Arenicola marina in infralittoral mud

| Researched by | Dr Harvey Tyler-Walters | Refereed by | This information is not refereed |

|---|

Summary

UK and Ireland classification

Description

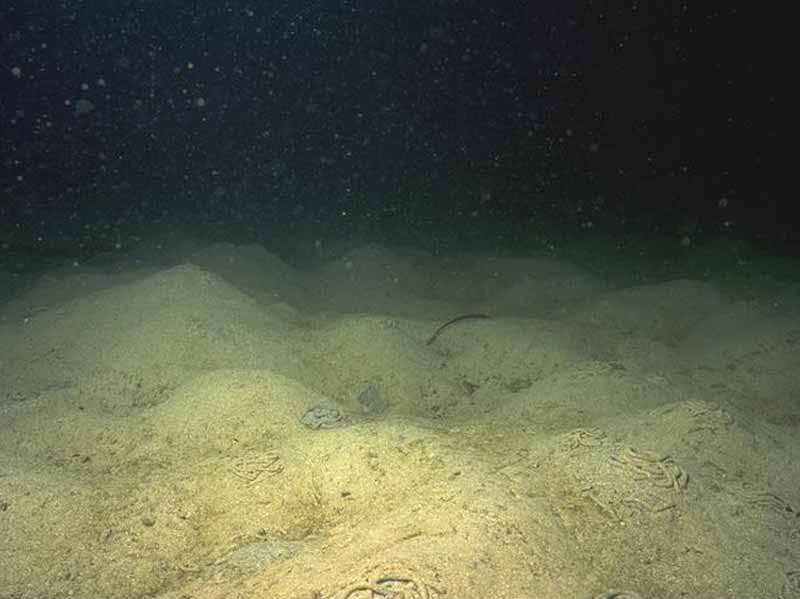

In very shallow, extremely sheltered, very soft muds Arenicola marina may form very conspicuous mounds and casts. This biotope may also contain synaptid holothurians such as Labidoplax media and Leptosynapta bergensis or L. inhaerens. However, these species may be under recorded (possibly due to periodicity in feeding) and are not considered characteristic of this biotope. Other conspicuous fauna may include Carcinus maenas, Asterias rubens and Pagurus bernhardus whilst the scallop Pecten maximus and the turret shell Turritellinella tricarinata may also be present in some areas. This biotope typically occurs in waters shallower than about 5 m in sheltered basins of sea lochs and lagoons that may be partially separated from the open sea by tidal narrows or rapids. Sediment surfaces may become covered by a diatom film at certain times of the year. (Information from JNCC, 2022).

Depth range

0-5 m, 5-10 mAdditional information

No text entered

Listed By

Habitat review

Ecology

Ecological and functional relationships

The ecology of this biotope is assumed to be similar to that of most muddy habitats.

- Sheltered areas accumulate fine muds and silts, which in turn accumulate organic material in the form of detritus from the surrounding habits (e.g. from settling phytoplankton, plants and macroalgae) and from the surrounding catchment area via riverine or pluvial water flow (Elliot et al., 1998).

- Fine muds and silts adsorb organic material and provide a large surface area for microbial colonization by heterotrophic microbes that degrade organic matter. However, the fine silts and muds result in low permeability, trapping detritus, and the large microbial population leads to high oxygen uptake, deoxygenation of the sediment and low degradation rates. Therefore, fine muds accumulate organic matter (Elliot et al., 1998).

- Deoxygenation results in anaerobic degradation (releasing hydrogen sulphide, methane and ammonia) in the deeper sediment but release dissolved organic matter and nutrients for consumption by the aerobic microbes living at the surface (Elliot et al., 1998).

- The large surface area of the particulates support microflora (microphytobenthos), such as diatoms and euglenoids, and this biotope may be covered by a diatom film (Connor et al., 1997a; Elliot et al., 1998).

- The mud surface may be covered by ephemeral green algae such as Derbesia sp. (JNCC, 1999).

- The majority of the macrofauna are deposit feeders that consume meiofauna, organic detritus, bacteria and microphytobenthos (e.g. diatoms) in the sediment.

- Arenicola marina and Leptosynapta sp. are 'funnel feeding' surface deposit feeders, ingesting sediment from the base of a funnel of sediment from within a U-shaped burrow (see Arenicola marina review; Hyman, 1955; Wells, 1945; Lawrence, 1987; Massin, 1982a, 1982b; Zebe & Schiedek, 1996).

- Labidoplax media lives in the first few centimetres of sediment, ingesting sediment particles picked up by its tentacles (Gotto & Gotto, 1972). Where present, terebellids feed on surface deposits.

- Arenicola marina and holothurians are known to take up dissolved organic matter (DOM).

- Mobile species are opportunistic scavengers and predators and include starfish (e.g. Asterias rubens), crabs and hermit crabs (e.g. Carcinus maenas and Pagurus bernhardus), flatfish and gobies (e.g. Pomatoschistus minutus). Flatfish are important predators on intertidal mudflats and are presumably of similar importance in this biotope taking individual Labidoplax sp., Leptosynapta sp. and polychaetes.

- Flatfish are known to 'nip' the tails of Arenicola marina.

- This is a shallow (0-5 m) biotope and some predation from wading birds and wildfowl probably occurs, although no information was found.

Barnes (1980) provides a generalised food web for lagoonal habitats, which may be similar to the food web expected within this biotope.

Seasonal and longer term change

Microphytobenthos and algal production may increase in spring, resulting in the formation of mats of ephemeral algae, and be reduced in winter. High summer temperatures may increase the microbial activity resulting in deoxygenation (hypoxia or anoxia), or alternatively, result in thermoclines in shallow bays and resultant hypoxia of in the near bottom water (Hayward, 1994; Elliot et al., 1998). Flatfish and crabs often migrate to deeper water in the winter months, and therefore, predation pressure may be reduced in this biotope. Mud habitats of sheltered areas are relatively stable habitats, however especially cold winter or hot summers could adversely affect the macrofauna (see sensitivity). In addition, extreme freshwater runoff resulting from heavy rains and storms may result in low salinity conditions. No information on long-term change was found.

Habitat structure and complexity

Sheltered sediments, (such as found in this biotope) are characterized by fine grain size, low porosity, generally low permeability (and hence high water content), high sediment stability (due to cohesion), a low oxygen content and highly reducing conditions (Elliot et al., 1998). The mud surface is oxygenated. However, in fine muds, the anoxic reducing layer is likely to be very close to the surface, often less than 1 cm (Elliot et al., 1998). Bioturbation by burrowing species, especially Arenicola marina and to a lesser extent Leptosynapta sp. results in mobilisation of the sediment and nutrients from deeper sediment to the surface, making nutrients available to surface dwelling organisms. In addition, continued irrigation of their burrows by Arenicola marina and Leptosynata sp. transports oxygenated water into the sediment, resulting in oxygenated micro-environments in the vicinity of their burrows.

In high enough abundances bioturbation by Arenicola marina (and to a lesser extent Leptosynapta sp.) modifies the sediment surface into mounds or casts and funnels. The resultant increase in bed roughness may result in increased susceptibility to erosion since raised features provide sites where areas of turbulent flow can be initiated. However, the effects of mucus binding in faecal pellet deposits increase the cohesiveness of the sediment, reducing its susceptibility to erosion (see Hall, 1994). For example, Leptosynapta tenuis was reported to increase the stability of the upper 3 cm of sediment, while decreasing the stability of sediment below 3-10 cm (Massin, 1982b). In addition, pits may capture fine detritus, resulting in increase microbial production within the pit. Surface sediment cohesion is also increased by the mucus binding of diatoms, bacteria and meiofauna (Hall, 1994).

The habitat can be divided into the following niches:

- a mobile epifauna of scavengers and opportunistic predators;

- a sediment surface of ephemeral green algae in the summer months;

- a sediment surface flora of microalgae such as diatoms and euglenoids, together with aerobic microbes;

- an aerobic upper layer of sediment (depth depending on local conditions but possibly <1cm) supporting shallow burrowing species such as Labidoplax media or Labidoplax buskii;

- a reducing layer and a deeper anoxic layer supporting chemoautotrophic bacteria, and

- burrowing polychaetes (e.g. terebellids and Arenicola marina) and burrowing synaptids (e.g. Leptosynapta sp.) that can irrigate their burrows.

Productivity

Primary productivity is provided by microphytobenthos, epifloral algae and settling phytoplankton. However, the majority of productivity will be secondary, from the consumption of detritus and other organic material. Microbial degradation of detritus makes primary production readily available for animal consumption (McLusky, 1989; Elliot et al., 1998). No information concerning overall productivity in this biotope was found.

Recruitment processes

Sessile or sedentary species in the biotope recruit from planktonic propagules (larvae and spores).

Arenicola marina has a high fecundity and spawns synchronously within a given area, although the spawning period varies between areas. Spawning usually coincides with spring tides and fair weather (high pressure, low rainfall and wind speed) (see Arenicola marina review). Beukema & de Vlas, (1979) suggested an average annual mortality or 22%, an annual recruitment of 20% and reported that the abundance of the population had been stable for the previous 10 years. However, Newell (1948) reported 40% mortality of adults after spawning in Whitstable. McLusky et al. (1983) examined the effects of bait digging on blow lug populations in the Forth estuary. Recovery occurred within a few months by recolonization from surrounding sediment (Fowler, 1999). Beukema (1995) noted that the lugworm stock recovered slowly from mechanical dredging reaching its original level in at least three years.

Overall, therefore recovery is generally regarded as rapid, and occur by recolonization by adults or colonization by juveniles from adjacent populations. However, Fowler (1999) pointed out that recovery may take longer on a small pocket, isolated, beach with limited possibility of recolonization from surrounding areas. Therefore, if adjacent populations are available recovery will be rapid. However, where the affected population is isolated or severely reduced (e.g. by long-term mechanical dredging), then recovery may be extended. taking up to 5 years.

Little information concerning reproduction and recruitment in synaptid holothurians was found. Recruitment is echinoderms shows both temporal and spatial variability and is often sporadic and unpredictable. The role of pelagic predators and post settlement mortality is poorly understood (see Ebert, 1983 and Smiley et al., 1991 for reviews).

Labidoplax sp. and Leptosynapta sp. are hermaphrodites. For example, in Labidoplax buskii, male and female gametes are spawned on different days, presumably with some chemical mediated synchrony (Nyholm, 1951). Eggs are shed and sink to the sediment surface. Development is direct and lecithotrophic, forming a free swimming gastrula after about 2 days. Larvae are pelagic for 10-12 days, forming a pentactula larvae, returning to the sediment surface after 11-14 days in the laboratory (Nyholm, 1951). Nyholm (1951) stated that juveniles grew rapidly in their first 2 months of benthic life, reaching sexual maturity after 1 yr. In the Gullmar Fjord, the breeding season was between October to January, within a maximum in November and December (Nyholm, 1951). Nyholm (1951) considered the dispersal to be 'good'. Gotto & Gotto (1972) reported an increase in gonadial development in spring and summer in Labidoplax media from Strangford Lough, Ireland but observed only eggs and suggested that it was a protandrous hermaphrodite. Leptosynapta inhaerens was reported to breed between August and September in Norway (Smiley et al., 1991).

Although, the pelagic nature of propagules provide a potential for good dispersal, this biotope is found in particularly sheltered environments with limited water flow. Therefore, populations may be self recruiting and should a population be severely reduced it may take some time for recolonization to occur from other populations.

Time for community to reach maturity

No information concerning community development was found. However, it is likely to depend on the species present, the hydrographic regime and recruitment and is likely to be highly variable between locations (see above).

Additional information

No text entered

Preferences & Distribution

Habitat preferences

| Depth Range | 0-5 m, 5-10 m |

|---|---|

| Water clarity preferences | No information |

| Limiting Nutrients | No information |

| Salinity preferences | Full (30-40 psu) |

| Physiographic preferences | Enclosed coast or Embayment |

| Biological zone preferences | Infralittoral |

| Substratum/habitat preferences | Mud |

| Tidal strength preferences | Very weak (negligible), Weak < 1 knot (<0.5 m/sec.) |

| Wave exposure preferences | Extremely sheltered, Very sheltered |

| Other preferences |

Additional Information

This biotope is restricted to very or extremely sheltered conditions with weak or very weak water flow, It was also recorded from the extremely wave sheltered lagoon in Neavag Bay (Thorpe et al., 1998) and the ultra-sheltered lagoon, the Houb, Fora Ness, Shetland (Thorpe, 1998).

Species composition

Species found especially in this biotope

- Arenicola marina

- Labidoplax media

- Leptosynapta bergensis

Rare or scarce species associated with this biotope

-

Additional information

The MNCR recorded 292 species within this biotope, although not all are present in each instance of the biotope (JNCC, 1999).Sensitivity review

Sensitivity characteristics of the habitat and relevant characteristic species

Arenicola marina and Leptosynapta sp. are 'funnel feeding' surface deposit feeders, ingesting sediment from the base of a funnel of sediment from within a U-shaped burrow (see Arenicola marina review; Hyman, 1955; Wells, 1945; Lawrence, 1987; Massin, 1982a, 1982b; Zebe & Schiedek, 1996). Bioturbation by burrowing species, especially Arenicola marina and to a lesser extent Leptosynapta sp. results in mobilisation of the sediment and nutrients from deeper sediment to the surface, making nutrients available to surface dwelling organisms. In addition, continued irrigation of their burrows by Arenicola marina and Leptosynata sp. transports oxygenated water into the sediment, resulting in oxygenated micro-environments in the vicinity of their burrows.

In high enough abundances, bioturbation by Arenicola marina (and to a lesser extent Leptosynapta sp.) modifies the sediment surface into mounds of casts and funnels. The resultant increase in bed roughness may result in increased susceptibility to erosion since raised features provide sites where areas of turbulent flow can be initiated. However, the effects of mucus binding in faecal pellet deposits increase the cohesiveness of the sediment, reducing its susceptibility to erosion (see Hall, 1994). Wendelboe et al. (2013) noted that sediment reworking by Arenicola marina (in mesocosms) increased the volume of sediment exposed to hydrodynamic flow and, hence, the resuspension of fine particulate and organic matter, depending on water flow, in the sediment to a depth of >20 cm. Also, Leptosynapta tenuis was reported to increase the stability of the upper 3 cm of sediment, while decreasing the stability of sediment below 3-10 cm (Massin, 1982b). In addition, pits may capture fine detritus, resulting in increase microbial production within the pit. Therefore, bioturbation by both Arenicola marina and Leptosynapta sp. can modify the sediment characteristics, its organic content, and surface profile.

Arenicola marina is the only important characterizing species within the biotope and a loss in the abundance of its population would result in loss or reclassification of the biotope. The synaptid holothurians (Leptosynapta and Labidoplax) are under recorded and not considered characterizing (Connor et al., 2004). Similarly, the remaining species are mobile and/or only recorded as present, and are probably found on similar sediments in the surrounding area. Therefore, the sensitivity of the biotope is dependent on the sensitivity of the population of Arenicola marina.

Resilience and recovery rates of habitat

Arenicola marina has a high fecundity and spawns synchronously within a given area, although the spawning period varies between areas. Spawning usually coincides with spring tides and fair weather (high pressure, low rainfall and wind speed) (see Arenicola marina review).Wilde & Berghuis (1979b) reported 316,000 oocytes per female with an average wet weight of 4 grammes. Eggs and early larvae develop within the female burrow. Post-larvae are capable of active migration by crawling, swimming in the water column and passive transport by currents (Farke & Berghuis, 1979) e.g. Günther (1992) suggested that post-larvae of Arenicola marina were transported distances in the range of 1 km. Juvenile settlement is density dependent and the juveniles avoid areas of high adult abundance and settle above the adults on the shore (Farke & Berghuis, 1979; Reise et al., 2001). For example, on the sand flat of Sylt (North Sea), post-larvae hibernate in mussel beds and shell gravel in deep tidal channels, then migrate above the normal adult range (towards the top of the shore) and settle in conspicuous nursery beds in May to October. The juveniles migrate down the shore before or during the next winter, leaving the upper shore for the next generation. Reise et al. (2001) suggested that the largest and possibly oldest individuals were found seaward and in subtidal sands.

Adults reach sexual maturity by their second year (Newell, 1948; Wilde & Berghuis, 1979) but may mature by the end of their first year in favourable conditions depending on temperature, body size, and hence food availability (Wilde & Berghuis, 1979). Beukema & de Vlas, (1979) suggested a lifespan, in the Dutch Wadden Sea, of at least 5-6 years, and cite a lifespan of at least 6 years in aquaria. They also suggested an average annual mortality or 22%, an annual recruitment of 20% and reported that the abundance of the population had been stable for the previous 10 years. However, Newell (1948) reported 40% mortality of adults after spawning in Whitstable.

McLusky et al. (1983) examined the effects of bait digging on blow lug populations in the Forth estuary. Dug and in-filled areas and unfilled basins left after digging re-populated within 1 month, whereas mounds of dug sediment took longer and showed a reduced population. Basins accumulated fine sediment and organic matter and showed increased population levels for about 2-3 months after digging. Beukema (1995) noted that the lugworm stock recovered slowly from mechanical dredging reaching its original level in at least three years. Reise et al. (2001) noted that a 50% reduction in the abundance of adult lugworm on sand flats in Sylt after the severe winter of 1995/96, was replaced by an enhanced recruitment of juveniles in spring, so that the effect of the severe winter on Arenicola marina population was small and brief. Beukema (1995) estimated that four to five years of mechanical dredging in the Balgzand region of the Wadden Sea, increased the mortality of the Arenicola population by ca 17% per year to a total of ca 40% per year and resulted in a long-term decline in the lugworm stock, until the dredge moved to a richer area. However, Beukema (1995) noted that the lugworm stock recovered slowly after mechanical dredging, reaching its original level after at least three years.

Therefore, the recovery of Arenicola marina populations is generally regarded as rapid and occurs by recolonization by adults or colonization by juveniles from adjacent populations or the subtidal. However, Fowler (1999) pointed out that recovery may take longer on a small pocket, isolated, beach with limited possibility of recolonization from surrounding areas. Therefore, if adjacent populations are available recovery will be rapid. However, where the affected population is isolated or severely reduced (e.g. by long-term mechanical dredging), then recovery may be extended.

Little information concerning reproduction and recruitment in synaptid holothurians was found. Recruitment in echinoderms shows both temporal and spatial variability and is often sporadic and unpredictable. The role of pelagic predators and post-settlement mortality is poorly understood (see Ebert, 1983 and Smiley et al., 1991 for reviews).

Labidoplax sp. and Leptosynapta sp. are hermaphrodites. For example, in Labidoplax buskii, male and female gametes are spawned on different days, presumably with some chemical mediated synchrony (Nyholm, 1951). Eggs are shed and sink to the sediment surface. Development is direct and lecithotrophic, forming a free swimming gastrula after about 2 days. Larvae are pelagic for 10-12 days, forming a pentactula larvae, returning to the sediment surface after 11-14 days in the laboratory (Nyholm, 1951). Nyholm (1951) stated that juveniles grew rapidly in their first 2 months of benthic life, reaching sexual maturity after 1 yr. In the Gullmar Fjord, the breeding season was between October to January, within a maximum in November and December (Nyholm, 1951). Nyholm (1951) considered the dispersal to be 'good'. Gotto & Gotto (1972) reported an increase in gonadial development in spring and summer in Labidoplax media from Strangford Lough, Ireland but observed only eggs and suggested that it was a protandrous hermaphrodite. Leptosynapta inhaerens was reported to breed between August and September in Norway (Smiley et al., 1991).

Resilience assessment. Overall, the recovery of Arenicola marina is probably rapid and holothurians recruitment is also potentially good but sporadic. However, this biotope is found in particularly sheltered environments with limited water flow typically sheltered basins of sea lochs and lagoons that may be partially separated from the open sea by tidal narrows or rapids (Connor et al., 2004). The Arenicola marina and holothurians populations may be self-recruiting and recovery from some mortality may be rapid. However, should a population be severely reduced it may take some time for recolonization to occur from other populations. Therefore, where resistance is ‘Medium’ (some mortality) a resilience of High is recorded but where resistance is lower (‘Low’ to ‘None’; significant mortality) a resilience of Medium (2-10 years) is recorded, to represent the isolated waters in which this biotope is found.

Hydrological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Temperature increase (local) [Show more]Temperature increase (local)Benchmark. A 5°C increase in temperature for one month, or 2°C for one year. Further detail EvidenceArenicola marina is recorded from shores of western Europe, Norway, Spitzbergen, north Siberia, and Iceland. In the western Atlantic, it has been recorded from Greenland, along the northern coast from the Bay of Fundy to Long Island. Its southern limit is about 40°N (see Arenicola marina review), although OBIS (2016) includes a few records from the Atlantic coast of Africa and the Mediterranean. Sommer et al. (1997) examined sub-lethal effects of temperature in Arenicola marina and suggested a critical upper and lower temperature of 20°C and 5°C respectively in North Sea specimens. Above or below these critical temperatures, specimens resort to anaerobic respiration. Sommer et al. (1997) noted that specimens could not acclimate to a 4°C increase above the critical temperature. De Wilde & Berghuis (1979) reported 20% mortality of juveniles reared at 5°C, negligible mortality at 10 and 15°C but 50% mortality at 20°C and 90% at 25°C. Schroeer et al. (2009) identified a shift in the thermal tolerance of Arenicola marina, with an optimum moving towards higher temperatures with decreasing latitudes, suggesting the species may adapt to long-term shifts such as 2°C but over time. Therefore, Arenicola marina in UK and Irish populations will occupy an optimum temperature range in relation to UK and Irish latitudes. An upper limit above 20°C may occur in more southerly populations. In studies in Whitley Bay, Tyne and Wear, UK, Arenicola marina was most active in spring and summer months, with a mean rate of cast production fastest in spring and particularly slow in autumn and winter, suggesting feeding rate is greatest in higher temperatures (Retraubun et al., 1996). Retraubun et al. (1996) also showed that cast production by specimens in lab experiments increased with temperature, peaking at 20°C before declining. Rates of cast production at 30°C were still higher than at 10°C, suggesting UK populations may have greater tolerance to higher temperatures than populations studied in more northerly latitudes. Temperature change may affect maturation, spawning time and synchronisation of spawning and reproduction in the long-term (Bentley & Pacey, 1992; Watson et al., 2000). Spawning can be inhibited in gravid adults maintained above 15°C (Watson et al., 2000). However, spawning success would remain dependent upon spring and autumn temperatures remaining below 15°C. Additionally, an impact from temperature change at the substratum surface may be mitigated as Arenicola marina is protected from direct effects by their position in the sediment. Little information was found concerning temperature tolerance in synaptid holothurians. Both Labidoplax media and Leptosynapta bergensis are essentially boreal species, being restricted to the northern shores of the British Isles. Therefore, these species may be intolerant of increase of temperature, especially short-term acute change. Sensitivity assessment. Arenicola marina is probably not resistant of a short-term acute change in temperature of 5°C, although it is unlikely to be directly affected due to its infaunal habit and can migrate down the shore to deeper waters to avoid the changes in temperature (Reise et al., 2001). Hence, a resistance of Medium is suggested to represent a loss of some of the Arenicola population and especially juveniles, and a proportion of the synaptid holothurians. Resilience is probably High and sensitivity is assessed as Low. | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Temperature decrease (local) [Show more]Temperature decrease (local)Benchmark. A 5°C decrease in temperature for one month, or 2°C for one year. Further detail EvidenceArenicola marina is recorded from shores of western Europe, Norway, Spitzbergen, north Siberia, and Iceland. In the western Atlantic, it has been recorded from Greenland, along the northern coast from the Bay of Fundy to Long Island. Its southern limit is about 40°N (see Arenicola marina review), although OBIS (2016) includes a few records from the Atlantic coast of Africa and the Mediterranean. Arenicola marina displays a greater tolerance to decreases in temperature than to increases, although optimum temperatures are reported to be between 5°C and 20°C. Reise et al. (2001) stated that Arenicola marina was known to be a winter hardy species and that its abundance and biomass were stable even after severe winters. Sommer et al. (1997) report populations in the White Sea (sub-polar) acclimatised to -2°C in winter. Populations in the North Sea (boreal) were less tolerant of temperatures below 5°C, although in laboratory experiments on individual lugworms from North Sea populations worms survived a temperature drop from 6 or 12°C to -1.7°C for more than a week (Sommer & Portner, 1999). Temperature change may affect maturation, spawning time and synchronisation of spawning and reproduction in the long-term (Bentley & Pacey, 1992; Watson et al., 2000). Spawning success is dependent upon spring and autumn temperatures, the seasons when spawning occurs in relation to spring and neap tides, remaining below 13-15°C. De Wilde & Berghuis (1979) reported 20% mortality of juveniles reared at 5 °C, negligible mortality at 10 °C and 15 °C but 50% at 20°C and 90% mortality at 25°C. Evidence from the Sylt in the North Sea suggests that the effects of severe winters on Arenicola marina populations are small and brief (Reise, et al., 2001) The severe winter of 1995/1996 disrupted the usual juvenile settlement cycle in the sand flats of the Sylt, North Sea (Reise et al., 2001). In the severe winter, the adult population of Arenicola marina migrated down the shore, to deeper, waters to avoid low temperatures and 66 days of ice on the intertidal sand flats. Although, the adult population was halved, and no dead lugworms were observed on the surface or in the sediment. The post-larvae hibernate in the deep water channels (subtidal) in shell gravel and mussel beds. In summer the juveniles were not restricted to the upper shore but settled over a wider area of the flats, in the space left by the adult population. Reise et al. (2001) concluded that the enhanced recruitment demonstrated that the post-larvae did not suffer increased mortality during the winter, probably as their subtidal hibernation sites did not experience ice cover. Similarly, Arenicola marina was listed as ‘apparently unaffected’ by the severe 1962/63 winter in the UK (Crisp, 1964). Little information was found regarding temperature tolerance in synaptid holothurians. Both Labidoplax media and Leptosynapta bergensis are essentially boreal in distribution being essentially limited in distribution to northern habitats in the British Isles and may not be affected by a long-term decrease in temperature. The shallow, enclosed situations they are found in are subject to significant decreases in temperature driven by air temperatures because of their enclosed site. Therefore, they may be resistant of sharp decreases in temperature. Sensitivity assessment. Arenicola marina populations are distributed to the north of the British Isles, exhibit regional acclimation to temperature, are known to be winter hardy, and can migrate to deeper water to avoid change in temperature and even ice. The synaptid holothurians are boreal species. Therefore, the biotope is probably resistant of a short to long-term decrease in temperature at the benchmark level and a resistance of High is suggested. Hence, resilience is High and the biotope is assessed as Not sensitive at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Salinity increase (local) [Show more]Salinity increase (local)Benchmark. A increase in one MNCR salinity category above the usual range of the biotope or habitat. Further detail EvidenceThe biotope occurs in ‘full’ (35 ppt) salinity so that in an increase in salinity would result in hypersaline conditions (>40 ppt). Hypersaline conditions are only likely because of hypersaline effluents (brines). Arenicola marina loses weight when exposed to hyperosmotic shock (47 psu for 24 hrs) but are able to regulate and gain weight within 7-10 days (Zebe & Schiedek, 1996). Echinoderms are generally regarded as stenohaline and most species are exclusively marine (Binyon, 1966; Pawson, 1966; Stickle & Diehl, 1987; Lawrence, 1996; Russell, 2013). Leptosynapta inhaerens was reported to be euryhaline but only known in full salinity waters in European waters (Binyon, 1966) while Leptosynapta chela was reported from hypersaline waters (55 pps) in the Black Sea (Russell, 2013). Sensitivity assessment. Arenicola marina was able to survive and adapt to short-term exposure to 47 psu (Zebe & Schiedek, 1996) but no evidence of the effect of long-term increases in salinity of hypersaline effluents was found. The synaptid holothurians may not as species vary in their resistance to changes in salinity but no direct evidence was found. Therefore, no assessment was made. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Salinity decrease (local) [Show more]Salinity decrease (local)Benchmark. A decrease in one MNCR salinity category above the usual range of the biotope or habitat. Further detail EvidenceThis biotope is recorded from full salinity (Connor et al., 2004). However, this biotope was reported to occur at 24-35 psu and 18-35 psu in Scottish lagoons (Thorpe et al. 1998; Thorpe, 1998) Arenicola marina was recorded in biotope from ‘full’ to reduced salinity (Connor et al., 2004). Once the salinity of the overlying water drops below about 55% seawater (about 18psu) Arenicola marina stops irrigation and compresses itself at the bottom of its burrow. It raises its tails to the head of the burrow to 'test' the water at intervals, about once an hour. Once normal salinities return they resume usual activity (Shumway & Davenport, 1977; Rankin & Davenport,1981; Zebe & Schiedek, 1996). This behaviour, together with their burrow habitat, enabled the lugworm to maintain its coelomic fluid and tissue constituents at a constant level, whereas individuals exposed to fluctuating salinities outside their burrow did not (Shumway & Davenport, 1977). Environmental fluctuations in salinity are only likely to affect the surface of the sediment, and not deeper organisms since the interstitial or burrow water is little affected. However, lugworms may be affected by low salinities at low tide after heavy rains. Arenicola marina was able to osmoregulate intracellular and extracellular volume within 72 - 114 hrs by increased urine production and increased amino acid concentration in response to hypo-osmotic shock (low salinity) (see Zebe & Schiedek, 1996). Hayward (1994) suggested that Arenicola marina is unable to tolerate salinities below 24 psu and is excluded from areas influenced by freshwater runoff or input (e.g. the head end of estuaries) where it is replaced by Hediste diversicolor . However, Barnes (1994) reported that Arenicola marina occurred at salinities down to 18 psu in Britain, but survived as low as 8 psu in the Baltic, whereas Shumway & Davenport (1977) reported that this species cannot survive less than 10 psu in the Baltic. However, Arenicola marina was also found in the western Baltic where salinities were as low as 10 ppt, and Baltic specimens survived at 6 ppt (Zebe & Schiedek, 1996). Therefore, regional populations can adapt to brackish conditions. Echinoderms are generally regarded as stenohaline and most species are exclusively marine (Binyon, 1966; Pawson, 1966; Stickle & Diehl, 1987; Lawrence, 1996; Russell, 2013). Leptosynapta inhaerens occurred at 18.46 psu in the Black Sea (Russell, 2013). Leptosynapta sp. may derive some protection from a short-term reduction in salinity due to their burrowing habitat, however, Labidoplax media may be more vulnerable. Sensitivity assessment. The evidence suggests that a reduction in salinity from ‘full’ to ‘reduced’ for a year is unlikely to adversely affect the resident Arenicola population. Mobile members of the community typically occur in the intertidal and are also probably unaffected, although the synaptid holothurians may migrate out of the biotope. Therefore, a resistance of High is suggested. Hence, resilience is High and the biotope is assessed as Not sensitive at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Water flow (tidal current) changes (local) [Show more]Water flow (tidal current) changes (local)Benchmark. A change in peak mean spring bed flow velocity of between 0.1 m/s to 0.2 m/s for more than one year. Further detail EvidenceThe biotope is found in weak (<0.5 m/s) to very weak (negligible) flow in very sheltered, shallow, soft muds in sheltered basins of sea lochs and lagoons, and is typified by very conspicuous mounds and casts (Connor et al., 2004). In 36-65 day mesocosm studies of the effects of Arenicola marina bioturbation, Wendelboe et al. (2013) found that the surface of the sediment was dominated faecal mounds and feeding pits at a flow rate of 0.11 m/s but was more eroded and the surface was more even at 0.25 m/s. At the low flow (0.11 m/s) there was no change in the sediment. But at 0.25 m/s, there was a substantial reduction in the silt and clay fractions of the sediment (a 36% reduction) and in the organic content of the sediment (a 42% reduction). At 0.25 m/s the material ejected into faecal casts was eroded (once the mucilaginous coating had eroded) and the water surface became turbid, resulting in loss of both silt/clay fractions and organic matter. Wendelboe et al. (2013) concluded that at ‘high’ flow (0.25 m/s) bioturbation by Arenicola (or other fauna) could lead to a gradual change in the sediment in the bioturbated sediment layer (i.e. the upper few centimetres). However, their experiment was a closed system, whereas the biotope is likely to receive regular input of organic matter. Arenicola marina is generally absent from sediments with a mean particle size of <80µm and abundance declines in sediments >200µm (fine sand) because they cannot ingest large particles. Its absence from more fluid muddy sediments is probably because they do not produce large amounts of mucus with which to stabilise their burrows. Populations are greatest in sands of mean particle size of 100 µm. Between 100 and 200 µm the biomass of Arenicola marina increases with increasing organic content (Longbottom, 1970; Hayward, 1994). However, it is recorded from a variety of sediments from fine muds to muddy sands and sandy muds, clean sand and mixed sediments (Connor et al., 1997b). Sensitivity assessment. The biotope occurs in weak to very weak flow so that any further reduction is not relevant. An increase in water flow could modify the sediment. A significant increase may result in a change in the sediment from fine muds to sand muds and the fine particulates are removed. The experimental evidence suggests that a change in the flow of 0.11 m/s to 0.25 m/s was enough to alter the sediment and the appearance of the biotope within 65 days. Therefore, a change in the flow of 0.1-0.2 m/s may alter the sediment and the appearance of the biotope. The Arenicola population would persist although the biotope may come to resemble a muddy sand biotope (e.g. IMuSa.AreISa) and be reclassified. Therefore, a resistance of None is suggested. Resilience is probably High as, once the low energy conditions return, it may only take a couple of years for the mud to deposit in these otherwise sheltered and isolated habitats. Hence, sensitivity is assessed as Medium. | NoneHelp | HighHelp | MediumHelp |

Emergence regime changes [Show more]Emergence regime changesBenchmark. 1) A change in the time covered or not covered by the sea for a period of ≥1 year or 2) an increase in relative sea level or decrease in high water level for ≥1 year. Further detail EvidenceChanges in emergence is only relevant to intertidal and sublittoral fringe biotopes. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Wave exposure changes (local) [Show more]Wave exposure changes (local)Benchmark. A change in near shore significant wave height of >3% but <5% for more than one year. Further detail EvidenceThe biotope is recorded in extremely or very wave sheltered conditions and weak or very weak flow. The low energy habitat is probably crucial for the accumulation of the fine muds that typify the biotope. A further decrease in wave action is not relevant. However, an increase in wave action (e.g. due to an increase in average storminess or a loss of the barrier that creates the isolated situations in which theses habitats form) would probably result in modification of the sediment and a change to more sandy conditions, depending on the magnitude of the increase. If muddy or sandy sediments remain, the Arenicola population would probably persist, but the biotope would be reclassified and lost. Nevertheless, a 3-5% increase in significant wave height (the benchmark) is unlikely to be significant and the biotope is assessed as Not sensitive (resistance and resilience are High) at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Chemical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Transition elements & organo-metal contamination [Show more]Transition elements & organo-metal contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceSediment may act as a sink for heavy metals contamination so that deposit feeding species may be particularly vulnerable to heavy metal contamination through ingestion of particulates. At high concentrations of Cu, Cd or Zn the blow lug left the sediment (Bat & Raffaelli, 1998). The following toxicities have been reported in Arenicola marina:

However, Bryan (1984) suggested that polychaetes are fairly resistant to heavy metals, based on the species studied. Short-term toxicity in polychaetes was highest to Hg, Cu and Ag, declined with Al, Cr, Zn and Pb whereas Cd, Ni, Co and Se the least toxic. Little is known about the effects of heavy metals on echinoderms. Bryan (1984) reported that early work had shown that echinoderm larvae were intolerant of heavy metals, e.g. the intolerance of larvae of Paracentrotus lividus to copper (Cu) had been used to develop a water quality assessment. Kinne (1984) reported developmental disturbances in Echinus esculentus exposed to waters containing 25 µg / l of copper (Cu). Sea urchins, especially the eggs and larvae, are used for toxicity testing and environmental monitoring (reviewed by Dinnel et al. 1988). Crompton (1997) reported that mortalities occurred in echinoderms after 4-14day exposure to above 10-100 µg/l Cu, 1-10 mg/l Zn and 10-100 mg/l Cr but that mortality occurred in echinoderm larvae above10-100 µg/ l Ni. Nevertheless, this pressure is Not assessed but evidence is presented where available. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Hydrocarbon & PAH contamination [Show more]Hydrocarbon & PAH contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceSheltered embayments and lagoons, where this biotope is found, are particularly vulnerable to oil pollution, which may settle onto the sediment and persist for years (Cole et al., 1999). Subsequent digestion or degradation of the oil by microbes may result in nutrient enrichment and eutrophication (see nutrients below). Although protected from direct smothering by oil by its depth, the biotope is relatively shallow and would be exposed to the water soluble fraction of oil, water soluble PAHs, and oil adsorbed onto particulates. Suchanek (1993) reviewed the effects of oil spills on marine invertebrates and concluded that, in general, on soft sediment habitats, infaunal polychaetes, bivalves and amphipods were particularly affected. Crude oil and oil: dispersant mixtures were shown to cause mortalities in Arenicola marina (see review). Prouse & Gordon (1976) found that blow lug was driven out of the sediment by waterborne fuel oil concentrations of >1 mg/l or sediment concentration of >100 µg/g. Crude oil and refined oils were shown to have little effect on fertilization in sea urchin eggs but in the presence of dispersants, fertilization was poor and embryonic development was impaired (Johnston, 1984). Sea urchin eggs showed developmental abnormalities when exposed to 10-30mg/l of hydrocarbons and crude oil : Corexit dispersant mixtures have been shown to cause functional loss of tube feet and spines in sea urchins (Suchanek, 1993). Although no direct information on synaptid holothurians was found, it seems likely that adults and especially larvae are intolerant of hydrocarbon contamination. Nevertheless, this pressure is Not assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Synthetic compound contamination [Show more]Synthetic compound contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed but evidence is presented where available. The xenobiotic ivermectin was used to control parasitic infestations in livestock including sea lice in fish farms, degrades slowly in marine sediments (half-life >100 days). Ivermectin was found to produce a 10 day LC50 of 18µg ivermectin /kg of wet sediment in Arenicola marina. Sub-lethal effects were apparent between 5 - 105 µg/kg. Cole et al. (1999) suggested that this indicated a high intolerance. Arenicola marina has shown negative responses to chemical contaminants, including damaged gills following exposure to detergents (Conti, 1987), and inhibited the action of esterases following suspected exposure to point source pesticide pollution in sediments from the Ribble estuary, UK (Hannam et al., 2008). Little information on the toxicity of synthetic chemicals to synaptid holothurians was found. Newton & McKenzie (1995) suggested that echinoderms tend to be very intolerant of various types of marine pollution but gave no detailed information. Cole et al. (1999) reported that echinoderm larvae displayed adverse effects when exposed to 0.15mg/l of the pesticide Dichlorobenzene (DCB). Smith (1968) demonstrated that 0.5 -1ppm of the detergent BP1002 resulted in developmental abnormalities in echinopluteus larvae of Echinus esculentus. Therefore, the larvae of synaptid holothurians may also be intolerant of synthetic chemicals. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Radionuclide contamination [Show more]Radionuclide contaminationBenchmark. An increase in 10µGy/h above background levels. Further detail EvidenceReports on littoral sediment benthic communities at Sandside Bay, adjacent to Dounray nuclear facility, Scotland, (where radioactive particles have been detected and removed) reported Arenicola marina were abundant (SEPA, 2008). Kennedy et al. (1988) reported levels of 137Cs in Arenicola spp. of 220-440 Bq/kg from the Solway Firth. However, no information on the effects of radionuclide contamination was found. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Introduction of other substances [Show more]Introduction of other substancesBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

De-oxygenation [Show more]De-oxygenationBenchmark. Exposure to dissolved oxygen concentration of less than or equal to 2 mg/l for one week (a change from WFD poor status to bad status). Further detail EvidenceArenicola marina is subject to reduced oxygen concentrations regularly at low tide and is capable of anaerobic respiration. The transition from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism takes several hours and is complete within 6-8 hrs, although this is likely to be the longest period of exposure at low tide. Fully aerobic metabolism is restored within 60 min once oxygen returns (Zeber & Schiedek, 1996). This species was able to survive anoxia for 90 hrs in the presence of 10 mmol/l sulphide in laboratory tests (Zeber & Schiedek, 1996). Hydrogen sulphide (H2S) produced by chemoautotrophs within the surrounding anoxic sediment and may, therefore, be present in Arenicola marina burrows. Although the population density of Arenicola marina decreases with increasing H2S, Arenicola marina is able to detoxify H2S in the presence of oxygen and maintain a low internal concentration of H2S. At high concentrations of H2S in the lab (0.5, 0.76 and 1.26 mmol/l) the lugworm resorts to anaerobic metabolism (Zeber & Schiedek, 1996). At 16°C Arenicola marina survived 72 hrs of anoxia but only 36 hrs at 20°C. Tolerance of anoxia was also seasonal, and in winter anoxia tolerance was reduced at temperatures above 7°C. Juveniles have a lower tolerance of anoxia but are capable of anaerobic metabolism (Zebe & Schiedek, 1996). However, Arenicola marina has been found to be unaffected by short periods of anoxia and to survive for 9 days without oxygen (Borden, 1931 and Hecht, 1932 cited in Dales, 1958; Hayward, 1994). Diaz & Rosenberg (1995) listed Arenicola marina as a species resistant of severe hypoxia. Nilsson & Rosenberg (1994) exposed sediment cores, containing Labidoplax buskii and other benthic species to moderate (1mg O2/l) and severe (0.5mg O2/l) hypoxia for 20 days. Labidoplax buskii was seen to leave the sediment when the oxygen concentration was reduced to 1.6 mg O2/l (16% saturation) and were dead by the end of the experiment in both moderate and severe hypoxia experiments. However, little other information on tolerance of hypoxia in synaptid holothurians was found. Sensitivity assessment. The fine muddy sediments found in this biotope are organic rich and the benthic macrofauna is probably adapted to a degree of hypoxia. Burrowing species such as Arenicola marina and Leptosynapta sp. burrow into anoxic sediment and may be tolerant of hypoxia. Using Labidoplax buskii and Arenicola marina as examples, the characterizing species would probably survive exposure to 2mg O2/l for one week (the benchmark) although they may incur a metabolic cost or reduced feeding during exposure. Therefore, resistance is assessed as High, resilience as High (by default) and the biotope is probably Not sensitive at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Nutrient enrichment [Show more]Nutrient enrichmentBenchmark. Compliance with WFD criteria for good status. Further detail EvidenceThe abundance and biomass of Arenicola marina increase with increased organic content in their favoured sediment (Longbottom, 1970; Hayward, 1994). Therefore, moderate nutrient enrichment may be beneficial. Indirect effects may include algal blooms and the growth of algal mats (e.g. of Ulva sp.) on the surface of the intertidal flats. Algal mats smother the sediment, and create anoxic conditions in the sediment underneath, changes in the microphytobenthos, and with increasing enrichment, a reduction in species richness, the sediment becoming dominated by pollution tolerant polychaetes, e.g. Manayunkia aestuarina. In extreme cases, the sediment may become anoxic and defaunated (Elliot et al., 1998). Algal blooms have been implicated in mass mortalities of lugworms, e.g. in South Wales where up to 99% mortality was reported (Boalch, 1979; Olive & Cadman, 1990; Holt et al. 1995). Feeding lugworms were present and exploitable by bait diggers within 1 month, suggesting rapid recovery, probably by migration from surrounding areas or juvenile nurseries. Nevertheless, this biotope is considered to be Not sensitive at the pressure benchmark that assumes compliance with good status as defined by the WFD. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not sensitiveHelp |

Organic enrichment [Show more]Organic enrichmentBenchmark. A deposit of 100 gC/m2/yr. Further detail EvidenceThe abundance and biomass of Arenicola marina increase with increased organic content in their favoured sediment (Longbottom, 1970; Hayward, 1994). Moderate enrichment increases food supplies, enhancing productivity and abundance. Gray et al. (2002) concluded that organic deposits between 50 to 300 gC m–2 yr–1, are efficiently processed by benthic species. Substantial increases > 500 g C m-2 yr-1 would likely to have negative effects, limiting the distribution of organisms and degrade the habitat, leading to eutrophication, algal blooms, and changes in community structure to a community dominated by opportunist species (e.g. capitellids) with increased abundance but reduced species richness, and eventually to abiotic anoxic sediments (Pearson & Rosenberg, 1978; Gray, 1981; Snelgrove et al.,1995; Cromey et al., 1998). Borja et al. (2000) and Gittenberger & loon (2011) placed Arenicola marina into the AMBI pollution group III, defined as ‘Species tolerant to excess organic matter enrichment. These species may occur under normal conditions, but their populations are stimulated by organic enrichment (slight unbalance situations)’. Sensitivity assessment. The biotope is probably rich in organic matter as it occurs in sheltered, isolated areas. Therefore, a resistance of High is suggested at the benchmark level. Hence, resilience is High and the biotope is assessed as Not sensitive at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Physical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Physical loss (to land or freshwater habitat) [Show more]Physical loss (to land or freshwater habitat)Benchmark. A permanent loss of existing saline habitat within the site. Further detail EvidenceAll marine habitats and benthic species are considered to have a resistance of ‘None’ to this pressure and to be unable to recover from a permanent loss of habitat (resilience is ‘Very Low’). Sensitivity within the direct spatial footprint of this pressure is, therefore, ‘High’. Although no specific evidence is described confidence in this assessment is ‘High’, due to the incontrovertible nature of this pressure. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical change (to another seabed type) [Show more]Physical change (to another seabed type)Benchmark. Permanent change from sedimentary or soft rock substrata to hard rock or artificial substrata or vice-versa. Further detail EvidenceThis biotope is only found in sediment and the burrowing organisms, Arenicola marina and synaptid holothurians would not be able to survive if the substratum type was changed to either a soft rock or hard artificial type, and the biotope would be lost. Sensitivity assessment. The resistance to this change is ‘None’, and the resilience is assessed as ‘Very low’ as the change at the pressure benchmark is permanent. The biotope is assessed to have a ‘High’ sensitivity to this pressure at the benchmark. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical change (to another sediment type) [Show more]Physical change (to another sediment type)Benchmark. Permanent change in one Folk class (based on UK SeaMap simplified classification). Further detail EvidenceThis biotope (IFiMu.Are) is only found in shallow, sheltered conditions and is defined by the presence of fine mud. A change in sediment type by one Folk class (using the Long 2006 simplification) would change the sediment to muddy sand or sand. Although the Arenicola population would persist, the biotope would be lost and reclassified, probably as IMuSa.ArelSa. Therefore, a resistance of None is recorded, resilience is Very low (the pressure is a permanent change) and sensitivity is assessed as High. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Habitat structure changes - removal of substratum (extraction) [Show more]Habitat structure changes - removal of substratum (extraction)Benchmark. The extraction of substratum to 30 cm (where substratum includes sediments and soft rock but excludes hard bedrock). Further detail EvidenceExtraction of sediment to a depth of 30 cm would remove the community within the affected area. Therefore, a resistance of None is suggested. Resilience is probably Medium, due to the isolated nature of the sea lochs and lagoons in which this biotope is found, and sensitivity is assessed as Medium. | NoneHelp | MediumHelp | MediumHelp |

Abrasion / disturbance of the surface of the substratum or seabed [Show more]Abrasion / disturbance of the surface of the substratum or seabedBenchmark. Damage to surface features (e.g. species and physical structures within the habitat). Further detail EvidenceArenicola marina lives in sediment to a depth of 20-40 cm and is, therefore, protected from most sources of abrasion and physical disturbance caused by surface action. However, it is likely to be damaged by any activity (e.g. anchors, dredging) that penetrates the sediment (see below). Leptosynapta sp. also lives in burrows in the sediment. Labidoplax media lives in the top few cm of the sediment are, therefore, more vulnerable to abrasion but also likely to burrow to safety. There are few studies on the effects of trampling on sedimentary habitats. Most studies suggest that the effects of trampling across sedimentary habitats depend on the relative proportion of mud to sand (sediment porosity), the dominant infauna (nematodes and polychaetes vs. bivalves) and the presence of burrows (Tyler-Walters & Arnold, 2008). Recovery from impact is relatively fast as shown by Chandrasekara & Frid (1996), where no difference was reported between samples in winter following summer trampling. Wynberg & Branch (1997) suggest that trampling effects are most severe in sediments dominated by animals with stable burrows, as these collapse and the sediment becomes compacted. Rossi et al. (2007) examined trampling across intertidal mudflats but were not able to show a significant difference in Arenicola abundance between trampled and control sites due to the natural variation in abundance between study sites. Rees (1978 cited in Hiscock et al., 2002) assessed pipe laying activity in Lafan Sands, Conwy Bay, Wales. The pipe was laid in a trench dug by excavators. The spoil from the trenching was then used to bury the pipe. The trenching severely disturbed a narrow zone, but a zone some 50 m wide on each side of the pipeline was also disturbed by the passage of vehicles. The tracked vehicles damaged and exposed shallow-burrowing species such as the bivalves Cerastoderma edule and Macoma balthica, which were then preyed upon by birds. Deeper-dwelling species were apparently less affected; casts of the lugworm Arenicola marina and feeding marks made by the bivalve Scrobicularia plana were both observed in the vehicle tracks. During the construction period, the disturbed zone was continually re-populated by mobile organisms, such as the gastropod Hydrobia ulvae. Post-disturbance recolonization was rapid. Several species, including the polychaetes Arenicola marina, Eteone longa and Scoloplos armiger recruited preferentially to the disturbed area. However, the numbers of the relatively long-lived Scrobicularia plana were markedly depressed, without signs of obvious recruitment several years after the pipeline operations had been completed. Sensitivity assessment. Although this biotope is found in the subtidal it is shallow (0-10 m) so that it is theoretically possible for vehicles or pedestrians to traverse the biotope. Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that Arenicola is little affected by abrasion in the form of trampling or vehicle compaction. Therefore, a resistance of High is suggested so that resilience is also High (by default) and the biotope is probably Not sensitive to abrasion due to trampling or vehicular access. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Penetration or disturbance of the substratum subsurface [Show more]Penetration or disturbance of the substratum subsurfaceBenchmark. Damage to sub-surface features (e.g. species and physical structures within the habitat). Further detail EvidenceMendonça et al. (2008) studied populations of the polychaete Arenicola marina at Culbin Sands lagoon, Moray Firth, in NE Scotland. An unprecedented and unexpected cockle harvesting event took place,1.5 years after the start of the sampling programme, which dramatically disturbed the sediment as it was conducted using tractors with mechanical rakes in some areas, and by boats using a suction dredge in other areas. Therefore, there was an opportunity to compare annual biomass fluctuations “before” and “after” the disturbance. Arenicola marina was observed to return to normal activities just a few hours after the disturbance of the sediment during the harvesting event. Rees (1978 cited in Hiscock et al., 2002) assessed pipe laying activity in Lafan Sands, Conwy Bay, Wales. The pipe was laid in a trench dug by excavators. The spoil from the trenching was then used to bury the pipe. The trenching severely disturbed a narrow zone, but a zone some 50 m wide on each side of the pipeline was also disturbed by the passage of vehicles. The tracked vehicles damaged and exposed shallow-burrowing species such as the bivalves Cerastoderma edule and Macoma balthica, which were then preyed upon by birds. Deeper-dwelling species were apparently less affected; casts of the lugworm Arenicola marina and feeding-marks made by the bivalve Scrobicularia plana were both observed in the vehicle tracks. During the construction period, the disturbed zone was continually re-populated by mobile organisms, such as the gastropod Hydrobia ulvae. Post-disturbance recolonization was rapid. Several species, including the polychaetes Arenicola marina, Eteone longa and Scoloplos armiger recruited preferentially to the disturbed area. However, the numbers of the relatively long-lived Scrobicularia plana were markedly depressed, without signs of obvious recruitment several years after the pipeline operations had been completed. McLusky et al. (1983) examined the effects of bait digging on blow lug populations in the Forth estuary. Dug and infilled areas and unfilled basins left after digging re-populated within 1 month, whereas mounds of dug sediment took showed a reduced population. The basins accumulated fine sediment and organic matter and showed increased population levels for about 2-3 months after digging. Fowler (1999) reviewed the effects of bait digging on intertidal fauna, including Arenicola marina. Diggers were reported to remove 50 or 70% of the blow lug population. Heavy commercial exploitation in Budle Bay in winter 1984 removed 4 million worms in 6 weeks, reducing the population from 40 to <1 per m². Recovery occurred within a few months by recolonization from surrounding sediment (Fowler, 1999). However, Cryer et al. (1987) reported no recovery for 6 months over summer after mortalities due to bait digging. Mechanical lugworm dredgers were used in the Dutch Wadden Sea where they removed 17-20 million lugworms/year. However, when combined with hand digging the harvest represented only 0.75% of the estimated population in the area. A near doubling of the lugworm mortality in dredged areas was reported, resulting in a gradual substantial decline in the local population over a 4 year period. The effects of mechanical lugworm dredging are more severe and can result in the complete removal of Arenicola marina (Beukema, 1995; Fowler, 1999). Beukema (1995) noted that the lugworm stock recovered slowly reached its original level in at least three years. Sensitivity assessment. Penetrative gear would probably damage or remove a proportion of the population of Arenicola but given its potential density, the effects may be minor. Similarly, recreational bait digging may have a limited effect. However, if commercial bait digging occurred in the shallow sublittoral, then a significant proportion of the population may be removed. Hence, a resistance of Low is suggested. Resilience is probably Medium, due to the isolated nature of the sea lochs and lagoons in which this biotope if found, and sensitivity is assessed as Medium. | LowHelp | MediumHelp | MediumHelp |

Changes in suspended solids (water clarity) [Show more]Changes in suspended solids (water clarity)Benchmark. A change in one rank on the WFD (Water Framework Directive) scale e.g. from clear to intermediate for one year. Further detail EvidenceThis biotope occurs in fine silts and muds that accumulate in low energy environments (wave sheltered and weak flow) in shallow isolated water bodies. Deposit feeders are unlikely to be perturbed by increased concentrations of suspended sediment since they live in sediment and are probably adapted to re-suspension of sediment by wave action, during storms or runoff. In 36-65 day mesocosm studies of the effects of Arenicola marina bioturbation, Wendelboe et al. (2013) found that the surface of the sediment was dominated by faecal mounds and feeding pits at a flow rate of 0.11 m/s, but was more eroded and the surface was more even at 0.25 m/s. At the low flow (0.11 m/s) there was no change in the sediment. However, at 0.25 m/s, there was a substantial reduction in the silt and clay fractions of the sediment (a 36% reduction) and in the organic content of the sediment (a 42% reduction). At 0.25 m/s the material ejected into faecal casts was eroded (once the mucilaginous coating had eroded) and the water surface became turbid, resulting in loss of both silt/clay fractions and organic matter. Sensitivity assessment. The evidence from Wendelboe et al. (2013) suggests that an increase in water movement due to storms, or runoff is likely to disturb the sediment surface regularly, especially in winter months, so that the biotope is probably not affected by changes in suspended sediment. In addition, Arenicola marina occurs at high abundances in mudflats and sandflats in estuaries where suspended sediment levels may reach grammes per litre. Therefore, a resistance of High is suggested so that resilience is High (by default) and the biotope is assessed as Not sensitive at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Smothering and siltation rate changes (light) [Show more]Smothering and siltation rate changes (light)Benchmark. ‘Light’ deposition of up to 5 cm of fine material added to the seabed in a single discrete event. Further detail EvidenceArenicola marina is a sub-surface deposit feeder that derives the sediment it ingests from the surface. It rapidly reworks and mixes sediment. It grows to 12-20 cm in length and lives in burrows to a depth of 20-40 cm. It is unlikely to be perturbed by smothering by 5 cm of sediment. Juveniles may be more susceptible but both adults and juveniles are capable of leaving the sediment and swimming (on the tide) up or down the shore (see Reise et al., 2001). If present, Leptosynapta bergensis has a similar lifestyle and is also unlikely to be intolerant of smothering at the level of the benchmark. Labidoplax media lives in the top few cm of sediment and will incur an energetic cost, due to its relatively small size. In addition, Gittenberger & Loon (2011) placed Arenicola marina into their AMBI Sedimentation Group III, defined as ‘species insensitive to higher amounts of sedimentation, but don’t easily recover from strong fluctuations in sedimentation’. Sensitivity assessment. This biotope occurs in a depositional environment, where sedimentation is likely, to be high due to the low energy of the habitat. Therefore, resistance to a deposit of 5 cm of fine sediment is assessed as High. Hence, resilience is High (by default) and the biotope is probably Not sensitive at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Smothering and siltation rate changes (heavy) [Show more]Smothering and siltation rate changes (heavy)Benchmark. ‘Heavy’ deposition of up to 30 cm of fine material added to the seabed in a single discrete event. Further detail EvidenceArenicola marina is a sub-surface deposit feeder that derives the sediment it ingests from the surface. It rapidly reworks and mixes sediment. It grows to 12-20 cm in length and lives in burrows to a depth of 20-40 cm. Adults may be able to resist smothering by 30 cm of sediment but juveniles may be more susceptible. Both adults and juveniles are capable of leaving the sediment and swimming (on the tide) up or down the shore (see Reise et al., 2001). If present, Leptosynapta bergensis has a similar lifestyle and is also unlikely to be intolerant of smothering at the level of the benchmark. Labidoplax media lives in the top few cm of sediment and will incur an energetic cost, due to its relatively small size. In addition, Gittenberger & Loon (2011) placed Arenicola marina into their AMBI sedimentation Group III, defined as ‘species insensitive to higher amounts of sedimentation, but don’t easily recover from strong fluctuations in sedimentation’. Sensitivity assessment. This biotope occurs in a depositional environment, where sedimentation is likely, to be high due to the low energy of the habitat. However, the deposit of 30 cm in a single event is probably greater than the normal range of sedimentation and, in theses sheltered habitats, likely to remain. Therefore, a proportion of the adults and a greater proportion of the juveniles may not be able to realign themselves with the surface of the sediment and resistance is assessed as Medium but at ‘Low’ confidence due to the lack of direct evidence. Hence, resilience is probably High and sensitivity is assessed as Low at the benchmark level. | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Litter [Show more]LitterBenchmark. The introduction of man-made objects able to cause physical harm (surface, water column, seafloor or strandline). Further detail EvidencePlastic debris breaks up to form microplastics. Microplastics have been shown to occur in marine sediments and to be ingested by deposit feeders such as Arenicola marina and holothurians, as well as by suspension feeders, e.g. Mytilus edulis (Wright et al., 2013b; Browne et al., 2015). Wright et al. (2013) showed that the presence of microplastics (5% UPVC) in a lab study significantly reduced feeding activity when compared to concentrations of 1% UPVC and controls. As a result, Arenicola marina showed significantly decreased energy reserves (by 50%), took longer to digest food, and as a result decreased bioturbation levels, which would be likely to impact colonization of sediment by other species, reducing diversity in the biotopes the species occurs within. Wright et al. (2013) suggested that in the intertidal regions of the Wadden Sea, where Arenicola marina is an important ecosystem engineer, Arenicola marina could ingest 33m3 of microplastics a year. In a similar experiment, Browne et al. (2013) exposed Arenicola marina to sediments with 5% PVC particles or sand presorbed with pollutants nonylophenol and phenanthrene for 10 days. PVC is dense and sinks to the sediment. The experiment used Both microplastics and sand transferred the pollutants into the tissues of the lugworm by absorption through the gut. The worms accumulated over 250% more of these pollutants from sand than from the PVC particulates. The lugworms were also exposed to PVC particulates presorbed with plastic additive, the flame retardant PBDE-47 and antimicrobial Triclosan. The worms accumulated up to 3,500% of the concentration of theses contaminants when compared when to the experimental sediment. Clean sand and PVC with contaminants reduced feeding but PVC with Triclosan reduced feeding by over 65%. In the PVC with Triclosan treatments 55% of the lugworms died. Browne et al, 2013 concluded that the contaminants tested reduced feeding, immunity, response to oxidative stress, and survival (in the case of Triclosan). Sensitivity assessment. Impacts from the pressure ‘litter’ would depend upon the exact form of litter or man-made object being introduced. Browne et al. (2015) suggested that if effects in the laboratory occurred in nature, they could lead to significant changes in sedimentary communities, as Arenicola marina is an important bioturbators and ecosystem engineer in sedimentary habitats. Nevetheless, while significant impacts have been shown in laboratory studies, impacts at biotope scales are still unknown and this pressure is Not assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Electromagnetic changes [Show more]Electromagnetic changesBenchmark. A local electric field of 1 V/m or a local magnetic field of 10 µT. Further detail EvidenceNo evidence was found | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Underwater noise changes [Show more]Underwater noise changesBenchmark. MSFD indicator levels (SEL or peak SPL) exceeded for 20% of days in a calendar year. Further detail EvidenceSpecies within the biotope can probably detect vibrations caused by noise and in response may retreat into the sediment for protection. However, at the benchmark level, the community is unlikely to be respond to noise and therefore is Not sensitive. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Introduction of light or shading [Show more]Introduction of light or shadingBenchmark. A change in incident light via anthropogenic means. Further detail EvidenceAll characterizing species live in the sediment and do not rely on light levels directly to feed or so limited direct impact is expected. As this biotope is not characterized by the presence of primary producers it is not considered that shading would alter the character of the habitat directly. Beneath shading structures, there may be changes in microphytobenthos abundance. This biotope may support microphytobenthos on the sediment surface and within the sediment. Mucilaginous secretions produced by these algae may stabilise fine substrata (Tait & Dipper, 1998). Shading will prevent photosynthesis leading to death or migration of sediment microalgae altering sediment cohesion and food supply to deposit feeders like Arenicola and synaptid holothurians, although they fed on a range of organic matter within the sediment. Sensitivity assessment. Therefore, biotope resistance is assessed as ‘High’ and resilience is assessed as ‘High’ (by default) and the biotope is considered to be ‘Not sensitive’. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Barrier to species movement [Show more]Barrier to species movementBenchmark. A permanent or temporary barrier to species movement over ≥50% of water body width or a 10% change in tidal excursion. Further detail EvidenceNot relevant - this pressure is considered applicable to mobile species, e.g. fish and marine mammals rather than seabed habitats. Physical and hydrographic barriers may limit the dispersal of seed. But seed dispersal is not considered under the pressure definition and benchmark. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not sensitiveHelp |

Death or injury by collision [Show more]Death or injury by collisionBenchmark. Injury or mortality from collisions of biota with both static or moving structures due to 0.1% of tidal volume on an average tide, passing through an artificial structure. Further detail EvidenceNot relevant to seabed habitats. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Visual disturbance [Show more]Visual disturbanceBenchmark. The daily duration of transient visual cues exceeds 10% of the period of site occupancy by the feature. Further detail EvidenceNot relevant. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Biological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Genetic modification & translocation of indigenous species [Show more]Genetic modification & translocation of indigenous speciesBenchmark. Translocation of indigenous species or the introduction of genetically modified or genetically different populations of indigenous species that may result in changes in the genetic structure of local populations, hybridization, or change in community structure. Further detail EvidenceImportant characterizing species within this biotope are not genetically modified or translocated. Therefore, This pressure is considered ‘Not relevant’ to this biotope group. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Introduction of microbial pathogens [Show more]Introduction of microbial pathogensBenchmark. The introduction of relevant microbial pathogens or metazoan disease vectors to an area where they are currently not present (e.g. Martelia refringens and Bonamia, Avian influenza virus, viral Haemorrhagic Septicaemia virus). Further detail EvidenceAshworth (1904) recorded the presence of distomid cercariae and Coccidia in Arenicola marina from the Lancashire coast. However, no information concerning infestation or disease related mortalities was found. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Removal of target species [Show more]Removal of target speciesBenchmark. Removal of species targeted by fishery, shellfishery or harvesting at a commercial or recreational scale. Further detail EvidenceMcLusky et al. (1983) examined the effects of bait digging on blow lug populations in the Forth estuary. Dug and infilled areas and unfilled basins left after digging re-populated within 1 month, whereas mounds of dug sediment took showed a reduced population. The basins accumulated fine sediment and organic matter and showed increased population levels for about 2-3 months after digging. Fowler (1999) reviewed the effects of bait digging on intertidal fauna, including Arenicola marina. Diggers were reported to remove 50 or 70% of the blow lug population. Heavy commercial exploitation in Budle Bay in winter 1984 removed 4 million worms in 6 weeks, reducing the population from 40 to <1 per m². Recovery occurred within a few months by recolonization from surrounding sediment (Fowler, 1999). However, Cryer et al. (1987) reported no recovery for 6 months over summer after mortalities due to bait digging. Mechanical lugworm dredgers were used in the Dutch Wadden Sea where they removed 17-20 million lugworms/year. However, when combined with hand digging the harvest represented only 0.75% of the estimated population in the area. A near doubling of the lugworm mortality in dredged areas was reported, resulting in a gradual substantial decline in the local population over a 4 year period. The effects of mechanical lugworm dredging are more severe and can result in the complete removal of Arenicola marina (Beukema, 1995; Fowler, 1999). Beukema (1995) noted that the lugworm stock recovered slowly reached its original level in at least three years. Sensitivity assessment. Recreational bait digging may remove a proportion of the population of Arenicola but given its potential density, the effects may be minor. However, if commercial bait digging occurred in the shallow sublittoral, then a significant proportion of the population may be removed. The physical effects of removal are addressed under penetration above. However, Arenicola marina is a bioturbator and ecosystem engineer and its removal would probably have a significant effect on the nature of the sediment and the other species that could inhabit the sediment. Hence, a resistance of Low is suggested. Resilience is probably Medium, due to the isolated nature of the sea lochs and lagoons in which this biotope if found, and sensitivity is assessed as Medium. | LowHelp | MediumHelp | MediumHelp |

Removal of non-target species [Show more]Removal of non-target speciesBenchmark. Removal of features or incidental non-targeted catch (by-catch) through targeted fishery, shellfishery or harvesting at a commercial or recreational scale. Further detail EvidenceArenicola marina is a bioturbator and ecosystem engineer and its incidental removal would probably have a significant effect on the nature of the sediment and the other species that could inhabit the sediment. Hence, a resistance of Low is suggested. Resilience is probably Medium, due to the isolated nature of the sea lochs and lagoons in which this biotope if found, and sensitivity is assessed as Medium. | LowHelp | MediumHelp | MediumHelp |

Introduction or spread of invasive non-indigenous species (INIS) Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |