Littoral caves and overhangs

| Researched by | Dr Keith Hiscock | Refereed by | This information is not refereed |

|---|

Summary

UK and Ireland classification

Description

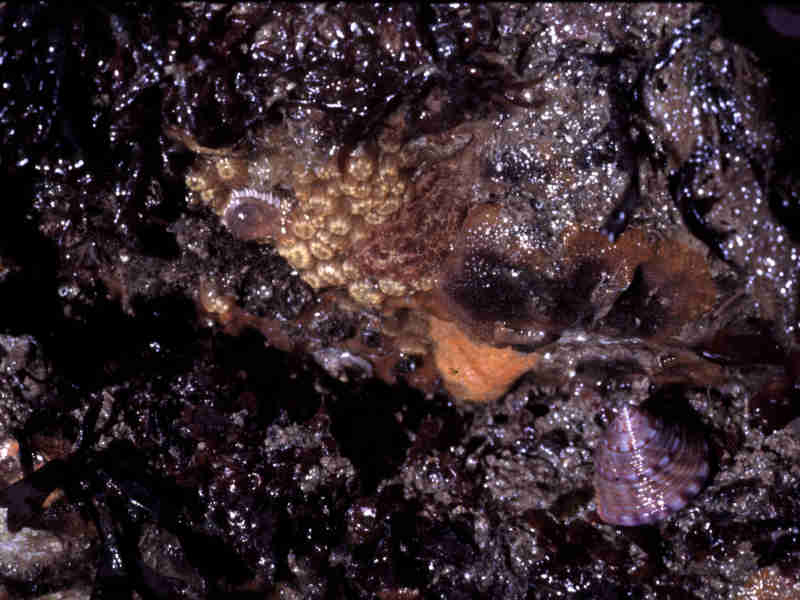

Where overhangs occur on rocky shores there is a reduction in desiccation which allows certain species to proliferate, in particular, crusts of bryozoans (for example, Umbonula littoralis), sponges (such as Halichondria panicea and Hymeniacidon perleve), ascidians (such as Botryllus schlosseri), barnacles (Perforatus perforatus in the south-west) and spirorbid tubeworms (SLR.SByAs). Erect bryozoans may occur such as species of Scrupocellaria and Bugula sp. Pendulous species such as the ascidian Morchellium argus and the fleshy bryozoan Alcyonidium diaphanum may also occur. Shade-tolerant red seaweeds can also grow in such conditions (SLR.SR). Mobile species that occur include the painted top shell Calliostoma zizyphinum, the cowrie, Trivia spp., the sting winkle Ocenebra erinacea and the cushion star Asterina gibbosa. On shady overhangs on the lowest shore, branching sponges such as Stelligera stuposa and corals (Caryophyllia smithii and sometimes Balanophyllia regia) may be found together with a range of sea anemone species. Adapted from Connor et al. (1997a).

Depth range

Upper shore, Mid shore, Lower shoreAdditional information

None

Listed By

Habitat review

Ecology

Ecological and functional relationships

Species living under overhangs are mainly active suspension feeders relying on water-borne food and are not generally interacting. However, overgrowth of one species by another may occur (cf. Turner, 1988) and some overhangs become dominated by one species especially Dendrodoa grossularia. A small number of species feed on the encrusting fauna including, for example, Doris pseudoargus on sponges, the cowrie Trivia monacha spp on compound ascidians, and the dog whelk Nucella lapillus on barnacles.Seasonal and longer term change

Changes are probably similar to those described by Foster-Smith (1989) for under-boulders where many encrusting ascidians increased in abundance by late summer on the Northumbrian coast.Habitat structure and complexity

Overhangs vary greatly in their 'openness' and their aspect. They can be deeply overhanging and be more like small shallow caves with downward facing surfaces to being almost vertical surfaces. Also, rock type is important in determining the community that develops. Where soft rock (for instance, limestone or chalk) is present there is likely to be a high proportion of boring species in the rock.Productivity

Not researchedRecruitment processes

Mainly from planktonic larvae.Time for community to reach maturity

Settlement panels, which attract similar communities to overhang habitats, may be fully colonized within about 18 months of being placed into the environment (extrapolated from Sutherland & Karlson 1977; Todd 1994). Development of 'mature' communities under overhangs is likely to occur within two years and there will be dynamic stability where the same species are always present but individuals and colonies die and recruit with time.Additional information

No studies were found that specifically describe overhang and intertidal cave communities.Preferences & Distribution

Habitat preferences

| Depth Range | Upper shore, Mid shore, Lower shore |

|---|---|

| Water clarity preferences | |

| Limiting Nutrients | Not relevant |

| Salinity preferences | Full (30-40 psu), Variable (18-40 psu) |

| Physiographic preferences | Open coast |

| Biological zone preferences | Eulittoral, Infralittoral |

| Substratum/habitat preferences | |

| Tidal strength preferences | |

| Wave exposure preferences | Exposed, Moderately exposed, Sheltered, Very exposed, Very sheltered |

| Other preferences | No text entered |

Additional Information

Overhanging surfaces and small caves occur especially where rocks are stratified and angled so that downward facing surfaces are present. Caves may form where basalt dykes erode and collapse amongst other harder igneous rocks. Soft rock such as chalk and limestone may also erode as a result of wave action to form caves. Cave habitats do not differ greatly in the communities present from those of overhangs or, on wave exposed coasts, surge gullies. Particularly well-developed examples of caves occur around Papa Stour in Shetland and St Kilda with intertidal cave habitats in chalk substrata especially well developed in Kent.Species composition

Species found especially in this biotope

Rare or scarce species associated with this biotope

-

Additional information

No text enteredSensitivity review

The MarLIN sensitivity assessment approach used below has been superseded by the MarESA (Marine Evidence-based Sensitivity Assessment) approach (see menu). The MarLIN approach was used for assessments from 1999-2010. The MarESA approach reflects the recent conservation imperatives and terminology and is used for sensitivity assessments from 2014 onwards.

Explanation

Overhang and cave communities are colonised especially by encrusting animal species. The species identified as indicative of sensitivity are characteristic species and represent species that, if lost from the biotope, it would no longer be that biotope.In undertaking this assessment of sensitivity, account is taken of knowledge of the biology of all characterizing species in the biotope. However, 'indicative species' are particularly important in undertaking the assessment because they have been subject to detailed research.

Species indicative of sensitivity

| Community Importance | Species name | Common Name |

| Important structural | Botryllus schlosseri | Star ascidian |

| Important characterizing | Morchellium argus | A compound ascidian |

| Important structural | Umbonula littoralis | An encrusting bryozoan |

Physical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Intolerance | Recoverability | Sensitivity | Species Richness | Evidence / Confidence | |

Substratum Loss [Show more]Removal of the substratum will remove the associated community. The majority of species characteristic of the community have planktonic larvae that are produced once a year so that settlement will be rapid. However, successional change will occur before the community reaches a dynamic stability similar to that before destruction.

| High | Moderate | Moderate | Major decline | Moderate |

Smothering [Show more]Smothering on overhangs and in caves is likely to occur as a result of overgrowth by dominating species (and not by siltation). Some overgrown species will survive (cf. Turner 1988) but a thick growth of Dendrodoa grossularia is likely to kill encrusting organisms below. Assuming that some living individuals remain and allowing for settlement of planktonic larvae, recovery is likely to be fairly rapid.

| High | High | Moderate | Decline | Low |

Increase in suspended sediment [Show more]The vertical and overhanging nature of surfaces means that siltation is unlikely to occur. Therefore, although component species may be highly intolerant of siltation, the biotope as a whole is not.

| Low | High | Low | Minor decline | Very low |

Decrease in suspended sediment [Show more] | |||||

Dessication [Show more]Species present under overhangs and in intertidal caves are emersed and subject to some drying for significant lengths of time and so withstand some desiccation. Changes of time immersed equivalent to one zonal height may not be significant providing that the communities are shaded. Recovery would occur from surviving colonies and individuals and new settlement from larval sources.

| Intermediate | High | Low | Minor decline | Low |

Increase in emergence regime [Show more]The main threat to species is if emersion time increases, in which case, intolerance is similar to that for desiccation, i.e. changes of time immersed equivalent to one zonal height may not be significant providing that the communities are shaded. However, during emersion they will be unable to feed so that some decline is probable. Recovery would occur from surviving colonies and individuals and new settlement from larval sources.

| Intermediate | High | Low | Minor decline | Low |

Decrease in emergence regime [Show more] | |||||

Increase in water flow rate [Show more]Where an overhang or cave is subject to flowing water (for instance, where it is in a tunnel or gully open at both ends), the character of the community is likely to change as species characteristic of stronger or weaker water flows predominate. However, many of the key characteristic species occur in a broad range of water flow types and the biotope will remain the same. Recovery would occur from surviving colonies and individuals and new settlement from larval sources.

| Intermediate | High | Low | No change | Low |

Decrease in water flow rate [Show more] | |||||

Increase in temperature [Show more]In the case of higher temperatures, some species that are predominantly sublittoral are likely to suffer higher rates of desiccation and drying. In the case of lower temperatures, some species may be subject to exposure to cold conditions although this is uncertain. Crisp (1964) recorded some adverse effects on compound ascidians in North Wales following the severe winter of 1962-63.

| Intermediate | High | Low | Minor decline | Low |

Decrease in temperature [Show more] | |||||

Increase in turbidity [Show more]The communities that occur under overhangs are similar in areas where high turbidity occurs (e.g. the entrance to estuaries) to those on the open coast, suggesting a tolerance to changing or different conditions of turbidity. Moore (1973b) found that Umbonula littoralis, one of the characterizing species, was ubiquitous in relation to a turbidity factor. Recovery would occur from surviving colonies and individuals and new settlement from larval sources.

| Low | High | Low | No change | Moderate |

Decrease in turbidity [Show more] | |||||

Increase in wave exposure [Show more]The communities that occur under overhangs are different on wave exposed and wave sheltered coasts - generally having a wider range of species on wave exposed sites compared to wave sheltered sites. However, many of the key characteristic species occur in a broad range of wave exposure types and the biotope is likely to remain the same even with a change of two exposure categories. Change in species richness has to be identified as "not relevant" because it is likely to increase with greater wave exposure and decrease with decline in wave exposure. Return to a previous species composition would occur from surviving colonies and individuals and new settlement from larval sources.

| Intermediate | High | Low | Not relevant | Low |

Decrease in wave exposure [Show more] | |||||

Noise [Show more]The characteristic species of the biotope are unlikely to detect noise.

| Tolerant | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant |

Visual Presence [Show more]The characteristic species of the biotope do not have visual organs and will not therefore detect visual presence.

| Tolerant | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant |

Abrasion & physical disturbance [Show more]Communities under overhangs and in caves which extend to a seabed that is of mobile substrata demonstrate a zonation from bare (abraded) rock adjacent to the bottom, through fast settling and growing species to abrasion tolerant species to the typical overhang community (that is nevertheless probably subject to abrasion and damage during storms). Whilst whole communities are destroyed by abrasion from coarse sediments including especially pebbles and cobbles, recovery would occur from surviving colonies and individuals and new settlement from larval sources. Abrasion by human activities might include anchoring and dredging (fisheries).

| High | High | Moderate | Major decline | High |

Displacement [Show more]The most important species in characterizing this community are sessile and will be unable to reattach and killed if displaced. Recovery would occur from surviving colonies and individuals and new settlement from larval sources.

| High | High | Moderate | Major decline | Moderate |

Chemical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Intolerance | Recoverability | Sensitivity | Richness | Evidence / Confidence | |

Synthetic compound contamination [Show more]Most sessile invertebrates have not been shown to have a high susceptibility to synthetic chemicals such as anti-fouling compounds. However, some mobile species that are a part of the community, such as Ocenebra erinacea and Nucella lapillus (Gibbs et al. 1990 & 1991) have been shown to be intolerant of some synthetic chemicals. More difficult-to-detect effects may occur to larval stages of a wide range of the species that occur under overhangs. The species of mollusc that have been shown to be adversely affected lay eggs on the shore and have a short or no planktonic phase so that recovery of those minority of species will be slow.

| Intermediate | Low | High | Minor decline | Low |

Heavy metal contamination [Show more]Insufficient

information. | No information | Not relevant | No information | Not relevant | Not relevant |

Hydrocarbon contamination [Show more]Ryland & de Putron (1998) found no detectable damage to under-boulder communities, which are similar to some overhang communities, in Watwick Bay, Pembrokeshire following the Sea Empress oil spill. Part of the resistance to effects might be because oil does not settle onto overhanging surfaces. However, some species, especially gastropods are likely to be narcotised and killed and some damage is likely. Return to a previous species composition would occur from new settlement from larval sources although some gastropods have no or only a short dispersal phase so that recovery will be slow.

| Low | Moderate | Low | Minor decline | Low |

Radionuclide contamination [Show more]Insufficient

information. | No information | Not relevant | No information | Not relevant | Not relevant |

Changes in nutrient levels [Show more]Similar overhang communities occur where nutrient levels are high (for instance at the entrance to estuaries) or normal (near to the open coast).

| Tolerant | Not relevant | Not relevant | No change | Low |

Increase in salinity [Show more]Overhang communities occurring near to the entrance to estuaries are probably subject to occasional lowered salinity and so appear tolerant of some reduction in salinity at least for short periods. However, some species characteristic of overhangs on the open coast do not extend into estuaries whilst the sea squirt Dendrodoa grossularia often becomes dominant into conditions of variable or low salinity. Thus change is likely to occur if salinity is lowered for a significant length of time (the benchmark is one salinity grade for one year). Recovery would occur from surviving colonies and individuals and new settlement from larval sources.

| Intermediate | High | Low | Decline | Low |

Decrease in salinity [Show more] | |||||

Changes in oxygenation [Show more]Decaying marine life may be observed in the areas of overhangs and caves most sheltered from water movement. The species characteristic of the community therefore do seem to be adversely affected by de-oxygenation. Recovery would occur from surviving colonies and individuals and new settlement from larval sources.

| High | High | Moderate | Decline | Low |

Biological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Intolerance | Recoverability | Sensitivity | Richness | Evidence / Confidence | |

Introduction of microbial pathogens/parasites [Show more]Insufficient

information. | No information | Not relevant | No information | Not relevant | Not relevant |

Introduction of non-native species [Show more]Any effects are dependant on the biology of the non-native species. Whilst those non-native species currently present in Britain and Ireland have not been observed to significantly affect overhang or cave biotopes, effects of future imports are unpredictable.

| No information | Not relevant | No information | Insufficient information |

Not relevant |

Extraction of this species [Show more]Crabs (Cancer pagurus) and lobster (Homarus gammarus) are taken from deep recesses at the backs of overhangs often using a metal hook. However, none of the species indicative of sensitivity are likely to be extracted and the removal of these crustaceans will not affect the recognisable biotope. Not relevant has been suggested.

| Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant |

Extraction of other species [Show more] | Intermediate | High | Low | Minor decline | Very low |

Additional information

-

Bibliography

Connor, D.W., Brazier, D.P., Hill, T.O., & Northen, K.O., 1997b. Marine biotope classification for Britain and Ireland. Vol. 1. Littoral biotopes. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough, JNCC Report no. 229, Version 97.06., Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough, JNCC Report No. 230, Version 97.06.

Connor, D.W., Dalkin, M.J., Hill, T.O., Holt, R.H.F. & Sanderson, W.G., 1997a. Marine biotope classification for Britain and Ireland. Vol. 2. Sublittoral biotopes. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough, JNCC Report no. 230, Version 97.06., Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough, JNCC Report no. 230, Version 97.06.

Crisp, D.J. (ed.), 1964. The effects of the severe winter of 1962-63 on marine life in Britain. Journal of Animal Ecology, 33, 165-210.

Foster-Smith, R.L., 1989. A survey of boulder habitats on the Northumberland coast with a discussion on survey methods for boulder habitats. Nature Conservancy Council, Peterborough, unpub. NCC CSD Rep. 921, 76pp.

Foster-Smith, R.L., & Foster-Smith, J.L., 1987. A marine biological survey of Beadnell to Dunstanburgh Castle, Northumberland (a contribution to the Marine Nature Conservation Review). Nature Conservancy Council, Peterborough, unpub. NCC CSD Rep. 798, 82pp.

Gibbs, P., Bryan, G, & Spence, S., 1991. The impact of tributyltin (TBT) pollution on Nucella lapillus (Gastropoda) populations around the coast of south-east England. Oceanologica Acta, Special Issue, 11, 257-261.

Gibbs, P.E., Bryan, G.W., Pasco, P.l., & Burt, G.R., 1990. Reproductive abnormalities in female Ocenebra erinacea (Gastropoda) resulting from tributyltin-induced imposex. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 70, 639-656.

JNCC (Joint Nature Conservation Committee), 2022. The Marine Habitat Classification for Britain and Ireland Version 22.04. [Date accessed]. Available from: https://mhc.jncc.gov.uk/

Moore, P.G., 1973b. The kelp fauna of north east Britain. II. Multivariate classification: turbidity as an ecological factor. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 13, 127-163.

Sutherland, J.P. & Karlson, R.H., 1977. Development and stability of the fouling community at Beaufort, North Carolina. Ecological Monographs, 47, 425-446.

Todd, C.D., 1994. Competition for space in encrusting bryozoan assemblages: the influence of encounter angle, site and year. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 74, 603-622.

Turner, S.J., 1988. Ecology of intertidal and sublittoral cryptic epifaunal assemblages. II. Non-lethal overgrowth of encrusting bryozoans by colonial tunicates. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 115, 113-126.

Citation

This review can be cited as:

Last Updated: 23/11/2002