Dead man's fingers (Alcyonium digitatum)

Distribution data supplied by the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS). To interrogate UK data visit the NBN Atlas.Map Help

| Researched by | Georgina Budd | Refereed by | Dr Richard G. Hartnoll |

| Authority | Linnaeus, 1758 | ||

| Other common names | - | Synonyms | - |

Summary

Description

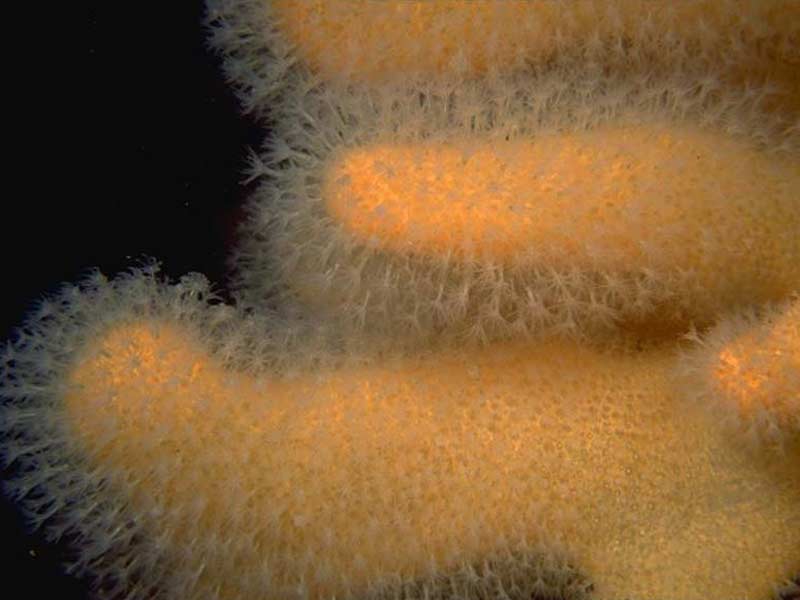

Mature colonies form thick, fleshy masses of irregular shape, typically of stout, finger-like lobes that usually exceed 20 mm in diameter. Young, developing colonies form encrustations about 5 -10mm thick. The height and breadth of colonies are up to 200 mm. Colonies are white or orange in colour, but may appear reddish or brownish during periods of inactivity when the polyps are withdrawn into the colony, owing to the development of a film of epibiota.

Recorded distribution in Britain and Ireland

Found on all British and Irish coasts.Global distribution

Alcyonium digitatum is recorded along the Atlantic Coasts of Europe from Portugal to Norway, in Iceland.Habitat

Attached to rocks, shells and stones where the otherwise dominant algae are inhibited by a lack of light and occasionally on living crabs and gastropods. Generally found in situations where strong water movement prevails. Occasionally on the lower shore but more common sublittorally, down to about 50 m.Depth range

Low water (springs) to 50 mIdentifying features

- White, yellow, orange or brownish in colour.

- Colonies form erect fleshy masses of stout, finger-like lobes.

- Polyps monomorphic, secondary polyps arising from solenia within the coenenchyme.

- Sclerites abundant in surface layer of coenenchyme, forming a crust.

- Anthocodia translucent white.

- Cross-sections of fingers have few cavities, usually less than 12.

- Found in areas of strong water movement, unlike Alcyonium glomeratum which prefers sheltered sites.

Additional information

May be confused with Alcyonium glomeratum, which prefers sites sheltered from wave action or tidal streams. It is blood red or rust coloured (occasionally pale orange or yellowish), has relatively slender branches, and a softer, more flaccid texture but a rough surface. In Alcyonium glomeratum the colonies are also more contractile, and cross sections through the fingers show numerous cavities.

Listed by

- none -

Biology review

Taxonomy

| Level | Scientific name | Common name |

|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Cnidaria | Sea anemones, corals, sea firs & jellyfish |

| Class | Anthozoa | Sea anemones, soft & cup corals, sea pens & sea pansies |

| Order | Malacalcyonacea | |

| Family | Alcyoniidae | |

| Genus | Alcyonium | |

| Authority | Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Recent Synonyms | ||

Biology

| Parameter | Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical abundance | Low density | ||

| Male size range | < 200 (height)mm | ||

| Male size at maturity | |||

| Female size range | Medium(11-20 cm) | ||

| Female size at maturity | |||

| Growth form | Digitate | ||

| Growth rate | Data deficient | ||

| Body flexibility | Low (10-45 degrees) | ||

| Mobility | |||

| Characteristic feeding method | Active suspension feeder, Non-feeding | ||

| Diet/food source | |||

| Typically feeds on | Phytoplankton & zooplankton | ||

| Sociability | |||

| Environmental position | Epifaunal | ||

| Dependency | Independent. | ||

| Supports | Host Enalcyonium forbesi and Enalcyonium rubicundum, the amphipod Jassa falcata, and layers of epibiota. Prey for Xandarovula patula and Tritonia hombergi. | ||

| Is the species harmful? | No | ||

Biology information

Cycles of activity

Alcyonium digitatum normally spends part of each day with its polyps expanded, during which time the colony is actively feeding, and part of the day contracted when the tentacles and columns of the polyps are withdrawn into the body of the colony (Hartnoll, 1975). The diurnal periodicity was studied by Ceccatty et al., (1963) in tideless conditions, who observed three to five periods of expansion every 24 hours, with no co-ordination between colonies. In contrast, Hickson (1892; 1895) observed a marked tidal rhythm of expansion and contraction in colonies within Plymouth Sound.

From February through to July all colonies expand and feed regularly. However, from late July through to December the colonies of Alcyonium digitatum remain contracted, during which time they do not feed and assume a shrunken appearance with a reddish or brownish colour. The change of colour is a result of the periods of inactivity as the surface of the colonies becomes covered with a layer of epibiota (diatoms and prostrate thalloid and filamentous algae initially, from which arises a forest of erect algae and hydroids). The amphipod Jassa falcata also builds its mucous and detritus tubes amongst the other epibiota, adding to and consolidating the covering (Hartnoll, 1975). Once the colonies recommence expansion in December the epibenthic film is sloughed off. The season of prolonged inactivity coincides with the final months of gonad maturation and the shedding of the epibenthic film immediately precedes the spawning of the gametes (see reproduction) (Hartnoll, 1975; 1977)

Feeding

Roushdy & Hansen (1961) demonstrated filtration of phytoplankton by Alcyonium digitatum using radiolabelled algae. In Alcyonium digitatum the current maintained in and out of the polyps by ciliary action not only conveys oxygen but also constantly brings a supply of food into reach (Hickson, 1901).

Chemical defences

Mackie (1987) reported that methanol extracts of the octocorals Alcyonium digitatum and Pennatula phosphorea contained substances that deterred feeding in the Dover sole, Solea solea.

Anatomy

Hickson (1895) describes the microscopic structure of Alcyonium digitatum.

Habitat preferences

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Physiographic preferences | Open coast, Offshore seabed |

| Biological zone preferences | Circalittoral offshore, Lower circalittoral, Upper circalittoral |

| Substratum / habitat preferences | Artificial (man-made), Bedrock, Caves, Cobbles, Large to very large boulders, Overhangs, Small boulders |

| Tidal strength preferences | Moderately strong 1 to 3 knots (0.5-1.5 m/sec.), Strong 3 to 6 knots (1.5-3 m/sec.) |

| Wave exposure preferences | Exposed, Moderately exposed, Sheltered, Very exposed, Very sheltered |

| Salinity preferences | Full (30-40 psu), Variable (18-40 psu) |

| Depth range | Low water (springs) to 50 m |

| Other preferences | Alcyonium digitatum prefers slopes of different gradient at different depths. Around the Isle of Man, Alcyonium digitatum prefers overhangs down to 10 m, from 10-20 m it extends onto vertical slopes, whilst below 20 m it is also found on gentle slopes and horizontal hard surfaces (Hartnoll, 1975). |

| Migration Pattern | Non-migratory or resident |

Habitat Information

- Alcyonium digitatum prefers areas of strong water movement resulting from wave turbulence or currents.

- Records of Alcyonium digitatum from New England, USA have been shown to be Alcyonium siderium Verrill, which differs in both morphology and reproduction and lacks the seasonal quiescent phase (Sebens, 1983; Hartnoll pers. comm.).

Life history

Adult characteristics

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Reproductive type | Gonochoristic (dioecious) |

| Reproductive frequency | Annual episodic |

| Fecundity (number of eggs) | 10,000-100,000 |

| Generation time | 1-2 years |

| Age at maturity | 2 or 3 years old |

| Season | December - January |

| Life span | See additional information |

Larval characteristics

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Larval/propagule type | - |

| Larval/juvenile development | Lecithotrophic |

| Duration of larval stage | See additional information |

| Larval dispersal potential | Greater than 10 km |

| Larval settlement period | January to February |

Life history information

Lifespan

Evidence suggests that Alcyonium digitatum has an extensive lifespan. Observations of marked colonies showed that colonies 10-15 cm in height were between 5 and 10 years old (Hartnoll, unpublished). The lifespan certainly exceeds 20 years as colonies have been followed for 28 years in marked plots (Lundälv, pers. Comm., in Hartnoll, 1998).

Sex ratio

The majority of colonies are either male or female, < 1% are hermaphroditic and these have both apparently functional ova and testes which may develop within the same polyp (Hartnoll, 1977). The soft coral genus Alcyonium is among the most reproductively diverse invertebrate taxa known. The genus includes species that vary both in mode of reproduction and sexual expression (McFadden, 2000).

Sexual maturity

The development of the gametes takes 12 months, so the earliest onset of sexual maturity can only be in the second year, at which point the smallest of colonies have usually attained a wet weight of 1g. However, in some colonies, maturity is delayed until the third or subsequent year, by which time the colony may have attained a wet weight of 20 g (Hartnoll, 1975; 1977).

Gamete maturation

The annual reproductive cycle commences when the gametes begin to develop during December and January; the testes have a diameter of 0.05 mm and the ova 0.15 mm at this stage. The ova steadily increase in size and exceed 0.5 mm in diameter by July / August, and reach a final diameter of 0.6 mm in October, which is retained until spawning in December. The mature ova are bright orange in colour owing to their heavy yolk content. Growth of the testes is less regular. The onset of growth occurs in May when they rapidly increase in size and are opaque white in appearance. A second period of slow growth occurs from August to December (Hartnoll, 1975). In both sexes, the gonads develop on the edges of the mesenteries (partitions that divide the coelenteron) and lie within the gastric cavity, attached to the mesentery, until spawning occurs. The maturing gonads occlude the gastric cavity of the polyps and it is postulated that the quiescent period in the annual cycle of activity of Alcyonium digitatum is caused by the inability to feed, however, the same seasonal cessation of activity occurs in a proportion of sexually immature colonies. White colonies of Alcyonium digitatum were reported to spawn slightly earlier than orange colonies and this may favour a degree of sexual isolation between the two colour morphs (Hartnoll, 1975).

Spawning

Alcyonium digitatum spawns during December and January. Gametes are released into the water and fertilization occurs externally. The embryos are neutrally buoyant and float freely for 7 days. The embryos give rise to actively swimming lecithotrophic planulae which may have an extended pelagic life (See below) before they eventually settle (usually within one or two further days) and metamorphose to polyps (Matthews, 1917; Hartnoll, 1975).

Survival in the pelagic zone

In laboratory experiments, several larvae of Alcyonium digitatum failed to settle within 10 days, presumably finding the conditions unsuitable, these larvae proved to be able to survive 35 weeks as non-feeding planulae. After 14 weeks some were still swimming and after 24 weeks the surface ciliation was still active although they rested on the bottom of the tanks, by the end of the experiment at 35 weeks the larvae had shrunk to a diameter of 0.3 mm. This ability to survive for long periods in the plankton may favour the dispersal and eventual discovery of a site suitable for settlement (Hartnoll, 1975).

Advantages of mid-winter spawning

The combination of spawning in winter and the long pelagic lifespan may allow a considerable length of time for the planulae to disperse, settle and metamorphose ahead of the spring plankton bloom. Young Alcyonium digitatum will consequently be able to take advantage of an abundant food resource in spring and be well developed before the appearance of other forms that may otherwise compete for the same substrata. In addition, because the planulae do not feed whilst in the pelagic zone they do not suffer by being released at the time of minimum plankton density and they may also benefit from the scarcity of predatory zooplankton which would otherwise feed upon them (Hartnoll, 1975).

Sensitivity review

The MarLIN sensitivity assessment approach used below has been superseded by the MarESA (Marine Evidence-based Sensitivity Assessment) approach (see menu). The MarLIN approach was used for assessments from 1999-2010. The MarESA approach reflects the recent conservation imperatives and terminology and is used for sensitivity assessments from 2014 onwards.

Physical pressures

Use / to open/close text displayed

| Intolerance | Recoverability | Sensitivity | Evidence / Confidence | |

Substratum loss [Show more]Substratum lossBenchmark. All of the substratum occupied by the species or biotope under consideration is removed. A single event is assumed for sensitivity assessment. Once the activity or event has stopped (or between regular events) suitable substratum remains or is deposited. Species or community recovery assumes that the substratum within the habitat preferences of the original species or community is present. Further details EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum is permanently attached to rocky substratum. Removal of the substratum would also remove this species within the area under consideration and mortality is judged to be high. | High | High | Moderate | Moderate |

Smothering [Show more]SmotheringBenchmark. All of the population of a species or an area of a biotope is smothered by sediment to a depth of 5 cm above the substratum for one month. Impermeable materials, such as concrete, oil, or tar, are likely to have a greater effect. Further details. EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum is permanently attached to the surface of rocky substrata. Thus it would be unable to avoid the deposition of a smothering layer of material up to a depth of 5 cm. Some colonies can attain a height of up to 20 cm so would still be able to expand tentacles and columns of the polyps to filter feed, and materials may be sloughed off with a large amount of mucous (see siltation). Smaller / younger colonies that initially form encrustation's between 5 and 10 mm thick are likely to be killed by smothering as respiration is likely to be hindered and an intolerance of intermediate is recorded. | Intermediate | High | Low | Low |

Increase in suspended sediment [Show more]Increase in suspended sedimentBenchmark. An arbitrary short-term, acute change in background suspended sediment concentration e.g., a change of 100 mg/l for one month. The resultant light attenuation effects are addressed under turbidity, and the effects of rapid settling out of suspended sediment are addressed under smothering. Further details EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum has been shown to be tolerant of high levels of suspended sediment. Hill et al. (1997) demonstrated that Alcyonium digitatum sloughed off settled particles with a large amount of mucous (see adult biology, additional information). Siltation is normally only a problem in sheltered areas, and the slope of the rock is also important as little silt will settle on vertical surfaces and overhangs (Hiscock & Hoare, 1973) where Alcyonium digitatum is found. | Low | Very high | Very Low | Moderate |

Decrease in suspended sediment [Show more]Decrease in suspended sedimentBenchmark. An arbitrary short-term, acute change in background suspended sediment concentration e.g., a change of 100 mg/l for one month. The resultant light attenuation effects are addressed under turbidity, and the effects of rapid settling out of suspended sediment are addressed under smothering. Further details Evidence | No information | |||

Desiccation [Show more]Desiccation

EvidenceThe population of Alcyonium digitatum is predominantly subtidal so the factor is judged not relevant. However, a few specimens of Alcyonium digitatum may be found on the lower shore, attached to rocks where the otherwise dominant algae are inhibited by a lack of light, such as under overhangs and in crevices. Although their location may offer some protection form sunlight and a drying wind, these specimens are likely to be highly intolerant of desiccation as Alcyonium digitatum has a large surface area to volume ratio and turgid body form. | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant | Moderate |

Increase in emergence regime [Show more]Increase in emergence regimeBenchmark. A one hour change in the time covered or not covered by the sea for a period of one year. Further details EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum is predominantly a subtidal species so the factor is judged not relevant. A change in emergence regime will only effect a small proportion of specimens found on the lower shore where it favours locations under overhangs and in crevices where otherwise dominant algae are inhibited by a lack of light. Thus to some extent its position on the substrata may protect this species from the desiccating factors of air and direct sunlight. Alcyonium digitatum has a large surface area to volume ratio, and a turgid body form which would make it prone to mortality caused by desiccation following a change in emergence and a longer exposure to air and direct sunlight. | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant | Moderate |

Decrease in emergence regime [Show more]Decrease in emergence regimeBenchmark. A one hour change in the time covered or not covered by the sea for a period of one year. Further details Evidence | No information | |||

Increase in water flow rate [Show more]Increase in water flow rateA change of two categories in water flow rate (view glossary) for 1 year, for example, from moderately strong (1-3 knots) to very weak (negligible). Further details EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum is a suspension feeder relying on water currents to supply food. It therefore thrives in conditions of vigorous water flow e.g. around Orkney and St Abbs (Scotland), where it may experience tidal currents of 3 and 4 knots during spring tides (Kluijver, 1993). | Tolerant* | Not relevant | Not sensitive* | Moderate |

Decrease in water flow rate [Show more]Decrease in water flow rateA change of two categories in water flow rate (view glossary) for 1 year, for example, from moderately strong (1-3 knots) to very weak (negligible). Further details EvidenceA decreased water flow rate may impact upon Alcyonium digitatum in that feeding efficiency could decrease as less material (phytoplankton & zooplankton) would be brought into contact with the colonies. Also a lower energy environment favours siltation and although Alcyonium digitatum has been found to tolerate a high level of suspended sediment, the energetic cost of producing enough mucous to slough off deposited material may reduce the species viability and an intermediate intolerance is recorded. Recoverability, see additional information below. | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Increase in temperature [Show more]Increase in temperature

For intertidal species or communities, the range of temperatures includes the air temperature regime for that species or community. Further details EvidenceThe geographic range of Alcyonium digitatum from Iceland in the North, to Portugal in the South illustrates that the species is tolerant of a range of temperatures and it is unlikely that this species will be adversely affected by a long term temperature change in British waters. | Low | High | Low | Moderate |

Decrease in temperature [Show more]Decrease in temperature

For intertidal species or communities, the range of temperatures includes the air temperature regime for that species or community. Further details EvidenceThe geographic range of Alcyonium digitatum from Iceland in the North, to Portugal in the South illustrates that the species is tolerant of a range of temperatures and it is unlikely that this species will be adversely affected by a long term temperature change in British waters. Alcyonium digitatum was also reported to be apparently unaffected by the severe winter of 1962-1963 (Crisp, 1964). | Low | High | Low | Moderate |

Increase in turbidity [Show more]Increase in turbidity

EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum filter feeds on both phytoplankton and zooplankton. Increased turbidity that reduces the amount of light available for primary production by phytoplankton for a period of one month may impact upon the food resource available to Alcyonium digitatum. The effect of a change in turbidity and hence food resources is likely to be greater between February and July (when the colony is active) rather than between August and December when the colony is inactive. An intolerance of low is recorded as the species would only be suffering from a short term sub-lethal effect. However, Alcyonium digitatum may benefit indirectly from increased turbidity as decreased light penetration may cause the decline of algal species making new substrata available for larval settlement. Recoverability, see additional information below. | Low | Very high | Very Low | Moderate |

Decrease in turbidity [Show more]Decrease in turbidity

Evidence | No information | |||

Increase in wave exposure [Show more]Increase in wave exposureA change of two ranks on the wave exposure scale (view glossary) e.g., from Exposed to Extremely exposed for a period of one year. Further details EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum is tolerant of very strong wave action and is unlikely to be adversely affected by increased wave exposure. | Tolerant | Not relevant | Not sensitive | Moderate |

Decrease in wave exposure [Show more]Decrease in wave exposureA change of two ranks on the wave exposure scale (view glossary) e.g., from Exposed to Extremely exposed for a period of one year. Further details EvidenceIn the absence of moderate or strong tidal streams, a decrease in wave action is likely to have an adverse effect on Alcyonium digitatum as food supplies will be reduced and siltation may occur (see siltation and water flow). Recoverability, see additional information below. | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Noise [Show more]Noise

EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum does not have the ability to perceive noise. | Tolerant | Not relevant | Not sensitive | Not relevant |

Visual presence [Show more]Visual presenceBenchmark. The continuous presence for one month of moving objects not naturally found in the marine environment (e.g., boats, machinery, and humans) within the visual envelope of the species or community under consideration. Further details EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum does not have the ability to detect the visual presence of objects. | Tolerant | Not relevant | Not sensitive | Not relevant |

Abrasion & physical disturbance [Show more]Abrasion & physical disturbanceBenchmark. Force equivalent to a standard scallop dredge landing on or being dragged across the organism. A single event is assumed for assessment. This factor includes mechanical interference, crushing, physical blows against, or rubbing and erosion of the organism or habitat of interest. Where trampling is relevant, the evidence and trampling intensity will be reported in the rationale. Further details. EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum is prone to damage and abrasion by fishing gears e.g. rock hopper otter trawls and Newhaven scallop dredges that are designed to penetrate the sea bed (Hartnoll, 1998). In addition, the anchoring of boats for purposes of recreational diving may cause cumulative damage in heavily visited sites. Magorrian & Service (1998) reported that trawling for queen scallops resulted in removal of emergent epifauna and damage to horse mussel beds in in Strangford Lough. They suggested that the emergent epifauna such as Alcyonium digitatum were more intolerant than the horse mussels themselves and reflected early signs of damage (Service & Magorrian, 1997; Magorrian & Service, 1998; Service 1998). Veale et al., 2000 reported that the abundance, biomass and production of epifaunal assemblages, including Alcyonium digitatum, decreased with increasing fishing effort. An intolerance rank of intermediate is recorded as it is likely that the proportion of the population on vertical slopes and under overhangs will be unaffected by mechanical abrasion. The population inhabiting horizontal surfaces at greater depths are at risk from abrasion. However, the fact that Alcyonium digitatum is more abundant on high fishing effort grounds suggests that this seemingly fragile species is more resistant to abrasive disturbance than might be assumed (Bradshaw et al., 2000), presumably owing to the ability for the replacement of senescent cells and regeneration of damaged tissue in addition to the early larval colonization of available substrata. Recoverability, see additional information below. | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Displacement [Show more]DisplacementBenchmark. Removal of the organism from the substratum and displacement from its original position onto a suitable substratum. A single event is assumed for assessment. Further details EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum is likely to be highly intolerant of displacement. The species is permanently attached to the substratum and once displaced does not have the ability to re-establish its attachment. Recoverability, see additional information below. | High | High | Moderate | Low |

Chemical pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Intolerance | Recoverability | Sensitivity | Evidence / Confidence | |

Synthetic compound contamination [Show more]Synthetic compound contaminationSensitivity is assessed against the available evidence for the effects of contaminants on the species (or closely related species at low confidence) or community of interest. For example:

The evidence used is stated in the rationale. Where the assessment can be based on a known activity then this is stated. The tolerance to contaminants of species of interest will be included in the rationale when available; together with relevant supporting material. Further details. EvidenceSmith (1968) reported dead colonies of Alcyonium digitatum at a depth of 16 m in the locality of Sennen Cove (Pedu-men-du, Cornwall) resulting from the offshore spread and toxic effect of detergents (a mixture of a surfactant and an organic solvent) e.g. BP 1002 sprayed along the shoreline to disperse oil from the Torrey Canyon tanker spill. Possible sub-lethal effects of exposure to synthetic chemicals, may result in a change in morphology, growth rate or disruption of reproductive cycle. The vulnerability of this species to concentrations of pollutants may also depend on variations in other factors e.g. temperature and salinity conditions outside the normal range. However, no additional information concerning the direct biological effects of synthetic compound contamination on Alcyonium digitatum has been found to comment further. | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Heavy metal contamination [Show more]Heavy metal contaminationEvidencePossible sub-lethal effects of exposure to heavy metals, may result in a change in morphology, growth rate or disruption of reproductive cycle. The vulnerability of this species to concentrations of pollutants may also depend on variations in other factors e.g. temperature and salinity conditions outside the normal range. However, no information on the direct biological effects of heavy metal contamination on Alcyonium digitatum has been found to comment further. | No information | No information | No information | Not relevant |

Hydrocarbon contamination [Show more]Hydrocarbon contaminationEvidenceThe vast proportion of the population of Alcyonium digitatum is permanently subtidal and because oil pollution is mainly a surface phenomenon its impact upon circalittoral turf communities is likely to be limited (Hartnoll, 1998). In addition Alcyonium digitatum is able to retract its colonies and slough off material from its surface so may be able to tolerate a light oiling. However, Smith (1968) reported dead colonies of Alcyonium digitatum at a depth of 16m in the locality of Sennen Cove (Pedu-men-du, Cornwall) resulting from the offshore spread and toxic effect of detergents sprayed along the shoreline to disperse oil from the Torrey Cannon tanker spill (see synthetic chemicals). | Low | High | Low | Very low |

Radionuclide contamination [Show more]Radionuclide contaminationEvidenceThere is insufficient information available to comment on the biological effects of radionuclide contamination on Alcyonium digitatum. | No information | No information | No information | Not relevant |

Changes in nutrient levels [Show more]Changes in nutrient levelsEvidenceAlcyonium digitatum is a passive suspension feeder on phytoplankton and zooplankton. Nutrient enrichment of coastal waters (eutrophication) that enhances the population of phytoplankton may be beneficial to Alcyonium digitatum in terms of an increased food supply but the effects are uncertain (Hartnoll, 1998). However, the survival of Alcyonium digitatum may be influenced indirectly. High primary productivity in the water column combined with high summer temperature and the development of thermal stratification (which prevents mixing of the water column) can lead to hypoxia of the bottom waters and Alcyonium digitatum is likely to be highly intolerant of periods of hypoxia (see oxygenation). | Low | High | Low | Very low |

Increase in salinity [Show more]Increase in salinity

EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum does inhabit situations such as the entrances to sea lochs where low salinity may occasionally occur. However, its distribution and the depth at which it occurs suggest that Alcyonium digitatum is unlikely to survive significant dilution. | Intermediate | High | Low | Very low |

Decrease in salinity [Show more]Decrease in salinity

Evidence | No information | |||

Changes in oxygenation [Show more]Changes in oxygenationBenchmark. Exposure to a dissolved oxygen concentration of 2 mg/l for one week. Further details. EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum mainly inhabits environments in which the oxygen concentration usually exceeds 5 ml l-1 and respiration is aerobic. Assimilation of oxygen occurs simply by diffusion through the epidermis of exposed tissues and transport to tissues is facilitated by hydroplasmic flow and ciliary activity (Hickson, 1901). It is likely that Alcyonium digitatum would be highly intolerant of a period of hypoxia so an intolerance assessment of high is recorded. Recoverability, see additional information below. | High | High | Moderate | Very low |

Biological pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Intolerance | Recoverability | Sensitivity | Evidence / Confidence | |

Introduction of microbial pathogens/parasites [Show more]Introduction of microbial pathogens/parasitesBenchmark. Sensitivity can only be assessed relative to a known, named disease, likely to cause partial loss of a species population or community. Further details. EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum acts as the host for the endoparasitic species Enalcyonium forbesiand Enalcyonium rubicundum (Stock, 1988). Parasitisation may reduce the viability of a colony but not to the extent of killing them but no further evidence was found to substantiate this suggestion. | No information | No information | No information | Not relevant |

Introduction of non-native species [Show more]Introduction of non-native speciesSensitivity assessed against the likely effect of the introduction of alien or non-native species in Britain or Ireland. Further details. EvidenceInsufficient | No information | No information | No information | Not relevant |

Extraction of this species [Show more]Extraction of this speciesBenchmark. Extraction removes 50% of the species or community from the area under consideration. Sensitivity will be assessed as 'intermediate'. The habitat remains intact or recovers rapidly. Any effects of the extraction process on the habitat itself are addressed under other factors, e.g. displacement, abrasion and physical disturbance, and substratum loss. Further details. EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum is not a commercially exploited species. | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant |

Extraction of other species [Show more]Extraction of other speciesBenchmark. A species that is a required host or prey for the species under consideration (and assuming that no alternative host exists) or a keystone species in a biotope is removed. Any effects of the extraction process on the habitat itself are addressed under other factors, e.g. displacement, abrasion and physical disturbance, and substratum loss. Further details. EvidenceAlcyonium digitatum is a sedentary species that might be expected to suffer from the effects of dredging. However it has been found present in great abundance on some high-effort scallop dredging grounds around the Isle of Man, Irish Sea (Bradshaw et al., 2000) (see also adult abrasion and physical disturbance). Hill et al., (1997) demonstrated that Alcyonium digitatum is tolerant of high levels of suspended sediment (that may be generated by dredging) as it sloughs off settled particles with a large amount of mucous. This mechanism may help Alcyonium digitatum survive in heavily disturbed areas and this seemingly fragile species is evidently more resistant to disturbance than might be assumed. An intolerance rank of intermediate is recorded as it is likely that the proportion of the population on vertical slopes and under overhangs will be unaffected by mechanical abrasion caused by equipment used to catch other species, whereas the population inhabiting horizontal surfaces at greater depths is at risk from abrasion. Recoverability, see additional information below. | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Additional information

Recoverability. It is likely that Alcyonium digitatum has a high recovery potential. Its reproductive strategy is to 'broadcast' gametes into the water for fertilization indicating that fecundity is high. The combination of spawning in winter and that the larvae may have a long pelagic life allows a considerable length of time for the planulae to disperse (recruits from other populations can replace impacted populations), settle and metamorphose ahead of the spring plankton bloom. Young Alcyonium digitatum will consequently be able to take advantage of an abundant food resource in spring and be well developed before the appearance of other forms which may compete for the same substrata. In addition, because the planulae do not feed whilst in the pelagic zone they do not suffer by being released at the time of minimum plankton density. They may also benefit from the scarcity of predatory zooplankton which would otherwise prey upon them (Hartnoll, 1975).

Importance review

Policy/legislation

- no data -

Status

| National (GB) importance | - | Global red list (IUCN) category | - |

Non-native

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Native | - |

| Origin | - |

| Date Arrived | - |

Importance information

Biofouling. Alcyonium digitatum is often a predominant member of macrofouling assemblages on offshore structures (Sell, 1992). Along with other species in a biofouling assemblage, its presence increases drag and accelerates corrosion (Pipe, 1981).

Food source. The nudibranchTritonia hombergii feeds exclusively on Alcyonium digitatum (Allmon & Sebens, 1998; Picton & Morrow, 1994).

Provision of substratum. From late July through to December the colonies of Alcyonium digitatum remain contracted, during which time they do not feed and assume a shrunken appearance with an obvious reddish or brownish colour. As a result of this period of inactivity the surface of the colonies becomes covered with a layer of epibiota; diatoms and prostrate thalloid and filamentous algae initially, from which arises a forest of erect algae and hydroids. The amphipod Jassa falcata also builds its mucous and detritus tubes amongst the other epibiota, adding to and consolidating the covering (Hartnoll, 1975).

Role in organic cycles. Migné et al. (1996) conducted a biometric study on Alcyonium digitatum with the aim of relating both the carbon and the nitrogen content of this species to a simple and rapid measurement. It appeared useful to express the biomass of this species in terms of carbon or nitrogen and then to consider dynamic processes such as respiration or excretion as fluxes of carbon and nitrogen. Converting biomass into a more fundamental measurement of living matter such as carbon or nitrogen content should enable understanding and quantification of the species' role in carbon and nitrogen cycles. For instance, the bottom of the Dover Strait (eastern English Channel) is dominated by suspension feeders (Davoult, 1990) that probably play a leading role in the exchange of organic matter at the bottom boundary layer (Migné et al., 1996). Three species, including Alcyonium digitatum, accounted for 97% of the total biomass of the suspension-feeding community studied in the English Channel (Migné & Davoult, 1995 b).

Bibliography

Allmon, R.A. & Sebens, K.P., 1988. Feeding biology and ecological impact of an introduced nudibranch Tritonia plebia, New England, USA. Marine Biology, 99, 375-385.

Bradshaw, C., Veale, L.O., Hill, A.S. & Brand, A.R., 2000. The effects of scallop dredging on gravelly seabed communities. In: Effects of fishing on non-target species and habitats (ed. M.J. Kaiser & de S.J. Groot), pp. 83-104. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Ceccatty, M.P., Buisson, B. & Gargouil, Y. M., 1963. Rhythmes naturels et réactions motrices chez Alcyonium digitatum Linn. Et Veretillum cynomorium Cuv. Compte rendu des Séances de la Societé de Biologie, 157, 616-618.

Crisp, D.J. (ed.), 1964. The effects of the severe winter of 1962-63 on marine life in Britain. Journal of Animal Ecology, 33, 165-210.

Davoult, D., 1990. Biofaciès et structure trophique du peuplement des cailloutis du Pas de Calais (France). Océanologica Acta, 13, 335-348.

De Kluijver, M.J., 1993. Sublittoral hard-substratum communities off Orkney and St Abbs (Scotland). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 73 (4), 733-754.

Gili, J-M. & Hughes, R.G., 1995. The ecology of marine benthic hydroids. Oceanography and Marine Biology: an Annual Review, 33, 351-426.

Graham, A., 1988. Molluscs: prosobranchs and pyramellid gastropods (2nd ed.). Leiden: E.J. Brill/Dr W. Backhuys. [Synopses of the British Fauna No. 2]

Hartnoll, R.G., 1975. The annual cycle of Alcyonium digitatum. Estuarine and Coastal Marine Science, 3, 71-78.

Hartnoll, R.G., 1977. Reproductive strategy in two British species of Alcyonium. In Biology of benthic organisms, (ed. B.F. Keegan, P.O Ceidigh & P.J.S. Boaden), pp. 321-328. New York: Pergamon Press.

Hartnoll, R.G., 1998. Circalittoral faunal turf biotopes: an overview of dynamics and sensitivity characteristics for conservation management of marine SACs, Volume VIII. Scottish Association of Marine Sciences, Oban, Scotland, 109 pp. [UK Marine SAC Project. Natura 2000 reports.] Available from: http://ukmpa.marinebiodiversity.org/uk_sacs/pdfs/circfaun.pdf

Hayward, P.J. & Ryland, J.S. (ed.) 1995b. Handbook of the marine fauna of North-West Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hickman, C.S., 1992. Reproduction and development of trochean gastropods. Veliger, 35, 245-272.

Hickson, J.S., 1901. Liverpool Marine Biological Committee Memoirs Number V. Alcyonium. Proceedings and Transactions of the Liverpool Biological Society, 15, 92-113.

Hickson, S.J., 1892. Some preliminary notes on the anatomy and habits of Alcyonium digitatum. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 7, 305-308

Hickson, S.J., 1895. The anatomy of Alcyonium digitatum. Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, 37, 343-388.

Hill, A.S., Brand, A.R., Veale, L.O. & Hawkins, S.J., 1997. Assessment of the effects of scallop dredging on benthic communities. Final Report to MAFF, Contract CSA 2332, Liverpool: University of Liverpool

Hiscock, H., 1985b. Aspects of the ecology of rocky sublittoral areas. In The Ecology of Rocky Coasts: essays presented to J.R. Lewis, D.Sc. (ed. P.G. Moore & R. Seed), pp. 290-328. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd.

Hiscock, K., 1983. Water movement. In Sublittoral ecology. The ecology of shallow sublittoral benthos (ed. R. Earll & D.G. Erwin), pp. 58-96. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Howson, C.M. & Picton, B.E., 1997. The species directory of the marine fauna and flora of the British Isles and surrounding seas. Belfast: Ulster Museum. [Ulster Museum publication, no. 276.]

Kaiser, M.J., Ramsay, K., Richardson, C.A., Spence, F.E. & Brand, A.R., 2000. Chronic fishing disturbance has changed shelf sea benthic community structure. Journal of Animal Ecology, 69, 494-503.

Mackie, A.M., 1987. Preliminary studies on the chemical defences of the British octocorals Alcyonium digitatum and Pennatula phosphorea. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, 86A, 629-632

Manuel, R.L., 1988. British Anthozoa. Synopses of the British Fauna (New Series) (ed. D.M. Kermack & R.S.K. Barnes). The Linnean Society of London [Synopses of the British Fauna No. 18.]. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/iroh.19810660505

Marchetti, R., 1992. The problems of the Emalia Romagna coastal waters: facts and interpretations. Science of the Total Environment, Supplement 1992, 21-33.

Matthews, A., 1917. The development of Alcyonium digitatum with some notes on early colony formation. Quarterly Journal of Microscopial Science, 62, 43-94.

McFadden, C.S., Donahue, R., Hadland, B.K. & Weston, R., 2000. A molecular phylogenetic analysis of reproductive trait evolution in the soft coral genus Alcyonium. Evolution, 55, 54-67.

Migné, A. & Davoult, D., 1995b. Multi-scale heterogeneity in a macrobenthic epifauna community. Hydrobiologia, 300/301, 375-381.

Migné, A., Davoult, D., Janquin, M.A. & Kupka, A., 1996. Biometrics, carbon and nitrogen content in two Cnidarians: Urticina felina and Alcyonium digitatum. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 76, 595-602.

Moore, J., 1995. The marine inlets of south west Britain: an overview. Report to the JNCC from the Field Studies Research Council., Field Studies Research Council.

Picton, B. E. & Morrow, C.C., 1994. A Field Guide to the Nudibranchs of the British Isles. London: Immel Publishing Ltd.

Pipe, A., 1981. North Sea fouling organisms and their potential effects on the corrosion of North Sea structures. London:

Riedl, R., 1971. Water movement, Animals. In Marine Ecology, Vol.1, Environmental factors, (ed. O. Kinne), pp. 1123-1149. New York: John Wiley.

Roushdy, H.M. & Hansen, V.K., 1961. Filtration of phytoplankton by the octocoral Alcyonium digitatum L. Nature, 190, 649-650.

Sebens, K.P., 1983. The larval and juvenile ecology of the temperate octocoral Alcyonium siderium Verril. I. Substratum selection by benthic larvae. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 71, 73-89.

Sell, D., 1992. Marine fouling. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Section B - Biological Sciences, 100, 169-184.

Smith, J.E. (ed.), 1968. 'Torrey Canyon'. Pollution and marine life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stock, J.H., 1988. Lamippidae (Copepoda : Siphonostomatoida) parasitic in Alcyonium. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 68 (2), 351-359.

Datasets

Centre for Environmental Data and Recording, 2018. Ulster Museum Marine Surveys of Northern Ireland Coastal Waters. Occurrence dataset https://www.nmni.com/CEDaR/CEDaR-Centre-for-Environmental-Data-and-Recording.aspx accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-09-25.

Cofnod – North Wales Environmental Information Service, 2018. Miscellaneous records held on the Cofnod database. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/hcgqsi accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-25.

Dorset Environmental Records Centre, 2018. Ross Coral Mapping Project - NBN South West Pilot Project Case Studies. Occurrence dataset:https://doi.org/10.15468/mnlzxc accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-25.

Environmental Records Information Centre North East, 2018. ERIC NE Combined dataset to 2017. Occurrence dataset: http://www.ericnortheast.org.ukl accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-09-38

Fenwick, 2018. Aphotomarine. Occurrence dataset http://www.aphotomarine.com/index.html Accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-10-01

Fife Nature Records Centre, 2018. St Andrews BioBlitz 2014. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/erweal accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-27.

Fife Nature Records Centre, 2018. St Andrews BioBlitz 2015. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/xtrbvy accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-27.

Fife Nature Records Centre, 2018. St Andrews BioBlitz 2016. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/146yiz accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-27.

Isle of Wight Local Records Centre, 2017. IOW Natural History & Archaeological Society Marine Invertebrate Records 1853- 2011. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/d9amhg accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-27.

Kent Wildlife Trust, 2018. Kent Wildlife Trust Shoresearch Intertidal Survey 2004 onwards. Occurrence dataset: https://www.kentwildlifetrust.org.uk/ accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-10-01.

Manx Biological Recording Partnership, 2022. Isle of Man historical wildlife records 1990 to 1994. Occurrence dataset:https://doi.org/10.15468/aru16v accessed via GBIF.org on 2024-09-27.

Merseyside BioBank., 2018. Merseyside BioBank Active Naturalists (unverified). Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/smzyqf accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

National Trust, 2017. National Trust Species Records. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/opc6g1 accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

NBN (National Biodiversity Network) Atlas. Available from: https://www.nbnatlas.org.

Norfolk Biodiversity Information Service, 2017. NBIS Records to December 2016. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/jca5lo accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

North East Scotland Biological Records Centre, 2017. NE Scotland other invertebrate records 1800-2010. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/ifjfxz accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

OBIS (Ocean Biodiversity Information System), 2025. Global map of species distribution using gridded data. Available from: Ocean Biogeographic Information System. www.iobis.org. Accessed: 2025-07-30

South East Wales Biodiversity Records Centre, 2018. Dr Mary Gillham Archive Project. Occurance dataset: http://www.sewbrec.org.uk/ accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-10-02

South East Wales Biodiversity Records Centre, 2023. SEWBReC Marine and other Aquatic Invertebrates (South East Wales). Occurrence dataset:https://doi.org/10.15468/zxy1n6 accessed via GBIF.org on 2024-09-27.

Citation

This review can be cited as:

Last Updated: 08/05/2008