 2009; Hitchin, 2012; Michin & Nunn, 2013; Bishop et al., 2015; Mckenzie et al., 2017; Tillin et al., 2020, Holt, 2024; NBN, 2024). Although a widespread invader, Didemnum vexillum has a limited ability for natural dispersal since the pelagic larvae remain in the water column for a short time (up to 36 hours). Therefore, it has a short dispersal phase that can allow the species to build localized populations (Herborg et al., 2009; Vercaemer et al., 2015; Holt, 2024). However, Bullard et al. (2007) suggested that Didemnum vexillum can form new colonies asexually by fragmentation. Colonies can produce long tendrils from an encrusting colony, which can fragment, disperse and settle, attaching to suitable hard substrata elsewhere (Bullard et al., 2007; Lambert, 2009; Stefaniak & Whitlatch, 2014). A fragmented colony can spread naturally for up to three weeks transported by ocean currents, attached to floating seaweed, seagrass or other floating biota, or as free-floating spherical colonies (Bullard et al., 2007; Lengyel et al., 2009; Stefaniak & Whitlatch, 2014; Holt, 2024). Fragments can reattach to suitable substrata within six hours of contact. Fragments have the potential to disperse around 20 km before reattachment (Lengyel et al., 2009). Valentine et al. (2007a) reported that colonies of Didemnum vexillum enlarged by 6 to 11 times by asexual budding after 15 days and enlarged 11 to 19 times after 30 days. Valentine et al. (2007a) concluded fragments could successfully grow, survive, and help to spread Didemnum vexillum. While natural fragmentation of tendrils is thought to allow Didemnum vexillum to invade longer distances and increase its dispersal potential, Stefaniak & Whitlatch (2014) found that only one tendril out of 80 reattached to the flat, bare substrata used in their study, because tendrils required an extensive (at least eight hour) period of contact to reattach. Stefaniak & Whitlatch (2014) suggested that once fragmented from a colony, the success of tendril reattachment was limited, and reattachment was not a major contributor to the invasive success of Didemnum vexillum. However, Stefaniak & Whitlatch (2014) also found that larvae-packed tendril fragments may increase natural dispersal distance, reproduction, and invasive success of Didemnum vexillum, and increase the distance larvae can travel. Not all colonies produce tendrils at all locations. Human-meditated transport via aquaculture facilities, boat hulls, commercial fishing vessels, and ballast water is probably the most important vector that has aided the long-distance dispersal of Didemnum vexillum and explains its prevalence in harbours and marinas (Bullard et al., 2007; Dijkstra et al., 2007; Griffith et al., 2009; Herborg et al., 2009). Fragmentation of colonies during transport or human disturbance (such as trawling or dredging) could indirectly disperse the species and enable it to find suitable conditions for establishment (Herborg et al., 2009). For example, in oyster farms in British Columbia, large fragments of Didemnum sp. come off oyster strings when they are pulled out of water and other fragments can be pulled off oysters and mussels and thrown back into the water, which is likely to aid dispersal of the invasive species (Bullard et al., 2007). Dijkstra et al. (2007) hypothesised that Didemnum sp. was introduced to the Gulf of Maine with oyster aquaculture in the Damariscotta River and transported via Pacific oysters. Didemnum vexillum was likely introduced into the UK from northern Europe or Ireland via poorly maintained or not antifouled vessels, movement of contaminated shellfish stock and aquaculture equipment, or via marine industries such as oil, gas, renewables, and dredging (Holt, 2024). Recent evidence from genetic material suggests that human-mediated dispersal, between marinas and shellfish culture sites, is the most likely pathway for connectivity of Didemnum vexillum populations throughout Ireland and Britain (Prentice et al., 2021; Holt, 2024). Didemnum vexillum can disperse away from artificial substrata, invading and colonizing natural substrata in surrounding areas (Tillin et al., 2020). Holt (2024) noted that Didemnum vexillum had not spread as far as feared in the UK since it was first recorded. The current evidence of Didemnum vexillum’s ability to spread on natural habitats in this area is sparse and often conflicting, complicated by genetics and its apparent variable habitat preferences and tolerances and its variable ability to adapt to ‘new’ conditions (Holt 2024). Didemnum vexillum has a seasonal growth cycle influenced by temperature (Valentine et al., 2007a). In warmer months (June and July) colonies may be large and well-developed encrusting mats. Populations experience more rapid growth from July to September sometimes continuing into December. Colonies begin to decline in health and ‘die-off’ when temperatures drop below 5°C during winter months from around October to April (Gittenberger, 2007; Valentine et al., 2007a; Herborg et al., 2009). Cold water months cause colonies to regress and reduce in size, yet they often regenerate as temperatures warm (Griffith et al., 2009; Kleeman, 2009, Mercer et al., 2009), although some populations may not survive winter at all (Dijkstra et al., 2007). The early growth phase, from May to July, is initiated by smaller colonies developing from remnants of colonies that survived the cold water (Valentine et al., 2007a). The seasonal growth cycle is also likely influenced by location. For example, the Didemnum sp. growth cycle for colonies in Sandwich tide pool (temperature range from -1°C to 24°C, with daily fluctuations), probably does not occur in deep offshore subtidal habitats in Georges Bank (annual temperature range from 4 °C to 15°C, and daily fluctuations are minimal) (Valentine et al., 2007a). Larval release and recruitment typically occur between 14 to 20°C and slow or cease below 9 to 11°C as summer ends (Griffith et al., 2009; Mckenzie et al., 2017). In New Zealand, recruitment occurs from November to July, where the highest average temperatures were recorded in February (18 to 22°C) and the lowest average temperatures were recorded in July (9 to 10°C) (Fletcher et al., 2013a). In this New Zealand study, higher water temperatures were associated with a higher level of recruitment (Fletcher et al., 2013a). Didemnum vexillum requires suitable hard substrata for successful settlement and the establishment of colonies. It can grow quickly and establish large colonies of dense encrusting mats on a variety of hard substrata (Valentine et al., 2007a; Griffith et al., 2009; Lambert, 2009; Groner et al., 2011; Cinar & Ozgul, 2023). Gittenberger (2007) stated that invasive Didemnum sp. was a threat to native ecosystems because of its ability to overgrow virtually all hard substrata present. Suitable hard substrata can include rocky substrata such as bedrock gravel, pebble, cobble, or boulders or artificial substrata such as a variety of maritime structures such as pontoons, docks, wood and metal pilings, chains, ropes and moorings, plastic and ship hulls and at aquaculture facilities (Valentine et al., 2007 a&b; Bullard et al., 2007; Griffith et al., 2009; Lambert, 2009; Tagliapietra et al., 2012; Tillin et al., 2020). Didemnum vexillum has been reported colonizing these types of hard substrata in the USA, Canada, northern Kent, and the Solent (Bullard et al., 2007; Valentine et al., 2007a; Valentine et al., 2007b; Hitchin, 2012; Vercaemer et al., 2015; Tillin et al., 2020). Didemnum vexillum has the ability to rapidly overgrow and displace on other sessile organisms such as other colonial ascidians (Ciona intestinalis, Styela clava, Ascidiella aspera, Botrylloides violaceus, Botryllus schlosseri, Diplosoma listerianium and Aplidium spp.), bryozoan, hydroids, sponges (Clione celata and Halichrondria sp.), anemone (Diadumene cincta), calcareous tube worms, eelgrass (Zostera marina), kelp (Laminaria spp. and Agarum sp.), green algae (Codium fragile subsp. fragile), red algae (Plocamium, Chondrus crispus and bush weed Agardhiella subulata), brown algae (Ascophyllum nodosum, Sargassum, Halidrys, Fucus evanescens and Fucus serratus), calcareous algae (Corallina officinalis), mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis, Perna canaliculus and Mytilus edulis), barnacles, oysters (Magallana gigas, Ostrea edulis and Crassostrea virginica), sea scallops (Placopecten magellanicus), or dead shells (Dijkstra et al., 2007; Gittenberger, 2007; Valentine et al., 2007a; Valentine et al., 2007b; Griffith et al., 2009; Carman & Grunden, 2010; Dijkstra & Nolan, 2011; Groner et al., 2011; Hitchin, 2012; Tagliapietra et al., 2012; Minchin & Nunn, 2013; Gittenberger et al., 2015; Long & Groholz, 2015; Vercaemer et al., 2015). In contrast to Didemnum vexillum’s preference for sheltered conditions, established colonies observed in Georges Bank and Long Island Sound were exposed to moderately strong tidal currents (1 to 2 knots; ca 0.5 to 1 m/s recorded at both sites) that may mobilise sediment (Valentine et al., 2007b; Mercer et al., 2009; Tillin et al., 2020). However, Valentine et al. (2007b) describe the substratum as immobile, presumably consolidated gravel, cobbles and pebbles. Kleeman (2009), stated that the presence of a consistent mild wave action or ‘swash zone’ appears to favour Didemnum sp. establishment in the intertidal. Although some evidence suggests that waves and currents can facilitate the fragmentation and spread of Didemnum vexillum (Mckenzie et al., 2017), the tidal current velocities at some sites where Didemnum vexillum has been reported (for example, New England, where current velocities reach up to around 3 m/s) is lower than the current velocity required for the dislodgement of Didemnum vexillum fragments (around 7.6 m/s) (Reinhardt et al., 2012). This suggests that not all tidal currents are likely to dislodge Didemnum vexillum fragments. When on boat hulls the species can experience higher current velocities which is enough to cause dislodgement (Reinhardt et al., 2012). Sensitivity assessment. If Undaria pinnatifida were to invade this biotope it may outcompete Sargassum. Hence, resistance to the pressure is assessed as ‘Low’, and resilience is ‘Very Low’. The sensitivity of this biotope to this pressure is assessed as ‘High’. It should be noted that due to the nature of this pressure, new INIS are constantly introduced. For this reason, evidence should be frequently revisited. Replacement of red algal turfs by other similar species may lead to some subtle effects on local ecology but at low abundances, the biotope would still be recognisable from the description. There is no evidence of Didmenum vexillum colonizing this biotope in the UK. Didemnum vexillum requires hard substrata for successful colonization, therefore, it could colonize the mixed substrata typical of this biotope. Didemnum vexillum prefers wave-sheltered conditions and can tolerate moderately strong tidal currents typical of this biotope. Also, Didemnum vexillum has been recorded in the lower intertidal. Didemnum vexillum can overgrow sessile organisms, including Sargassum sp. However, no evidence was found on how Didemnum vexillum affects Sargassum. Didemnum vexillum may compete for light and space with the macroalgae present in the biotope. This will potentially interfere with recruitment, which could lead to the mortality of some species and a reduction in biodiversity. Therefore, a resistance of 'Medium' (some mortality, <25%) is suggested as a precaution. Resilience is likely to be 'Very low' as Didemnum vexillum would need to be physically removed to allow recovery. Hence, sensitivity to invasion by Didemnum is assessed as 'Medium'. | LowHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Introduction of microbial pathogens [Show more]Introduction of microbial pathogensBenchmark. The introduction of relevant microbial pathogens or metazoan disease vectors to an area where they are currently not present (e.g. Martelia refringens and Bonamia, Avian influenza virus, viral Haemorrhagic Septicaemia virus). Further detail EvidenceLaminarians may be infected by the microscopic brown alga Streblonema aecidioides. Infected algae show symptoms of Streblonema disease, i.e. alterations of the blade and stipe ranging from dark spots to heavy deformations and completely crippled thalli. Infection can reduce growth rates of host algae (Peters & Scaffelke, 1996). The marine fungi Eurychasma spp can also infect early life stages of Laminarians however the effects of infection are unknown (Müller et al., 1999). Gracilaria gracilis is also susceptible to bacterial pathogens. Farmed and natural populations of Gracilaria gracilis within Saldanha Bay, South Africa have experienced a number of large die-offs since 1989. During these die backs thalli have become bleached and/or rotten as a result of Pseudoalteromonas gracilis B9 infection (Schroeder et al., 2003). No information can be found on the effect of microbial pathogens on Sargassum muticum or Ceramium virgatum. Sensitivity assessment. Resistance to the pressure at the benchmark is considered ‘Medium’ based on the potential susceptibility of two of the characterizing species. However, resilience is still assessed as ‘High’. The sensitivity of this biotope to introduction of microbial pathogens is assessed as ‘Low’ | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |