Sponges, shade-tolerant red seaweeds and Dendrodoa grossularia on wave-surged overhanging lower eulittoral bedrock and caves

| Researched by | John Readman, Dr Harvey Tyler-Walters & Amy Watson | Refereed by | This information is not refereed |

|---|

Summary

UK and Ireland classification

Description

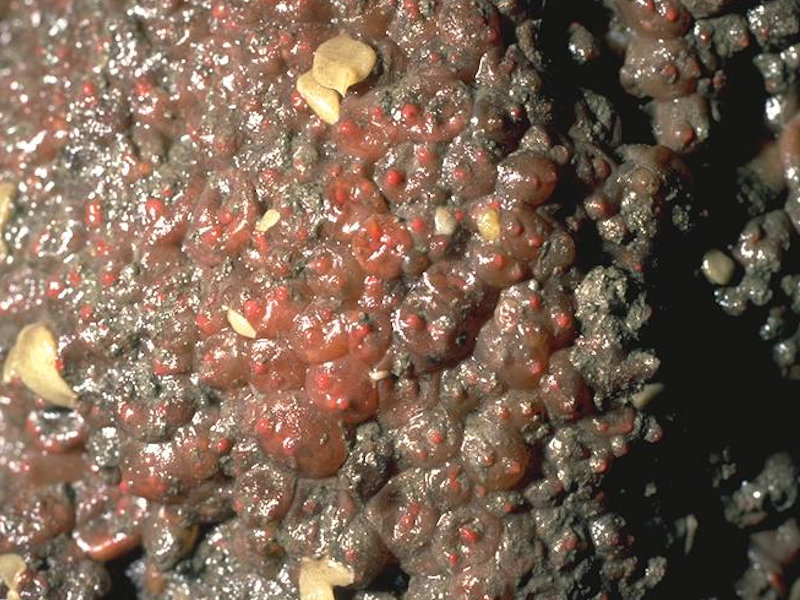

Overhanging bedrock on the lower shore, at cave entrances, and on inner walls of caves, subject to wave surge and low light levels, and characterized by a high density of small groups of the solitary ascidian Dendrodoa grossularia. The sponges Grantia compressa, Halichondria panicea and Hymeniacidon perleve are common on the rock surface, while the hydroid Dynamena pumila (normally found on fucoids) hangs in distinct form from overhanging rock. Found on the rock surface are the calcareous tube-forming polychaetes Spirorbis spp. and Spirobranchus spp. along with the barnacles Semibalanus balanoides. The anemone Actinia equina thrives in the permanently damp pits and crevices. Where sufficient light is available a sparse community of shade-tolerant red seaweeds. These include Membranoptera alata, Lomentaria articulata, Audouinella spp. and coralline crusts.

This biotope is found on lower shore overhangs and on the entrances and inner walls of lower shore caves, and usually dominates the available habitat. It is generally found above the BarCv biotope and may extend to the upper walls of caves. Some variation in the species composition of the individual caves must be expected depending on local conditions. (Information taken from Connor et al., 2004; JNCC, 2015).

Depth range

Lower shoreAdditional information

-

Listed By

Sensitivity review

Sensitivity characteristics of the habitat and relevant characteristic species

This sub-biotope LR.FLR.CvOv.SpR.Den is found further into caves than LR.FLR.CvOv.SpR, on shaded overhangs, cave entrances and the inner walls of caves (Connor et al., 2004). The sub-biotope is typically shaded, resulting in limited (or no) algal presence and is characterized by dense colonies of the ascidian Dendrodoa grossularia. The sponges Grantia compressa, Halichondria panicea and Hymeniacidon perleve are common on the rock surface, while the hydroid Dynamena pumila (normally found on fucoids) hangs in distinct form from overhanging rock. Calcareous tube-forming polychaetes Spirorbis spp. and Spirobranchus spp. are found on the rock surface along with the barnacles Semibalanus balanoides. The anemone Actinia equina thrives in the permanently damp pits and crevices. If sufficient light is available a sparse community of shade-tolerant red seaweeds can occur which includes Membranoptera alata, Lomentaria articulata, Rhodothamniella spp. and coralline crusts.

The sub-biotope is dominated by abundant Dendrodoa grossularia which distinguishes the sub-biotope from its similar parent (LR.FLR.CvOv.SpR) and common sponges Grantia compressa, Halichondria panicea and Hymeniacidon perleve. Therefore, the sensitivity of the sub-biotope is based on the sensitivity of these characteristic species. The other characteristic species are opportunistic or common in the surrounding biotopes (e.g. barnacles and hydroids) and any shade-tolerant red algae will vary with location depending on light availability. However, the sensitivity of other species are highlighted where appropriate.

Resilience and recovery rates of habitat

Little information on sponge longevity and resilience was found. Reproduction can be asexual (e.g. budding) or sexual (Naylor, 2011) and individual sponges are usually hermaphrodites (Hayward & Ryland, 1994). Short-lived ciliated larvae are released via the aquiferous system of the sponges and metamorphosis follows settlement. Growth and reproduction are generally seasonal (Hayward & Ryland, 1994). Rejuvenation from fragments is also considered an important form of reproduction in sponges (Fish & Fish, 1996). Some sponges are known to be highly resilience to physical damage with an ability to survive severe damage, regenerate and reorganize to function fully again. However, this recoverability varies between species (Wulff, 2006). Many sponges recruit annually and growth can be rapid, with a lifespan of one to several years (Ackers, 1983). However, sponge longevity and growth has been described as highly variable depending on the species and environmental conditions (Lancaster et al., 2014). Erect sponges are generally long-lived and slow-growing, given their more complex nature than the smaller encrusting or cushion sponges. Marine sponges often harbour dense and diverse microbial communities, which can include bacteria, archaea and single-celled eukaryotes (fungi and microalgae). The microbial community can comprise up to 40% of sponge volume and may have a profound impact on host biology (Webster & Taylor, 2012).

Fowler & Laffoley (1993) monitored the marine nature reserves in Lundy and the Isles Scilly and found that several common sponges showed great variation in size and cover during the study period. Large colonies appeared and vanished at some locations. Some large encrusting sponges went through periods of both growth and shrinkage, with considerable changes taking place from year to year. For example, Cliona celata colonies generally grew extremely rapidly, doubling their size or more each year but, in some years an apparent shrinkage in size took place. In contrast, there were no obvious changes in the cover of certain unidentified thin encrusting sponges.

Hymeniacidon perleve is found in thin sheets, cushions and, rarely, as erect and branching forms. It is found from the Arctic to the Mediterranean from the littoral to the circalittoral (Ackers et al., 1992). Halichondria panicea is very polymorphic, varying from thin sheets, massive forms and cushions to branching forms. It crumbles readily and branches are brittle (breaking if bent through 20°). As an opportunistic species, it is found in a wide range of niches on rock or any other hard substratum (Ackers et al., 1992). Barthel (1986) reported that Halichondria panicea in the Kiel Bight went through annual cycles, with growth occurring between March and July. After July, a strong decline in mean individual weight occurred until the end of September. No change in individual weight was observed over winter, although a change in biochemical composition (condition index and protein, lipid and glycogen content) was noted. Reproductive activity occurred in August and September with young colonies appearing in early autumn. Adult Halichondria panicea degenerated and disintegrated after reproduction. Fish & Fish (1996), however, suggested a lifespan of about three years and Vethaak et al. (1982) reported that Halichondria panicea survived the winter in a normal, active state in the Oosterschelde. Fell & Lewandrowski (1981) observed the population dynamics of Halichondria spp. within an eelgrass bed in a lower estuary in Connecticut over two years. Large numbers of larval derived specimens developed on the eelgrass during the summer, and many of these sponges became sexually reproductive, further increasing the size of the population. However, mortality was high, and at the end of the summer, only a relatively small sponge population remained. Sexual reproduction by larva-derived specimens of Halichondria spp. occurred primarily after breeding by the parental generation had declined. The larva-derived sponges grew rapidly, and the percentage of specimens containing large, female reproductive elements increased with specimen size. Halichondria spp. exhibited an opportunistic life strategy with a ‘high rate of turnover’. Gaino et al. (2010) observed reproduction within two communities of Hymeniacidon perlevis (syn. Hymeniacidon perleve). The onset of gametogenesis seemed to be triggered by environmental parameters, amongst which water temperature constituted the most relevant factor statistically. It was reported that differentiation and growth of the sexual elements were asynchronous, with reproduction lasting five months for the females and three months for the males in the Mar Piccolo di Tarant, Italy, from the end of spring to the late summer. Afterwards, the sponges disappeared with no recovery evident up to the end of monitoring (up to late winter 2007). Thomassen & Riisgard (1995) described a number of studies looking at the growth rates of Halichondria spp. with rates of between 1% and 3.3% of total volume per day.

Dendrodoa grossularia is a small solitary ascidian, 1.5-2 cm diameter (Millar, 1954). Settlement occurs from April-June, individuals reach their maximum size by the following summer. Life expectancy is expected to be 18-24 months. Sexual maturity is reached about one year after larval settlement and the release of gametes occurs from spring-autumn, with peaks in early spring and another in late summer. Gamete release is reduced at temperatures above 15°C and totally suppressed above ca 20°C (Millar, 1954). Kenny & Rees (1994) observed Dendrodoa grossularia was able to recolonize rapidly following aggregate dredging. Following experimental dredging of a site off the English coast, which extracted an area of 1-2 m wide and 0.3-0.5 m deep, Dendrodoa grossularia was able to recolonize and attained 40% of pre-dredge abundance and 23% of biomass within eight months. This recovery rate combined with the ability of this species to reach sexual maturity within its first year suggests that Dendrodoa grossularia can recover from disturbance events within 2 years. The species has a life expectancy of 18-24 months so that abundant populations are maintained by regular annual recruitment.

The red algae have complex life histories and exhibit distinct morphological stages over the reproductive life history. Alternation occurs between asexual spore producing stages (tetrasporophytes) and male and female plants producing sexually. Life history stages can be morphologically different or very similar. Norton (1992) reviewed dispersal by macroalgae and concluded that dispersal potential is highly variable and that recruitment usually occurs on a much more local scale, typically within 10 m of the parent plant. Hence, it is expected that the algal turf would normally rely on recruitment from local individuals and that recovery of populations via spore settlement, where adults are removed, could be protracted. Rhodophyceae have non-flagellate, and non-motile spores that stick on contact with the substratum. Norton (1992) noted that algal spore dispersal is probably determined by currents and turbulent deposition. However, red algae produce large numbers of spores that may settle close to the adult especially where currents are reduced by an algal turf or in kelp forests. It is likely that this species could recolonize an area from adjacent populations within a short period in ideal conditions. However, since the dispersal range of spores is limited because the female does not release carpospores and needs to be close to the adult male population, recolonization from distant populations would probably take much longer.

Spirorbids are rapid colonizers but poor competitors and hence are maintained in this biotope by the physical disturbance. Recovery may be within as little as three months for these species, based on the rapid settlement on artificial panels (Saunders & Connell, 2001; James & Underwood, 1994). Sebens (1985, 1986) observed that calcareous tubeworms, encrusting bryozoans and erect hydroids and bryozoans covered scraped areas within 4 months in spring, summer and autumn. Similarly, Hiscock (1983) noted that a community, under conditions of scour and abrasion from stones and boulders moved by storms, developed into a community similar to this biotope, consisting of fast-growing species such as Spirobranchus (formerly Pomatoceros) triqueter. Off Chesil Bank, the epifaunal community dominated by Spirobranchus (as Pomatoceros) triqueter and Balanus crenatus decreased in cover in October as it was scoured away in winter storms, but recolonized in May to June (Gorzula, 1977). Warner (1985) reported that the community did not contain any persistent individuals but that recruitment was sufficiently predictable to result in a dynamic stability.

On rocky shores, barnacles are often quick to colonize available gaps, although a range of factors influence whether there is a successful episode of recruitment in a year to re-populate a shore following impacts. Bennell (1981) observed that barnacles that were removed when the surface rock was scraped off in a barge accident at Amlwch, North Wales, but returned to pre-accident levels within three years. Petraitis & Dudgeon (2005) also found that Semibalanus balanoides quickly recruited to experimentally cleared areas within the Gulf of Maine (previously been dominated by Ascophyllum nodosum) and were present and increasing in density a year after clearance. However, barnacle densities were fairly low (on average 7.6 % cover) as predation levels in smaller patches were high and heat stress in large areas may have killed several individuals (Petraitis et al., 2003). Following the creation of a new shore in the Moray Firth, Semibalanus balanoides did not recruit in large numbers until 4 years after shore creation (Terry & Sell, 1986). Successful recruitment of a high number of Semibalanus balanoides individuals to replenish the population may be episodic (Kendall et al., 1985). After settlement, the juveniles are subject to high levels of predation as well as dislodgement from waves and sand abrasion depending on the area of settlement. Semibalanus balanoides may live up to 4 years in higher areas of the shore (Wethey, 1985). Predation rates are variable (see Petraitis et al., 2003) and are influenced by several factors including the presence of algae (that shelters predators such as Nucella lapillus, and the shore crab, Carcinus maenas and the sizes of clearings (as predation pressure is higher near canopies (Petraitis et al., 2003). Local environmental conditions, including surface roughness (Hills & Thomason, 1998), wind direction (Barnes, 1956), shore height, wave exposure (Bertness et al., 1991) and tidal currents (Leonard et al., 1998) have been identified, among other factors, as factors affecting settlement of Semibalanus balanoides. Biological factors such as larval supply, competition for space, the presence of adult barnacles (Prendergast et al., 2009) and the presence of species that facilitate or inhibit settlement (Kendall, et al., 1985; Jenkins et al., 1999) also play a role in recruitment. Mortality of juveniles can be high but highly variable, with up to 90% of Semibalanus balanoides dying within ten days (Kendall et al., 1985). Presumably, these factors also influence the transport, supply and settlement of Chthamaus spp., Balanus crenatus and other species such as spirorbids that produce pelagic larvae.

Resilience assessment. Sebens (1985, 1986) found that ascidians, encrusting bryozoans and tube worms all achieved significant cover in less than a year following complete removal, and, together with Halichondria panicea, reached pre-clearance levels of cover after two years. Dendrodoa grossularia can reach sexual maturity within one year of growth and can recover rapidly following severe habitat alteration. Overall, resilience is assessed as ‘High’ (within two years) for all levels of impact, even where resistance is ‘None’, as it is likely that a similar community can develop rapidly. Shade-tolerant red algae may occur where adequate light is available but their abundance probably varies between sites and the biotope classification is not dependent on their presence.

Note: The resilience and the ability to recover from human induced pressures is a combination of the environmental conditions of the site, the frequency (repeated disturbances versus a one-off event) and the intensity of the disturbance. Recovery of impacted populations will always be mediated by stochastic events and processes acting over different scales including, but not limited to, local habitat conditions, further impacts and processes such as larval-supply and recruitment between populations. Full recovery is defined as the return to the state of the habitat that existed before impact. This does not necessarily mean that every component species has returned to its prior condition, abundance or extent but that the relevant functional components are present and the habitat is structurally and functionally recognisable as the initial habitat of interest. It should be noted that the recovery rates are only indicative of the recovery potential.

Hydrological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Temperature increase (local) [Show more]Temperature increase (local)Benchmark. A 5°C increase in temperature for one month, or 2°C for one year. Further detail EvidenceIntertidal species are exposed to extremes of high and low air temperatures during periods of emersion. They must also be able to cope with sharp temperature fluctuations over a short period during the tidal cycle. In winter, air temperatures are colder than the sea. Conversely, in summer air temperatures are much warmer than the sea. Species that occur in this intertidal biotope are therefore generally adapted to tolerate a range of temperatures. The characterizing sponges Halichondria panacea and Hymeniacidon perleve are widely distributed across the coasts of the British Isles and are all found from the Channel Isles to northern Scotland (NBN, 2015). Berman et al. (2013) monitored sponge communities off Skomer Island, UK, over three years with all characterizing sponges for this biotope assessed. Seawater temperature, turbidity, photosynthetically active radiation and wind speed were all recorded during the study. It was concluded that, despite changes in species composition, primarily driven by the non-characterizing Hymeraphia, Stellifera and Halicnemia patera, no significant difference in sponge density was recorded in all sites studied. Morphological changes most strongly correlated with a mixture of water visibility and temperature. Lemoine et al. (2007) studied the effects of thermal stress on the holobiont of the sponge Halichondria bowerbanki collected from Virginia, USA. Whilst no apparent change in density or diversity of symbionts was detected over the range of temperatures (29°C, 30°C and 31°C), the presence of particular symbionts was temperature dependent. Barthel (1986) reported that reproduction and growth in Halichondria panicea in the Kiel Bight were primarily driven by temperature, with higher temperatures corresponding with the highest growth. For the ascidian Dendrodoa grossularia, gamete release occurs from spring-autumn, with peaks in early spring and another in late summer. Gamete release is reduced at temperatures above 15°C and suppressed completely above 20°C (Millar, 1954). No information was found on the upper temperature threshold of mature Dendrodoa grossularia. Whilst widespread throughout the British Isles (NBN, 2015), Dendrodoa grossularia is close to its southern limit and a dramatic increase in temperature outside the normal range for the UK may cause mortality. The distribution of the key characterizing species, Semibalanus balanoides is ‘northern’ with their range extending to the Arctic circle. Populations in the southern part of England are relatively close to the southern edge of their geographic range. Long-term time series show that successful recruitment of Semibalanus balanoides is correlated to sea temperatures (Mieszkowska et al., 2014) and that due to recent warming its range has been contracting northwards. Temperatures above 10 to 12°C inhibit reproduction (Barnes, 1957, 1963; Crisp & Patel, 1969) and laboratory studies suggest that temperatures at or below 10°C for 4-6 weeks are required in winter for reproduction, although the precise threshold temperatures for reproduction are not clear (Rognstad et al., 2014). Observations of recruitment success in Semibalanus balanoides throughout the south-west of England, strongly support the hypothesis that an extended period (4-6 weeks) of sea temperatures <10°C is required to ensure a good supply of larvae (Rognstad et al., 2014; Jenkins et al., 2000). During periods of high reproductive success, linked to cooler temperatures, the range of barnacles has been observed to increase, with range extensions in the order of 25 km (Wethey et al., 2011), and 100 km (Rognstad et al., 2014). Increased temperatures are likely to favour chthamalid barnacles or Austrominius modestus in the sheltered variable salinity biotopes rather than Semibalanus balanoides (Southward et al., 1995). Sensitivity assessment. The typical surface water temperatures around the UK coast vary seasonally from 4-19°C (Huthnance, 2010). The biotope is considered to tolerate a 2°C increase in temperature for a year. However, an acute high temperature event in the summer would approach the upper tolerance of some species and may result in some mortality. Therefore, resistance is assessed as ‘Medium’, resilience as ‘High’ and the sensitivity of the biotope is assessed as ‘Low’. | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Temperature decrease (local) [Show more]Temperature decrease (local)Benchmark. A 5°C decrease in temperature for one month, or 2°C for one year. Further detail EvidenceMany intertidal species are tolerant of freezing conditions as they are exposed to extremes of low air temperatures during periods of emersion. They must also be able to cope with sharp temperature fluctuations over a short period of time during the tidal cycle. In winter, air temperatures are colder than the sea. Conversely, in summer air temperatures are much warmer than the sea. Species that occur in the intertidal are therefore generally adapted to tolerate a range of temperatures, with the width of the thermal niche positively correlated with the height of the shore (Davenport & Davenport, 2005). The characterizing sponges Halichondria panacea and Hymeniacidon perleve are widely distributed across the coasts of the British Isles and are found from the Channel Isles to northern Scotland (NBN, 2015). Berman et al. (2013) monitored sponge communities off Skoma Island, UK, over three years with all characterizing sponges for this biotope assessed. Seawater temperature, turbidity, photosynthetically active radiation and wind speed were all recorded during the study. It was concluded that, despite changes in species composition, primarily driven by the non-characterizing Hymeraphia Stellifera and Halicnemia patera, no significant difference in sponge density was recorded in all sites studied. Morphological changes most strongly correlated with a mixture of visibility and temperature. Crisp (1964) studied the effects of an unusually cold winter (1962-63) on the marine life in Britain, including Porifera in North Wales. Whilst difficulty in distinguishing between mortality and delayed development was noted, Crisp found that Halichondria panicea was wholly or partly killed by frost and Hymeniacidon perleve was unusually rare. Barthel (1986) reported that Halichondria panicea in the Kiel Bight degenerated and disintegrated after reproduction before winter, however, young colonies were observed from September. However, Dendrodoa grossularia has been recorded as an abundant component of benthic fauna in Nottinghambukta, Svalbard (Różycki & Gruszczyński, 1991). Sensitivity assessment. There is evidence of sponge mortality at extremely low temperatures in the British Isles. Given this evidence, it is likely that cooling of 5°C for a month could affect the characterizing sponges, and resistance has been assessed as ‘Medium’ with a resilience of ‘High’. Sensitivity has, therefore, been assessed as ‘Low’ at the benchmark level. | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Salinity increase (local) [Show more]Salinity increase (local)Benchmark. A increase in one MNCR salinity category above the usual range of the biotope or habitat. Further detail EvidenceThis biotope is recorded in full salinity (30-35 ppt) habitats (Connor et al., 2004) and, therefore, the sensitivity assessment considers an increase from full salinity to >40 ppt. Biotopes found in the intertidal will naturally experience fluctuations in salinity where evaporation increases salinity and inputs of rainwater expose individuals to freshwater. Species found in the intertidal are, therefore, likely to have some form of behavioural or physiological adaptations to changes in salinity. Barnes & Barnes (1974) found that larvae from six barnacle species including Balanus crenatus, Chthamalus stellatus and Semibalanus (as Balanus) balanoides, completed their development to nauplii larvae at salinities between 20-40‰ (some embryos exposed at later development stages could survive at higher and lower salinities). Balanus crenatus occurs in estuarine areas and is, therefore, adapted to variable salinity (Davenport, 1976). When subjected to sudden changes in salinity Balanus crenatus closes its opercular valves so that the blood is maintained temporarily at a constant osmotic concentration (Davenport, 1976). Edyvean & Ford (1984b) suggest that populations of Lithophyllum incrustans are affected by temperature changes and salinity and that temperature and salinity ‘shocks’ induce spawning but no information on thresholds was provided (Edyvean & Ford, 1984b). Populations of Lithophyllum incrustans were less stable in rockpools with a smaller volume of water that were more exposed to temperature and salinity changes due to lower buffering capacity. Sexual plants (or the spores that give rise to them) were suggested to be more susceptible than asexual plants to extremes of local environmental variables (temperature, salinity etc.) as they occur with greater frequency at sites where temperature and salinity were more stable (Edyvean & Ford, 1984b). No evidence for Halichondria panicea or other characteristic sponges, Dendrodoa grossularia or other epifauna in hypersaline conditions was found. Sensitivity assessment. Although some increases in salinity may be tolerated by the associated species present these are generally short-term and mitigated during tidal inundation. However, no direct evidence was found to assess sensitivity to this pressure and 'No evidence' is recorded. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Salinity decrease (local) [Show more]Salinity decrease (local)Benchmark. A decrease in one MNCR salinity category above the usual range of the biotope or habitat. Further detail EvidenceThe characterizing sponge species Halichondria panicea and Hymeniacidon perleve occur in harbours and estuaries (Ackers et al., 1992) and have both been recorded in biotopes of variable salinity (Connor et al., 2004). Dendrodoa grossularia has been recorded as an abundant component of benthic fauna in Nottinghambukta, Svalbard where salinity can range between 6 and 20‰ (Różycki & Gruszczyński, 1991). Barnacles can survive periodic emersion in freshwater, e.g. from rainfall or freshwater run-off, by closing their opercular valves (Foster, 1971b). They can also withstand large changes in salinity over moderately long periods of time by falling into a "salt sleep". In this state, motor activity ceases and respiration falls, enabling animals to survive in fresh water for three weeks (Barnes, 1953). Semibalanus balanoides can tolerate salinities down to 12 psu, below which cirral activity ceases (Foster, 1970). Spirobranchus triqueter has not been recorded from brackish or estuarine waters. Therefore, it is likely that the species will be very intolerant of a decrease in salinity. However, Dixon (1985, cited in Riley & Ballerstedt, 2005) views the species as able to withstand significant reductions in salinity. The degree of reduction in salinity and time that the species could tolerate those levels were not recorded. Therefore, there is insufficient information available to assess the intolerance of Spirobranchus triqueter to a reduction in salinity and the assessment is based on its presence in the biotope CR.MCR.EcCr.UrtScr which occurs in variable salinity (as well as full) habitats (Connor et al., 2004). Sensitivity assessment. The majority of the species in the biotope have been recorded in areas of low salinity (such as estuaries). Although the overall nature of the biotope would probably be unaffected, some species may experience some mortality. Therefore, resistance is assessed as ‘Medium’ but with 'Low' confidence, resilience is probably ‘High’ and sensitivity is assessed as ‘Low’. | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Water flow (tidal current) changes (local) [Show more]Water flow (tidal current) changes (local)Benchmark. A change in peak mean spring bed flow velocity of between 0.1 m/s to 0.2 m/s for more than one year. Further detail EvidenceThe biotopes assessed occur in moderate to negligible tidal flows (0-1.5 m/sec). These biotopes occur on overhangs and caves that are partially sheltered from direct wave action, in moderately wave exposed to wave sheltered shores (Connor et al., 2004). Riisgard et al. (1993) discussed the low energy cost of filtration for sponges and concluded that passive current-induced filtration may be insignificant for sponges. Pumping and filtering occur in choanocyte cells that generate water currents in sponges using flagella (De Vos et al., 1991). Sensitivity assessment. All the biotopes within this complex (CvOv.SpR) are found on caves and overhangs. A significant increase or decrease in wave action could probably result in a fundamental change to the nature of the biotope due to scour, especially where the biotope occurs close to the base of the overhang or cave. Water flow is probably important for suspension feeders to supply food and remove wastes. However, wave action is probably the most important contributor to water movement in these biotopes. Hence, changes in water flow at the benchmark level (0.1-0.2 m/s) are unlikely to be significant enough to alter the biotope. Therefore, resistance is, assessed as ‘High’, resilience is ‘High’ and the biotope is ‘Not sensitive’ at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Emergence regime changes [Show more]Emergence regime changesBenchmark. 1) A change in the time covered or not covered by the sea for a period of ≥1 year or 2) an increase in relative sea level or decrease in high water level for ≥1 year. Further detail EvidenceEmergence regime is a key factor structuring this (and other) intertidal biotopes. Increased emergence may reduce habitat suitability for characterizing species through greater exposure to desiccation and reduced feeding opportunities for filter feeders including spirorbids, barnacles, sponges and anemones which feed when immersed. Semibalanus balanoides is less tolerant of desiccation stress than Chthamalus barnacle species and changes in emergence may, therefore, lead to species replacement and the development of a Chthamalus sp. dominated biotope, more typical of the upper shore may develop. It should be noted that moisture from wave surge is considered important in maintaining faunal abundance (Connor et al., 2004). Changes in emergence may, therefore, eventually lead to the replacement of this biotope to one more tolerant of desiccation. Decreased emergence would reduce desiccation stress and allow the attached suspension feeders more feeding time. Predation pressure on barnacles and limpets is likely to increase where these are submerged for longer periods and to prevent the colonization of lower zones. Semibalanus balanoides was able to extend its range into lower zones when protected from predation by the dogwhelk, Nucella lapillus (Connell, 1961). Mobile species present within the biotope would be able to relocate to preferred shore levels. Where decreased emergence leads to increased abrasion and scour while immersed, the removal of fauna may lead to this biotope reverting to the more barren LR.FLR.CvOv.ScrFa. Corallina officinalis may occur at a range of shore heights depending on local conditions such as the degree of wave action (Dommasnes, 1969), shore topography, run-off and degree of shelter from canopy-forming macroalgae. At Hinkley Point (Somerset, England), for example, seawater run-off from deep pools high in the intertidal supports dense turfs of Corallina spp. lower on the shore (Bamber & Irving, 1993). Fronds are highly intolerant of desiccation and do not recover from a 15% water loss, which might occur within 40-45 minutes during a spring tide in summer (Wiedemann, 1994). Bleached corallines were observed 15 months after the 1964 Alaska earthquake which elevated areas in Prince William Sound by 10 m. Similarly, increased exposure to air caused by upward movement of 15 cm due to nuclear tests at Amchitka Island, Alaska, adversely affected Corallina pilulifera (Johansen, 1974). During an unusually hot summer, Hawkins & Hartnoll (1985) observed damaged Corallina officinalis and other red algae. Littler & Littler (1984) suggested that the basal crustose stage is adaptive, allowing individuals to survive periods of physical stress as well as physiological stress such as desiccation and heating. The basal crust stage may persist for extended periods with frond regrowth occurring when conditions are favourable. Sensitivity assessment. This biotope occurs from the mid-littoral to the sublittoral fringe. Increased emergence may reduce habitat suitability for characterizing species through greater exposure to desiccation and reduced feeding opportunities for the faunal community while decreased emergence would reduce desiccation stress and allow the attached epifauna more feeding time, although may result in succession. As emergence is a key factor structuring the distribution of species on the shore, resistance to a change in emergence (increase or decrease) is assessed as ‘Low’. Resilience is assessed as ‘High’, and sensitivity is, therefore, assessed as 'Low'. | LowHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Wave exposure changes (local) [Show more]Wave exposure changes (local)Benchmark. A change in near shore significant wave height of >3% but <5% for more than one year. Further detail EvidenceThese biotopes occur on overhangs and caves that are partially sheltered from direct wave action, in moderately wave exposed to wave sheltered shores (Connor et al., 2004). Changes in wave action will probably affect the degree of splash and spray, and hence moisture, desiccation and salinity experienced by the biotopes. Therefore, a change in wave exposure will probably affect the upper and lower extent of the biotopes and result in loss of extent. The effects of wave surge are considered to be one factor differentiating between SpR.Den and SpByAs biotopes. Increased wave height could result in increased scour which may result in a decline in abundance of the characterizing species. Sensitivity assessment. This biotope is recorded as occurring from exposed to sheltered conditions but local conditions are likely to be an important factor in assessing effects. These biotopes are found under overhangs and on the walls of caves which may afford some protection to the characterizing species. A significant change in wave exposure would probably result in a fundamental change to the nature of the biotope. However, at the benchmark level, changes are unlikely to be significant and resistance is, therefore, assessed as ‘High’, resilience is ‘High’ and the biotope is ‘Not sensitive’ at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Chemical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Transition elements & organo-metal contamination [Show more]Transition elements & organo-metal contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed but evidence is presented where available. No information was found concerning the effects of heavy metals on encrusting coralline algae. Bryan (1984) suggested that the general order for heavy metal toxicity in seaweeds is: organic Hg> inorganic Hg > Cu > Ag > Zn> Cd> Pb. Contamination at levels greater than the pressure benchmark may adversely impact the biotope. Cole et al. (1999) reported that Hg was very toxic to macrophytes. The sub-lethal effects of Hg (organic and inorganic) on the sporelings of an intertidal red algae, Plumaria elegans, were reported by Boney (1971). Total growth inhibition was caused by 1 ppm Hg. Barnacles accumulate heavy metals and store them as insoluble granules (Rainbow, 1987). Pyefinch & Mott (1948) recorded a median lethal concentration of 0.19 mg/l copper and 1.35 mg/l mercury for Balanus crenatus over 24 hours. Barnacles may tolerate fairly high level of heavy metals in nature, for example, they are found in Dulas Bay, Anglesey, where copper reaches concentrations of 24.5 µg/l, due to acid mine waste (Foster et al., 1978). While some sponges, such as Cliona spp. have been used to monitor heavy metals by looking at the associated bacterial community (Marques et al., 2007; Bauvais et al., 2015), no literature on the effects of transition element or organo-metal pollutants on the characterizing sponges could be found. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Hydrocarbon & PAH contamination [Show more]Hydrocarbon & PAH contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed but any evidence is presented where available. Tethya lyncurium concentrated BaP (benzo[a ]pyrene) to 40 times the external concentration and no significant repair of DNA was observed in the sponges, which, in higher animals, would likely lead to cancers. As sponge cells are not organized into organs the long-term effects are uncertain (Zahn et al., 1981). No information was found on the intolerance of the characterizing sponges or barnacles to hydrocarbons. However, other littoral barnacles generally have a high tolerance to oil (Holt et al., 1995) and were little impacted by the Torrey Canyon oil spill (Smith, 1968). Ignatiades & Becacos-Kontos (1970) found that Ciona intestinalis can resist the toxicity of oil-polluted water and ascidians are frequently found in polluted habitats such as marinas and harbours, etc. (Carver et al., 2006) as well as Ascidia mentula (Aneiros et al., 2015). Ryland & De Putron (1998) found no detectable damage to under-boulder communities, which are similar to some overhang communities, in Watwick Bay, Pembrokeshire following the Sea Empress oil spill. Part of the resistance to effects might be because oil does not settle onto overhanging surfaces. However, some species, especially gastropods are likely to be narcotised and killed and some damage is likely. Return to a previous species composition would occur from new settlement from larval sources although some gastropods have no or only a short dispersal phase so that recovery will be slow. O'Brien & Dixon (1976) suggested that red algae were the most sensitive group of algae to oil or dispersant contamination, possibly due to the susceptibility of phycoerythrins to destruction, but that the filamentous forms were the most sensitive. Laboratory studies of the effects of oil and dispersants on several red algae species, including Palmaria palmata (Grandy, 1984 cited in Holt et al., 1995) concluded that they were all sensitive to oil/ dispersant mixtures, with little differences between adults, sporelings, diploid or haploid life stages. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Synthetic compound contamination [Show more]Synthetic compound contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed but any evidence is presented where available. Barnacles have a low resilience to chemicals such as dispersants, dependent on the concentration and type of chemical involved (Holt et al., 1995). Balanus crenatus was the dominant species on pier pilings at a site subject to urban sewage pollution (Jakola & Gulliksen, 1987). Hoare & Hiscock (1974) found that Balanus crenatus survived near to an acidified halogenated effluent discharge where many other species were killed, suggesting a high tolerance to chemical contamination. Little information is available on the impact of endocrine disrupters on adult barnacles. Holt et al. (1995) concluded that barnacles are fairly sensitive to chemical pollution. Cole et al. (1999) suggested that herbicides, such as simazina and atrazine were very toxic to macrophytes. Hoare & Hiscock (1974) noted that all red algae were excluded from Amlwch Bay, Anglesey, by acidified halogenated effluent discharge. Such evidence suggests Palmaria palmata has a high intolerance to synthetic chemicals at levels greater than the benchmark. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Radionuclide contamination [Show more]Radionuclide contaminationBenchmark. An increase in 10µGy/h above background levels. Further detail Evidence‘No evidence’ was found. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Introduction of other substances [Show more]Introduction of other substancesBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

De-oxygenation [Show more]De-oxygenationBenchmark. Exposure to dissolved oxygen concentration of less than or equal to 2 mg/l for one week (a change from WFD poor status to bad status). Further detail EvidenceThis biotope occurs in areas that are shallow and tidally flushed where re-oxygenation is likely so that the effects of any de-oxygenation events may be limited. However, this may mean that the species present have little exposure to low oxygen and may be sensitive to this pressure. Balanus crenatus, however, respires anaerobically so it can withstand some decrease in oxygen levels. When placed in wet nitrogen, where oxygen stress is maximal and desiccation stress is minimal, Balanus crenatus has a mean survival time of 3.2 days (Barnes et al., 1963) and this species is considered to be ‘Not sensitive’ to this pressure. Semibalanus balanoides can respire anaerobically, so they can tolerate some reduction in oxygen concentration (Newell, 1979). When placed in wet nitrogen, where oxygen stress is maximal and desiccation stress is low, Semibalanus balanoides have a mean survival time of 5 days (Barnes et al., 1963). Halichondria panicea has been reported to survive under oxygen levels as low as 0.5-4% saturation (ca 0.05-0.4 mg/l) for up to 10 days (Mills et al., 2014). Little information on the effects of oxygen depletion on macroalgae was found, although Kinne (1972) reports that reduced oxygen concentrations inhibit both photosynthesis and respiration which may affect growth and reproduction. The effects of decreased oxygen concentration equivalent of the benchmark would be greatest during the dark when the macroalgae are dependent on respiration. However, this biotope occurs in the intertidal and Palmaria palmata will be able to respire during periods of emersion. Sensitivity assessment. Based on evidence for the characterizing Semibalanus balanoides, Halichondria panicea and considering mitigation of de-oxygenation by water movements, this biotope is considered to have 'High' resistance and 'High' resilience (by default), and is, therefore, 'Not sensitive' at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Nutrient enrichment [Show more]Nutrient enrichmentBenchmark. Compliance with WFD criteria for good status. Further detail EvidenceThe benchmark is set at compliance with WFD criteria for good status, based on nitrogen concentration (UKTAG, 2014). 'Not sensitive' at the pressure benchmark that assumes compliance with good status as defined by the WFD. This pressure relates to increased levels of nitrogen, phosphorus and silicon in the marine environment compared to background concentrations. The nutrient enrichment of a marine environment leads to organisms no longer being limited by the availability of certain nutrients. The consequent changes in ecosystem functions can lead to the progression of eutrophic symptoms (Bricker et al., 2008), changes in species diversity and evenness (Johnston & Roberts, 2009) decreases in dissolved oxygen and uncharacteristic microalgae blooms (Bricker et al., 1999, 2008). Johnston & Roberts (2009) undertook a review and meta-analysis of the effect of contaminants on species richness and evenness in the marine environment. Of the 47 papers reviewed relating to nutrients as a contaminant, over 75% found that it had a negative impact on species diversity, <5% found increased diversity, and the remaining papers finding no detectable effect. Due to the ‘remarkably consistent’ effect of marine pollutants on species diversity, this finding is relevant to this biotope. It was found that any single pollutant reduced species richness by 30-50% within any of the marine habitats considered. These examples were almost entirely from the introduction of nutrients, either from aquaculture or sewage outfalls (Johnston & Roberts, 2009). Moderate nutrient enrichment, especially in the form of organic particulates and dissolved organic material, is likely to increase food availability for all the suspension feeders within the biotope. However, long-term or high levels of organic enrichment may result in eutrophication and have indirect adverse effects, such as increased turbidity, increased suspended sediment, increased risk of deoxygenation and the risk of algal blooms. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not sensitiveHelp |

Organic enrichment [Show more]Organic enrichmentBenchmark. A deposit of 100 gC/m2/yr. Further detail EvidenceOrganic enrichment leads to organisms no longer being limited by the availability of organic carbon. The consequent changes in ecosystem function can lead to the progression of eutrophic symptoms (Bricker et al., 2008), changes in species diversity and evenness (Johnston & Roberts, 2009) and decreases in dissolved oxygen and uncharacteristic microalgae blooms (Bricker et al., 1999, 2008). Indirect adverse effects associated with organic enrichment include increased turbidity, increased suspended sediment and the increased risk of deoxygenation. Johnston & Roberts (2009) undertook a review and meta-analysis of the effect of contaminants on species richness and evenness in the marine environment. Of the 49 papers reviewed relating to sewage as a contaminant, over 70% found that it had a negative impact on species diversity, <5% found increased diversity, and the remaining papers finding no detectable effect. It was found that any single pollutant reduced species richness by 30-50% within any of the marine habitats considered (Johnston & Roberts, 2009). Throughout their investigation, there were only a few examples where species richness was increased due to the anthropogenic introduction of a contaminant. These examples were almost entirely from the introduction of nutrients, either from aquaculture or sewage outfalls. The animals found within the biotope may be able to utilize the input of organic matter as food, or are likely to be tolerant of inputs at the benchmark level. Cabral-Oliveira et al. (2014) found that filter feeders including the barnacle Chthamalus montagui, were more abundant at sites closer to a sewage treatment works, as they could utilize the organic matter inputs as food. On the same shores, higher abundances of juvenile Patella sp. and lower abundances of adults were found closer to sewage inputs. Cabral-Oliveira et al. (2014) suggested the structure of these populations was due to increased competition closer to the sewage outfalls. Balanus crenatus and Spirobranchus triqueter were assigned to AMBI Group II described as 'species indifferent to enrichment, always present in low densities with non-significant variations with time, from an initial state to slight unbalance' (Gittenberger & Van Loon, 2011). Halichondria occurs in harbours and estuaries (Ackers et al., 1992) and may, therefore, tolerate high levels of organic carbon, although no specific evidence for this species was found, other sponges have been described in organically enriched environments. Fu et al. (2007) described Hymeniacidon perleve in aquaculture ecosystems in sterilized natural seawater with different concentrations of total organic carbon (TOC). At several concentrations between 52.9 and 335.13 mg/l), Hymeniacidon perleve removed 44–61% TOC during 24 h, with retention rates of ca 0.19–1.06 mg/hr per g-fresh sponge. Hymeniacidon perleve removed organic carbon excreted by Fugu rubripes with similar retention rates of ca 0.15 mg/h/ per g-fresh sponge, and the sponge biomass increased by 22.8%. Some of the characterizing species occur in harbours and estuaries, including Halichondria panicea (Ackers et al., 1992). There was some suggestion that there are possible benefits to the ascidians from increased organic content of water; 'ascidian richness’ in Algeciras Bay was found to increase in higher concentrations of suspended organic matter (Naranjo et al. 1996). The crusting coralline Lithophyllum incrustans was present at sites dominated by Ulva spp. in the Mediterranean exposed to high levels of organic pollution from domestic sewage (Arévalo et al., 2007). As turfs of red algae can trap large amounts of sediment the red algae are not considered sensitive to the sedimentation element of this pressure. Within trapped sediments, associated species and deposit feeders would be able to consume inputs of organic matter. Sensitivity assessment. It is not clear whether the pressure benchmark would lead to enrichment effects in this dynamic habitat. Water movement would disperse organic matter particles, mitigating the effect of this pressure. Based on the AMBI categorization (Borja et al., 2000, Gittenberger & Van Loon, 2011). Although species within the biotope may be sensitive to gross organic pollution resulting from sewage disposal and aquaculture, they are considered to have ‘High’ resistance to the pressure benchmark (which represents organic enrichment) and therefore ‘High’ resilience. The biotope is, therefore, assessed as ‘Not sensitive’. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Physical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Physical loss (to land or freshwater habitat) [Show more]Physical loss (to land or freshwater habitat)Benchmark. A permanent loss of existing saline habitat within the site. Further detail EvidenceAll marine habitats and benthic species are considered to have a resistance of ‘None’ to this pressure and to be unable to recover from a permanent loss of habitat (resilience is ‘Very low’). Sensitivity within the direct spatial footprint of this pressure is, therefore ‘High’. Although no specific evidence is described, confidence in this assessment is ‘High’ due to the incontrovertible nature of this pressure. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical change (to another seabed type) [Show more]Physical change (to another seabed type)Benchmark. Permanent change from sedimentary or soft rock substrata to hard rock or artificial substrata or vice-versa. Further detail EvidenceIf rock were replaced with sediment, this would represent a fundamental change to the physical character of the biotope and the species would be unlikely to recover. The biotope would be lost. Resistance to the pressure is considered ‘None’, and resilience ‘Very low’. Sensitivity has been assessed as ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical change (to another sediment type) [Show more]Physical change (to another sediment type)Benchmark. Permanent change in one Folk class (based on UK SeaMap simplified classification). Further detail Evidence‘Not relevant’ to biotopes occurring on bedrock. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Habitat structure changes - removal of substratum (extraction) [Show more]Habitat structure changes - removal of substratum (extraction)Benchmark. The extraction of substratum to 30 cm (where substratum includes sediments and soft rock but excludes hard bedrock). Further detail EvidenceThe species characterizing this biotope are epifauna or epiflora occurring on rock and would be sensitive to the removal of the habitat. However, extraction of rock substratum is considered unlikely and this pressure is considered to be ‘Not relevant’ to hard substratum habitats. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Abrasion / disturbance of the surface of the substratum or seabed [Show more]Abrasion / disturbance of the surface of the substratum or seabedBenchmark. Damage to surface features (e.g. species and physical structures within the habitat). Further detail EvidenceThe species characterizing this biotope occur on the rock and, therefore, have no protection from surface abrasion. For this assessment, the focus is on the effects of trampling and scour. Halichondria panicea is compressible but crumbly in texture and easily broken (Ackers et al, 1992) and is typically found in cryptic or semi-cryptic areas (Hayward & Ryland, 1995b). Abrasion events are therefore likely to remove the sponge, however, specific evidence was not found. Little information is available on the effects of abrasion on intertidal red algae. Brosnan & Crumrine (1994) found that the foliose red algae Mastocarpus papillatus was intolerant of moderate levels of trampling, but recovered rapidly. It should be noted that algal turf increased in abundance following trampling, although this may be due to reduced competition with barnacles. The effects of trampling (a source of abrasion) on barnacles appear to be variable with some studies not detecting significant differences between trampled and controlled areas (Tyler-Walters & Arnold, 2008). However, this variability may be related to differences in trampling intensities and abundance of populations studied. The worst-case incidence was reported by Brosnan & Crumrine (1994) who reported that a trampling pressure of 250 steps in a 20x20 cm plot one day a month for a period of a year significantly reduced barnacle cover at two study sites. Barnacle cover reduced from 66% to 7% cover in 4 months at one site and from 21% to 5% within 6 months at the second site. Overall barnacles were crushed and removed by trampling. Barnacle cover remained low until recruitment the following spring. Long et al. (2011) also found that heavy trampling (70 humans /km shoreline /h) led to reductions in barnacle cover. Single-step experiments provide a clearer, quantitative indication of sensitivity to direct abrasion. Povey & Keough (1991) in experiments on shores in Mornington peninsula, Victora, Australia, found that in single-step experiments 10 out of 67 barnacles, (Chthamlus antennatus about 3 mm long), were crushed. However, on the same shore, the authors found that limpets may be relatively more resistant to abrasion from trampling. After step and kicking experiments, few individuals of the limpet Cellana trasomerica, (similar size to Patella vulgata) suffered damage or relocated (Povey & Keough, 1991). One kicked limpet (out of 80) was broken and 2 (out of 80) limpets that were stepped on could not be relocated the following day (Povey & Keough, 1991). Trampling may lead to indirect effects on limpet populations, Bertocci et al. (2011) found that the effects of trampling on Patella sp. increased the temporal and spatial variability of in abundance. The experimental plots were sited on a wave-sheltered shore dominated by Ascophyllum nodosum. On these types of shore, trampling in small patches, that removes macroalgae and turfs, will indirectly enhance habitat suitability for limpets by creating patches of exposed rock for grazing. Off Chesil Bank, the epifaunal community dominated by Spirobranchus (as Pomatoceros) triqueter and Balanus crenatus decreased in cover in October as it was scoured away in winter storms, but recolonized in May to June (Gorzula, 1977). Warner (1985) reported that the community did not contain any persistent individuals but that recruitment was sufficiently predictable to result in a dynamic stability and a similar community, dominated by Spirobranchus (as Pomatoceros) triqueter, Balanus crenatus and Electra pilosa, (an encrusting bryozoan), was present in 1979, 1980 and 1983 (Riley & Ballerstedt, 2005). Shanks & Wright (1986), found that even small pebbles (<6 cm) that were thrown by wave action in Southern California shores could create patches in Chthamalus fissus aggregations and could smash owl limpets (Lottia gigantea). Average, estimated survivorship of limpets at a wave exposed site, with many loose cobbles and pebbles allowing greater levels of abrasion was 40% lower than at a sheltered site. Severe storms were observed to lead to an almost total destruction of local populations of limpets through abrasion by large rocks and boulders. Sensitivity assessment. The impact of surface abrasion will depend on the footprint, duration and magnitude of the pressure, however, persistent abrasion from scouring could result in a change to the similar biotope LR.FLR.CvOv.ScrFa (Connor et al., 2004). Therefore, resistance is assessed as ‘Low’ and resilience as ‘High’ so that sensitivity is assessed as ‘Low’. | LowHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Penetration or disturbance of the substratum subsurface [Show more]Penetration or disturbance of the substratum subsurfaceBenchmark. Damage to sub-surface features (e.g. species and physical structures within the habitat). Further detail EvidenceThe species characterizing this biotope group are epifauna or epiflora occurring on rock which is resistant to subsurface penetration. The assessment for abrasion at the surface only is therefore considered to equally represent sensitivity to this pressure. This pressure is ‘Not relevant’ to hard rock biotopes. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Changes in suspended solids (water clarity) [Show more]Changes in suspended solids (water clarity)Benchmark. A change in one rank on the WFD (Water Framework Directive) scale e.g. from clear to intermediate for one year. Further detail EvidenceIntertidal biotopes will only be exposed to this pressure when submerged during the tidal cycle and thus may have limited exposure. Siltation, which may be associated with increased suspended solids and the subsequent deposition of these is assessed separately (see siltation pressures). In general, increased suspended particles reduce light penetration and increase scour and deposition. They may enhance food supply to filter or deposit feeders (where the particles are organic in origin) or decrease feeding efficiency (where the particles are inorganic and require greater filtration efforts). Increases in the cover of robust, sediment trapping, turf-forming algae at the expense of canopy-forming species have been observed worldwide in temperate systems and has been linked to increased suspended solids linked to human activities worldwide (Airoldi, 2003). Despite increased sediment being considered to have a negative impact on suspension feeders (Gerrodette & Flechsig, 1979), many encrusting sponges appear to be able to survive in highly sediment conditions (Schönberg, 2015; Bell & Barnes, 2000; Bell & Smith, 2004). Some of the characterizing species occur in harbours and estuaries, including Halichondria spp. and Hymeniacidon perleve (Ackers et al., 1992) which are likely to experience high turbidity events. Halichondria panicea has a cleaning mechanism sloughing off its complete outer tissue layer together with any debris (Barthel & Wolfrath, 1989). There is, however, an energetic cost in cleaning resulting in reduced growth. For short-lived species, such as the star ascidian Botryllus schlosseri, reduced growth could prove fatal. Available evidence indicates that Spirobranchus triqueter is tolerant of a wide range of suspended sediment concentrations (Riley & Ballerstedt, 2005). Stubbings & Houghton (1964) recorded Spirobranchus (as Pomatoceros) triqueter in Chichester harbour, which is a muddy environment. However, Spirobranchus (as Pomatoceros) triqueter has been noted to also occur in areas where there is little or no silt present (Price et al., 1980). Sensitivity assessment. An increase in suspended sediment could result in an increase in scour due to wave action and tidal flow and potentially clog the filtration apparatus of suspension-feeders. Therefore, resistance is assessed as ‘Medium’, to indicate the potential for some mortality due to the scour effect as the sediment is removed. Resilience is assessed as ‘High’ and sensitivity as ‘Low’. | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Smothering and siltation rate changes (light) [Show more]Smothering and siltation rate changes (light)Benchmark. ‘Light’ deposition of up to 5 cm of fine material added to the seabed in a single discrete event. Further detail EvidenceThis biotope occurs under overhangs and at the entrance to caves and the majority of the examples of this biotope are, therefore, unlikely to be affected by an increase in sediment deposition. This being said, where the biotope does occur on the shallow or flat, lower, surfaces at cave entrances or are adjacent on the surface, mortality could occur, depending on the level and rate of removal of the sediment. Despite sediment being considered to have a negative impact on suspension feeders (Gerrodette & Flechsig, 1979), many encrusting sponges appear to be able to survive in highly sedimented conditions, and in fact, many species prefer such habitats (Schönberg, 2015; Bell & Barnes, 2000; Bell & Smith, 2004). Whilst complete smothering may result in loss of the sponges, the biotope often occurs on cave walls and ceilings and thus burial is unlikely. In a review of the effects of sedimentation on rocky coast assemblages, Airoldi (2003) outlined the evidence for the sensitivity of encrusting coralline algae to sedimentation. The reported results are contradictory with some authors suggesting that coralline algae are negatively affected by sediments while others report that encrusting corallines are often abundant or even dominant in a variety of sediment impacted habitats (Airoldi, 2003). Crustose corallines have been reported to survive under a turf of filamentous algae and sediment for 58 days (the duration of the experiment) in the Galapagos (species not identified, Kendrick, 1991). The crustose coralline Hydrolithon reinboldii has also been reported to survive deposition of silty sediments on subtidal reefs off Hawaii (Littler, 1973). In an experimental study, Balata et al. (2007) enhanced sedimentation on experimental plots in the Mediterranean (close to Tuscany) by adding 400 g of fine sediment every 45 days on plots of 400 cm2 for 1 year. Nearby sites with higher and lower levels of sedimentation were assessed as control plots. Some clear trends were observed. Crustose corallines declined at medium and high levels of sedimentation (Balata et al., 2007). The experiment relates to chronic low levels of sedimentation rather than a single acute event, as in the pressure benchmark, however, the trends observed are considered to have some relevance to the pressure assessment. Dendrodoa grossularia is a small ascidian, capable of reaching a size of approx. 8.5 mm (Millar, 1954) and is, therefore, likely to be inundated by deposition of 5 cm of sediment. If inundation is long-lasting then the understorey community may be adversely affected. Sensitivity assessment. Overall, the biotope is unlikely to be affected by smothering, unless adjacent to the sediment surface. Increase in sediment could result in scour following suspension due to wave and tidal flow. Removal of the sediment is likely to be rapid. Therefore, resistance is assessed as ‘Medium’, mainly due to the scour effect as the sediment is removed, so that resilience is assessed as ‘High’ and sensitivity as ‘Low’. | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Smothering and siltation rate changes (heavy) [Show more]Smothering and siltation rate changes (heavy)Benchmark. ‘Heavy’ deposition of up to 30 cm of fine material added to the seabed in a single discrete event. Further detail EvidenceThis biotope occurs under overhangs and at the entrance to caves and the majority of the examples of this biotope are therefore unlikely to be affected by an increase in sediment deposition. This being said, where the biotope does occur on the shallow or flat, lower, surfaces at cave entrances, mortality could occur, depending on the level and rate of removal of the sediment. Despite sediment being considered to have a negative impact on suspension feeders (Gerrodette & Flechsig 1979), many encrusting sponges appear to be able to survive in highly sedimented conditions, and in fact, many species prefer such habitats (Schönberg, 2015; Bell & Barnes 2000; Bell & Smith, 2004). Whereas complete smothering may result in loss of the sponges, the biotope often occurs on cave walls and ceilings and thus burial is unlikely. In a review of the effects of sedimentation on rocky coast assemblages, Airoldi (2003) outlined the evidence for the sensitivity of encrusting coralline algae to sedimentation. The reported results are contradictory with some authors suggesting that coralline algae are negatively affected by sediments while others report that encrusting corallines are often abundant or even dominant in a variety of sediment impacted habitats (Airoldi, 2003 and references). Crustose corallines have been reported to survive under a turf of filamentous algae and sediment for 58 days (the duration of the experiment) in the Galapagos (species not identified, Kendrick, 1991). The crustose coralline Hydrolithon reinboldii, has also been reported to survive deposition of silty sediments on subtidal reefs off Hawaii (Littler, 1973). In an experimental study, Balata et al. (2007) enhanced sedimentation on experimental plots in the Mediterranean (close to Tuscany) by adding 400 g of fine sediment every 45 days on plots of 400 cm2 for one year. Nearby sites with higher and lower levels of sedimentation were assessed as control plots. Some clear trends were observed. Crustose corallines declined at medium and high levels of sedimentation (Balata et al., 2007). The experiment relates to chronic low levels of sedimentation rather than a single acute event, as in the pressure benchmark, however, the trends observed are considered to have some relevance to the pressure assessment. Dendrodoa grossularia is a small ascidian, capable of reaching a size of approx 8.5 mm (Millar, 1954) and is, therefore, likely to be inundated by deposition of 30 cm of sediment. If inundation is long-lasting then the understorey community may be adversely affected. Sensitivity assessment. Overall, the biotope is unlikely to be affected by smothering, unless adjacent to the sediment surface. Increase in sediment could result in scour following suspension due to wave and tidal flow. Removal of the sediment is likely to be rapid. Therefore, resistance is assessed as ‘Medium’, mainly due to the scour effect as the sediment is removed, so that resilience is assessed as ‘High’ and sensitivity as ‘Low’. | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Litter [Show more]LitterBenchmark. The introduction of man-made objects able to cause physical harm (surface, water column, seafloor or strandline). Further detail EvidenceNot assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Electromagnetic changes [Show more]Electromagnetic changesBenchmark. A local electric field of 1 V/m or a local magnetic field of 10 µT. Further detail Evidence‘No evidence’ was found. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Underwater noise changes [Show more]Underwater noise changesBenchmark. MSFD indicator levels (SEL or peak SPL) exceeded for 20% of days in a calendar year. Further detail EvidenceWhilst no evidence could be found for the effect of noise or vibrations on the characterizing species of these biotopes, it is unlikely that these species have the facility for detecting or noise vibrations. The characterizing sponges are unlikely to respond to noise or vibrations and resistance is, therefore, assessed as ‘High’, resilience as ‘High’ and sensitivity as ‘Not sensitive’. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Introduction of light or shading [Show more]Introduction of light or shadingBenchmark. A change in incident light via anthropogenic means. Further detail EvidenceThese biotopes are characteristic of shaded or dark, moist caves, presumably because green algae would out-compete the dominant species at higher light levels. If artificial lighting was introduced to a cave where this biotope occurred, then it might adversely affect the biotopes by promoting green algal growth. Increased shade might reduce light levels below those needed for the algae to survive. While an increase or decrease in light could affect the algae present within this biotope, growth ceases for a number of red algae (including Chrondrus crispus) below ca 1.0 μmol m-2l-1 (ca 50 Lux), whereas this value is 2 μmol m-2l-1 (ca 100 Lux) for green algae (Leukart & Lüning, 1994). Jones et al. (2012) found that many sponges, particularly encrusting species, preferred vertical or shaded bedrock to open, light surfaces. However, it is possible that this relates to decreased competition with algae. No evidence could be found for the effect of light on the other faunal species present within these biotopes but it is unlikely that they would be impacted. Sensitivity assessment. An increase at the benchmark level (0.1 Lux) is unlikely to be significant. Shading may result in loss of the sparse red algal community. However, an increase in artificial light or the removal of already shading structures may allow more red algae to grow, reverting the biotope to CvOv.SpR in the affected areas and the loss of this sub-biotope (CvOv.Spr.Den). Therefore, resistance to this pressure is assessed as 'Low' and resilience as 'High' and sensitivity is assessed as ‘Low'. | LowHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Barrier to species movement [Show more]Barrier to species movementBenchmark. A permanent or temporary barrier to species movement over ≥50% of water body width or a 10% change in tidal excursion. Further detail EvidenceBarriers that reduce the degree of tidal excursion may alter larval supply to suitable habitats from source populations. Conversely, the presence of barriers may enhance local population supply by preventing the loss of larvae from enclosed habitats. Barriers and changes in tidal excursion are not considered relevant to the characterizing crusting corallines and red algal turfs as species dispersal is limited by the rapid rate of settlement and vegetative growth from bases rather than reliance on recruitment from outside of populations. Resistance to this pressure is assessed as 'High' and resilience as 'High' by default. This biotope is therefore considered to be 'Not sensitive'. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Death or injury by collision [Show more]Death or injury by collisionBenchmark. Injury or mortality from collisions of biota with both static or moving structures due to 0.1% of tidal volume on an average tide, passing through an artificial structure. Further detail EvidenceThe pressure definition is not directly applicable to caves or overhangs, so ‘Not relevant’ has been recorded. Collision via ship groundings or terrestrial vehicles is possible but the effects are probably similar to those of abrasion above. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Visual disturbance [Show more]Visual disturbanceBenchmark. The daily duration of transient visual cues exceeds 10% of the period of site occupancy by the feature. Further detail Evidence‘Not relevant’ | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Biological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Genetic modification & translocation of indigenous species [Show more]Genetic modification & translocation of indigenous speciesBenchmark. Translocation of indigenous species or the introduction of genetically modified or genetically different populations of indigenous species that may result in changes in the genetic structure of local populations, hybridization, or change in community structure. Further detail Evidence‘No evidence’ was found. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Introduction of microbial pathogens [Show more]Introduction of microbial pathogensBenchmark. The introduction of relevant microbial pathogens or metazoan disease vectors to an area where they are currently not present (e.g. Martelia refringens and Bonamia, Avian influenza virus, viral Haemorrhagic Septicaemia virus). Further detail EvidenceDiseased encrusting corallines were first observed in the tropics in the early 1990s when the bacterial pathogen Coralline Lethal Orange Disease (CLOD) was discovered (Littler & Littler, 1995). All species of articulated and crustose species tested to date are easily infected by CLOD and it has been increasing in occurrence at sites where is was first observed and spreading through the tropics. Another bacterial pathogen causing a similar CLOD disease has been observed with a greater distribution and a black fungal pathogen first discovered in American Samoa has been dispersing (Littler & Littler, 1998). An unknown pathogen has also been reported to lead to white ‘target-shaped’ marks on corallines, again in the tropics (Littler et al., 2007). No evidence was found that these pathogens are impacting temperate coralline habitats. Gochfeld et al. (2012) found that diseased sponges hosted significantly different bacterial assemblages compared to healthy sponges, with diseased sponges also exhibiting a significant decline in sponge mass and protein content. Sponge disease epidemics can have serious long-term effects on sponge populations, especially in long-lived, slow-growing species (Webster, 2007). Numerous sponge populations have been brought to the brink of extinction, including cases in the Caribbean (with 70-95% disappearance of sponge specimens) (Galstoff, 1942) and the Mediterranean (Vacelet, 1994; Gaino et al., 1992). Decaying patches and white bacterial film were reported in Haliclona oculata and Halichondria panicea in North Wales, 1988-89, however, no disease has been detected since (Webster, 2007). Specimens of Cliona spp. exhibited blackened damage since 2013 in Skomer. Preliminary results have shown that clean, fouled and blackened Cliona all have very different bacterial communities. The blackened Cliona are effectively dead and have a bacterial community similar to marine sediments. The fouled Cliona have a very distinct bacterial community that may suggest a specific pathogen caused the effect (Burton, pers comm; Preston & Burton, 2015). No record of diseases in the characterizing hydroids could be found. There appears to be little research into ascidian diseases, particularly in the Atlantic. The parasite Lankesteria ascidiae targets the digestive tubes and can cause ‘long faeces syndrome’ in Ciona intestinalis (although it has also been recorded in other species). Mortality occurs in severely affected individuals within about a week following first symptoms. (Mita et al., 2012). Sensitivity assessment. Whereas evidence for disease in corallines, ascidians and sponges exists, there is little evidence of mortality in the characterizing species in the British Isles. However, given evidence of limited mortality of Halichondria panicea, resistance is assessed as ‘Medium’, resilience as ‘High’ and sensitivity as ‘Low’. | MediumHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Removal of target species [Show more]Removal of target speciesBenchmark. Removal of species targeted by fishery, shellfishery or harvesting at a commercial or recreational scale. Further detail EvidenceDirect, physical impacts from harvesting are assessed through the abrasion and penetration of the seabed pressures. The sensitivity assessment for this pressure considers any biological/ecological effects resulting from the removal of target species on this biotope. It should be noted that Mytilus edulis and whelks may be found in this biotope and whilst abundance is likely to be low, harvesting cannot be ruled out. As these species are not characterizing, they are not considered for this pressure. No characterizing species are likely to be subject to targetted harvesting or collection. Therefore, this pressure is assessed as 'Not relevant'. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Removal of non-target species [Show more]Removal of non-target speciesBenchmark. Removal of features or incidental non-targeted catch (by-catch) through targeted fishery, shellfishery or harvesting at a commercial or recreational scale. Further detail EvidenceThe characteristic species probably compete for space within the biotope, so that loss of one species would probably have little if any effect on the other members of the community. However, removal of the characterizing species due to trampling or similar pressures is likely to remove a proportion of the biotope. These direct, physical impacts are assessed through abrasion pressures. The sensitivity assessment for this pressure considers any biological/ecological effects resulting from the removal of non-target species on this biotope. Therefore, incidental removal of the characterizing species could result in a decline of the biotope. Resistance is assessed as ‘Low’, resilience ‘High’ and sensitivity is ‘Low’. | LowHelp | HighHelp | LowHelp |

Introduction or spread of invasive non-indigenous species (INIS) Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |